In early 2021, I published a series of articles covering the birds of the January 1897 issue of Birds: A Monthly Serial or Birds: Illustrated by Color Photography. The series remained dormant since I finished that inaugural issue, but today I return with a bird from the February 1898 issue of the same magazine – the saw-whet owl. This is the second time that the saw-whet owl has featured in The New Leaf Journal. Last year I covered the story of an unfortunate saw-whet owl that found itself in Rockefeller Center after it had stopped to take a rest in a large tree that was chopped down for the purpose of becoming the Rockefeller Center Christmas Tree. Today, we learn about the life and habits of the saw-whet owl generally, as described in Project Gutenberg sources and contemporary resources.

See my companion article for a brief poem on the saw-whet owl re-printed from Birds: Illustrated by Color Photography.

Sources

For this article, I will rely primarily on four Project Gutenberg resources to describe the saw-whet owl.

My main source will be the February 1898 issue of Birds: Illustrated by Color Photography, which includes the saw-whet owl among the birds of the issue. You will find the link to the magazine on Project Gutenberg here.

Our second source is Cavity-Nesting Birds of North American Forests, published by the Forest Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 1977. The full issue is available here.

I will supplement these two sources with a couple of passages from other books on Project Gutenberg and authoritative modern resources on birds. Chief among the modern resources are the Cornell Lab’s All About Birds site and the website of The Owl Research Institute.

About the Saw-Whet Owl

Let us learn about the saw-whet owl from our sources.

The Name and Cry of the Saw-Whet Owl

The 1898 magazine on birds began its saw-whet owl content by addressing the small owl’s “curious” name, opining that “when we hear its shrill, rasping call note, uttered perhaps at midnight, we admit the appropriateness of ‘saw-whet.’” What made the name appropriate? “It resembles the sound made when a large-toothed saw.”

Upon further research, it appears that the magazine’s attribution of the saw-whet owl’s name to its cry sounding like a saw was about right. A 2015 post at Mass Audubon stated that the name derived from the owl’s cry being compared to “the sound of a saw being sharpened on a whetstone…” On November 16, 2020, Ms. Vindi Sekhon of Wildlife Rescue noted that it is “widely speculated” that the saw-whet owl earned its name because its call sounds like a saw being sharpened against whetstone, but that “[t]he etymology of the name is uncertain.”

Cornell’s All About Birds agrees that the name of the saw-whet owl derives from its voice and that the most common explanation is the whetstone theory, but it notes that “there is no consensus as to which of [the saw-whet owl’s] several calls gave rise to the name.”

The scientific name for the saw-whet owl is Aegolius acadicus.

Accounts of the Sound of the Saw-Whet Owl

What does the saw-whet owl sound like? Cornell University has a selection of saw-whet owl recordings available for listening.

Ernest Thompson Seton (1860-1946) spelled the “water-dripping sound of the saw-whet owl” in Wild Animals I Have Known:

Tonk tank tenk tink Ta tink a tonk a tink a tink a Ta ta tink tank ta ta tonk tink Drink a tany a drink a drunk

The Owl Research Institute notes that there is a slight difference between the voice of male and female saw-whet owls. It describes the voice of the male saw-whet owl as follows:

[A] monotonous series of whistles, all on the same pitch; also a short series of ‘ksew-ksew-ksew’ notes, often compared to a back and forth sound when filing a saw.

Regarding the female saw-whet owls, the Owl Research Institute notes that their voice is “softer and less consistent than males.”

Where Does the Saw-whet Owl Live?

The 1898 Bird magazine stated that the saw-whet owl most commonly lives in the woodlands, but was sometimes found in farm houses and cities – most notably Chicago.

Our later sources described the habitat of the saw-whet owl in more detail. The 1977 report by the U.S. Forest Service described the saw-whet owl’s as living in “the deep north woods.”

It added that saw-whet owls “nest in the Rocky Mountains up to about 11,000 feet” and in most forest types in the northern half of the United States.

Cornell’s All About Birds explains that saw-whet owls breed in forests in southern Canada and the northern and western United States, all the way down through central Mexico. They “winter in dense forest” throughout their breeding range, but can be found in other parts of the United States in different times of the year. It is worth noting that Cornell’s Bird’s of North America map is a bit different than the 1977 map pictured above.

