On January 8, 2025, Marketing Brew published a report titled Peacock is testing mini-games and vertical videos to boost engagement. I am aware that Peacock is NBC-Universal’s video streaming service, but I have no experience with it. While I have no personal stake in the matter, the report’s description of NBC’s plans for the mini games left me nonplussed:

The test will include games called Daily Sort, Daily Swap, Predictions, What The, and Venn, some of which will be tied to Peacock programming. Through the games, users will be able to predict outcomes of shows, and they will be able to return later to the app to see if their predictions were right.

I watch anime on Crunchryoll and HiDive, which are both anime streaming services (I use the web UI in both cases instead of their proprietary apps). Never once have I thought that my anime viewing experience would be enriched by pop-up quizzes asking me to predict what happens next.

(Aside: I will concede pop-up anime quizzes could be fun if you solicited predictions from someone watching the School Days anime who has no prior knowledge of what happens.)

The reason why I am sharing this Marketing Brew report is not to opine on the specific topic of whether streaming apps can benefit from mini games. I am sharing it because of a specific, utterly horrifying, quote from Karen Kovacs, who is apparently NBCU’s “president of advertising and partnerships.” I re-print Ms. Kovacs quote as presented in the report below:

We’re adding gaming…and thinking very specifically about trying to create a very welcoming environment for Gen Z, so when the NBA comes next year, we’ve already got them in, we’ve got them engaged, and then we’re going to feed them content that we know they’re going to be really excited about

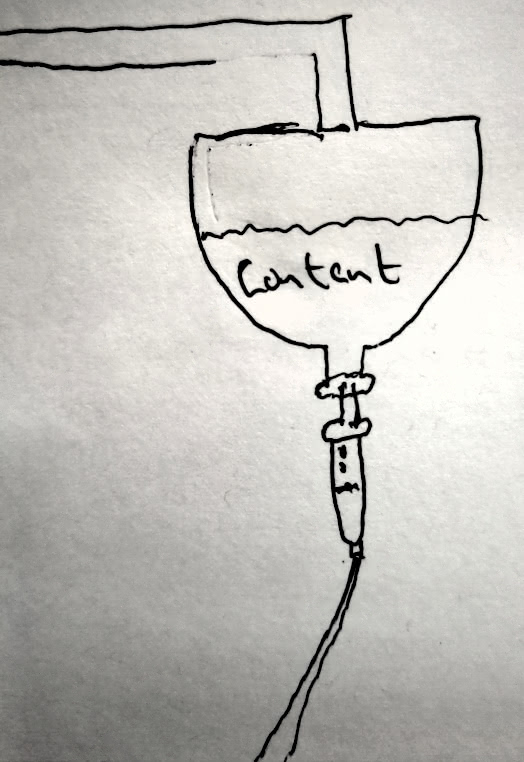

The best term I cam come up with to describe this quote is skin-crawling. Where does it all go wrong? I would start with we’ve got them engaged. Here she does not mean she is giving her customers a good service that they will want to pay for. She means that her service can use gimmicks to ensure that her customers keep their eyes on her app and advertising. But where it really goes askew is we’re going to feed them content that we know they’re going to be really excited about. This is troubling on many levels. I have soured on using the term content to describe online writing and other media because term itself lacks content – albeit that makes it oddly fitting for much of what is out there. But worse than content without content is the phrase feed them content. That is just awful. Long-time readers will know that I promote using feed readers as an alternative to algorithms precisely because it is an active way of reading and watching things on the internet – requiring the reader/viewer to intentionally choose his or her inputs and decide what is worth his or her time. That is no good for Ms. Kovacs – she wants users instead of viewers. To the extent she wants customers, she wants them to be almost comatose and attached to a content IV bag.

(Aside: I am also concerned about really excited about. That should be really. I do not care what usage guide X or Y says. Let us distinguish between really and very.)

In Ms. Kovacs’ excitement about introducing new ways to feed her users so that they are properly engaged, she inadvertently and flippantly evinces her company’s lack of respect for its customers. The moral here is not to not use Peacock or any other service. For example, if I still closely followed the NBA like I used to, perhaps I would want a Peacock solution to watch games next season (but not to be “fed content”). The lesson here in the context of streaming services is for people to be active customers and viewers (or players, apparently) instead of consumers and users. This principle applies in choosing which services, if any, to sign up for – wherein prospective customers/viewers can consider the ends (worthwhile media in the service’s library) and means (cost, annoyances, et cetera). After signing up, customer/viewers can opt to use the service how they want to use it instead of how the service wants them to use it. This may mean actively perusing the service’s catalog (while being wary of building a backlog through unproductive window shopping) instead of relying exclusively or primarily on its algorithmic recommendations, which may well be tailored to benefit the service before the interests of the active customer/viewer. In the context of new features or annoyances, the active customer/viewer may take a moment to ask him or herself why the service has introduced such a feature (never forget to evaluate purpose). Is the feature designed to provide genuine value to the active customer/viewer or is it intended to turn the customer/viewer into a more valuable consumer/user for the service? In this way, even streaming services can, (sometimes) contrary to their design, be used productively.