The 1898 article described saw-whet owls as not being migratory, but instead “irregular wanderer[s] in search of food during autumn and winter.” This view seems to be in accord with contemporary accounts of the owl’s life-style. However, Cornell’s All About Birds describes the saw-whet owl as being migratory but adds that its migratory patterns “are poorly understood.”

The Saw-whet Owl’s Appearance

The saw-whet owl that inadvertently took a trip to New York City by resting in the 2020 Rockefeller Center Christmas Tree garnered attention in part because of its small size. There were pictures of the tiny owl wrapped in a blanket and staring at a camera while in a cardboard box surrounded by pine tree branches.

The Size of the Saw-whet Owl

The 1898 Bird magazine noted its small size as one of its most recognizable features:

The small size of the Saw-whet and the absence of ears, at once distinguish this species from any Owl of eastern North America, except Richardson’s, which has the head and back spotted with white, and legs barred with grayish-brown.

(Richardson’s owl is commonly known today as the boreal owl. You can learn more about it on the Owl Research Institute website.)

The saw-whet owl received a single mention in an 1899 book titled The Children’s Book of Birds, which emphasized its stature by referring to it as “[t]he funny little saw-whet owl.”

The 1977 guide by the Forest Service listed the saw-whet owl as being approximately 7 inches in length and possessing a 17-inch wingspan. This is generally in accord with the current ranges provided by Cornell’s All About Birds, which list the owl as being between 7.1 and 8.3 inches long and having a wingspan of 16.5 to 18.9 inches. Cornell lists the tiny owl as weighing between 2.3 and 5.3 ounces. The Owl Research Institute provides slightly different size and weight ranges. It notes that females are usually larger than males, but both range from 6.7 to 8.3 inches in length and have wingspans from 18.1 to 22.0 inches.

The Color and Features of the Saw-whet Owl

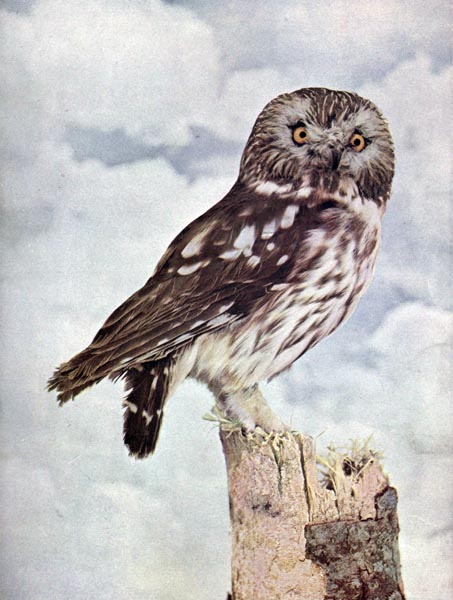

The Owl Research Institute explains that male and female saw-whet owls share the same appearance. The saw-whet is “[a] small reddish-brown owl with a large, round head, yellow eyes, black beak, and feathered feet.”

The 1898 Bird magazine featured a section written from the perspective of a child and his mother reading the magazine. Here, the child and his mother agreed that the saw-whet was less handsome than the snowy owl. But they did praise the saw-whet for some of the features described by the Owl Research Institute, noting that the “little fellow’s feet have on black shoes with yellow soles” and that “[h]is eyes glow like topaz…”

Cornell’s All About Birds described the saw-whet as:

A tiny owl with a catlike face, oversized head, and bright yellow eyes, the Northern Saw-whet Owl is practically bursting with attitude.

Perhaps it is bursting with attitude in its natural habitat. However, those of us who were introduced to the poor traumatized saw-whet wrapped in a blanket after being found in the Rockefeller Center Christmas Tree saw one thing in its “bright yellow eyes.”

Trauma. Those eyes had seen things.

Saw-whet Owl Courtship

Sadly, neither of my main Project Gutenberg resources on saw-whet owls described their courtship behavior. Cornell’s All About Birds explains that saw-whet owls are ordinarily monogamous, but males may occasionally have more than one mate “when prey is abundant.” Males court females beginning in late January and ending in May. When a female responds to the male’s mating call, “[t]he male circles her about 20 times in flight before landing beside her and presenting a prey item.” Saw-whet owls find new mates each mating season.

Saw-whet Owl Nesting

The saw-whet owl was the cover bird for the U.S. Forest Service’s 1977 guide Cavity-Nesting Birds of North American Forests for a good reason. The book explained:

These small owls prefer to nest in old flicker or other woodpecker holes. Nesting habitat may be improving in areas where Dutch Elm disease has infested many elms, and woodpeckers have drilled nest holes.

(Internal citations omitted.)

The 1898 magazine described saw-whet owl nesting similarly:

These birds nest in old deserted squirrel or Woodpecker holes and small hollows in trees. The eggs—usually four—are laid on the rotten wood or decayed material at the bottom. They are white and nearly round.

Cornell’s All About Birds provided more detail on saw-whet owl nesting, but the information is similar to the aforementioned resources. Cornell adds that “[f]emales probably choose the nest site, although males sometimes participate…” Saw-whet owls “lay their eggs on debris at the bottom of the cavity [in the nest]—such as woodchips, twigs, moss, grass, hair, small mammal bones, or old starling nests—without adding new material to the nest.” A female saw-whet owl lays four-to-seven eggs and the incubation period for the eggs is 26-29 days.

Building a Saw-Whet Owl Nesting Box

The 1977 U.S. Forest Service report on cavity-nesting birds noted that saw-whet owls will use man-made nesting boxes provided that the nesting boxes have the correct dimensions:

Saw-whets will use nesting boxes if sawdust or straw is provided. Nest boxes should be 6 x 6 x 9 inches with a 2.5-inch entrance hole.

The guidance on building nesting boxes for saw-whet owls changed a bit over the years. The U.S. Forest Service’s 1977 recommendation was for 6 x 6 x 9 inch nesting boxes with a 2.5 inch entrance hole. A 1916 book (1919 ed) called Bird Houses Boys Can Build included dimensions for saw-whet owl nesting boxes in its pages. Citing to guidance from issue 609 of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Farmer’s Bulletin, the book recommended that saw-whet owl nesting boxes be 6 x 6 x 10-12 inches instead of 6 x 6 x 9 inches. It was in accord with the 1977 guidance regarding a 2.5 inch entrance hole. The 1916 guidance recommended building the boxes 12-20 feet above ground.

I found modern saw-whet owl nest box guidance on the Cornell Lab’s NestWatch page for the diminutive owl. NestWatch recommends affixing the saw-whet owl nest box to a live tree 12 to 15 feet above the ground, and states that boxes should be at least 800 feet apart. Saw-whet owl nest boxes should face south. NestWatch provides slightly different recommendations for dimensions than the U.S. Government’s 1916 and 1977 guidance. It recommends dimensions of 10 x 11 3/4 x 14 inches and an entrance hole of 3 inches. For those of you who live in an area amenable to saw-whet owl nesting, the site has a free downloadable saw-whet owl nest box plan.

What Do Saw-Whet Owls Eat?

The 1898 Bird magazine included a brief interview with a saw-whet owl. Mr. Saw-whet described his diet:

You never see me out in the day time, no indeed! I know when the mice come out of their holes; I am very fond of mice, also insects. I like small birds, too—to eat—but I find them very hard to catch.

The 1977 U.S. Forest Service guide book includes similar information – albeit not from a first-owl perspective. It notes that the saw-whet owl is a “nocturnal hunter” and that its diet consists “mostly [of] small mammals and insects.”

Cornell’s All About Birds expands on this a bit. It adds that when female saw-whet owls are incubating and brooding young saw-whets, the males provide nearly all the food. In one note that highlights the broad range of the saw-whet owl, it explained that “saw-whets that live along the coasts may eat intertidal invertebrates such as amphipods and isopods.”

Saw-whets must be careful, however. Perhaps owed to their small size, All About Birds stated that they are sometimes preyed upon by larger birds of prey.

Conclusion

The saw-whet owl gained recognition in 2020 from the Rockefeller Center Tree incident. When I saw that the saw-whet had been covered by Birds: Illustrated By Color Photography, I knew that a New Leaf Journal follow-up was in order. I hope you enjoyed the saw-whet owl survey, and if you happen to live where the little owls nest, you may consider building a nesting box for a pair.