Today, we cover the penultimate bird in the January 1897 issue of Birds: A Monthly Serial, also known as Birds: Illustrated By Color Photography – the Red-Rumped Tanager. The bird’s name is a bit of a spoiler, but I think that you will find plenty of surprises and points of avian interest in the forthcoming content. For one, this is the first time that we will have to work to figure out exactly what bird we are talking about in modern terms. But before we get into whether this is a Scarlet Tanager or a Scarlet-Rumped Tanager, or whether it’s Cherrie’s Tanager or Passerini’s Tanager, we will start with a classic photo of the bird and its own self-introduction. The original article contains a poem, but I will reserve that for a future article.

You can follow see the original Red-Rumped Tanager content at Project Gutenberg and The Internet Archive.

The Red-Rumped Tanager, Illustrated

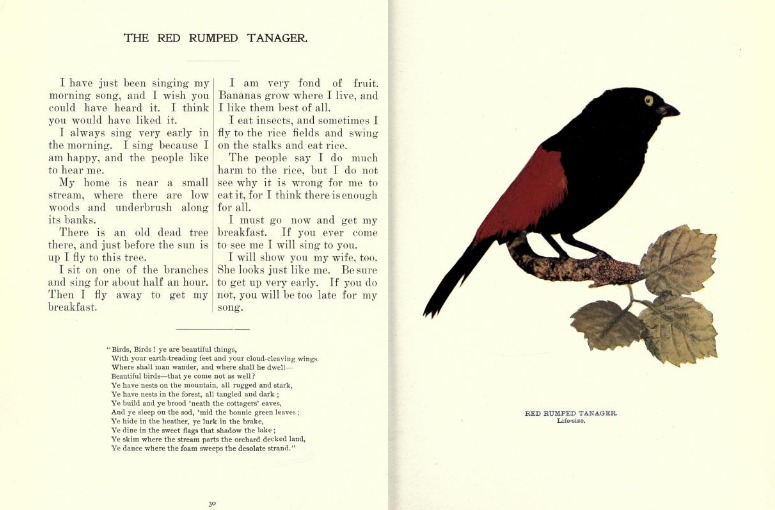

This Red-Rumped Tanager content begins with a beautiful picture of the titular bird.

The Red-Rumped Tanager is the third bird that we have covered with a color in its name – following the Golden Pheasant, Red Bird of Paradise, and Yellow Throated Toucan. Similarly to its predecessors in the issue, the name is no misnomer. The Red-Rumped Tanager indeed has a red rump. It may be the least colorful bird that we have covered, but a few colors are needed when you are clad in such a bold red and black.

Mr. Red-Rumped Tanager’s Self-Introduction

The editors of Birds yielded the floor to the Red-Rumped Tanager for his self-introduction to young readers. The Red-Rumped Tanager joins every bird in the issue thus far except for the Golden Pheasant and the Cock-of-the-Rock in introducing himself to readers.

How do I know that it is Mister Red-Rumped Tanager? He tells us about his wife. That is probably decisive.

Below, I recount Mr. Red-Rumped Tanager’s letter in stages.

The Sound of Mr. Red-Rumped Tanager’s Music

Mr. Red-Rumped Tanager ceases singing a song before offering some comments about himself to the readers of Birds:

I have just been singing my morning song, and I wish you could have heard it. I think you would have liked it.

Mr. Red-Rumped Tanager

I wish that we could have heard it too. However, thanks to the wonders of technology, you can listen to him sing here.

When does the Red-Rumped Tanager like to sing? “Very early in the morning,” he says. While the Red-Rumped Tanager does not necessarily sing for people, he noted that “the people like to hear me.” Count me among the people. And you?

Mr. Red-Rumped Tanager tells us that every morning, he flies from his home near a small stream “where there are low woods and underbrush along its banks,” to an old dead tree just before the sun rises. On that tree, he sings for about half an hour. After he completes his song, he flies off for breakfast.

Breakfast?

Mr. Red-Rumped Tanager fancies fruit. His favorite fruit, he reports, is the banana. Fortunately, wherever he lives, bananas are plentiful.

Mr. Red-Rumped Tanager taught young readers a good lesson about not being a picky eater. Although his favorite food is banana, he also enjoys insects and rice. He not only enjoys eating rice, but also swinging on the stalks.

Apparently, Mr. Red-Rumped Tanager’s rice-consumption was not as popular with the locals as was his singing. He did not understand the problem. “The people say I do much harm to the rice, but I do not see why it is wrong for me to eat it, for I think there is enough for all.”

Speaking of Breakfast

The Red-Rumped Tanager reported at the start of his letter that he had just finished singing. Studious readers will recall that after he is done with his song, he always sets out for breakfast. And so, “I must now go and get my breakfast.” However, Mr. Red-Rumped Tanager invited young readers to visit again, and he promised that he would sing them a song if they did. Furthermore, he promised that he would show readers his wife, who looks “just like” him. However, he warned the kids that they would have to “get up very early,” lest they miss his song.

Red-Rumped Tanager Facts

After Mr. Red-Rumped Tanager left for breakfast, the editors of Birds took over to regale young readers with facts about our scarlet friend. Here is a fact – he is known today as the Scarlet-Rumped Tanager.

As you will see, most of the article on the Red-Rumped Tanager consists of accounts by a nineteenth century naturalist – George K. Cherrie.

The Happy Tanager Family Is Smaller Than Expected

Rather than focusing on the Red-Rumped Tanager alone, the editors began with a broader look at the Tanagers.

“An American family, the Tanagers are mostly birds of a very brilliant plumage. There are 300 species, a few being tropical birds. They are found in British and French Guiana, living in the latter country in open spots of dwellings and feeding on bananas and other fruits. They are also said to do much harm to rice fields.” A fact disputed by Mr. Red-Rumped Tanager.

I discovered from a quick look at Wikipedia that the Birds editors may have overestimated the number of Tanagers. According to sources cited to by Wikipedia, there were traditionally thought to be 240 birds in the Tanager family – Thraupidae. That is, some birds that were thought to be members of the Thraupidae family were actually members of other avian families, including the cardinal family. Among these, is the Scarlet Tanager – which is apparently in the cardinal family. That bird would feel at home here in The New Leaf Journal – for I wrote about its brethren (or feathren?) in these pages last spring. But what if I told you that our Red-Rumped Tanager, despite looking almost exactly like the Scarlet Tanager (which is a cardinal), is, in fact, a Tanager?

Our Red-Rumped Tanager is a Tanager, However

When I first tried to identify the “Red-Rumped Tanager” in modern terms, I thought I found it when I came across the Scarlet Tanager. Not so, I discovered. I was looking for the “Scarlet-Rumped Tanager,” also known as Cherrie’s Tanager. This bird, unlike the Scarlet Tanager, is, in fact, a member of the Tanager (Thraupidae) family. Thus, while Birds overestimated the number of Tanagers, it did not wrongly classify Mr. Red-Rumped Tanager. The Scarlet Tanager spends its breeding season in the United States and Canada – but the Scarlet-Rumped Tanager restricts itself to Southern Mexico and Central America all year around.

The mystery did not end there – however. The Scarlet-Rumped Tanager itself has been split into two kinds of Tanagers – Cherrie’s Tanager and Passerini’s Tanager. See Lee’s Birdwatching Adventures 2012 exploration of the issue regarding the same article.

Because Birds cites to a long passage from George K. Cherrie himself about the Red-Rumped Tanager, it seems obvious that Birds was thinking of Cherrie’s Tanager. However, given that the distinction between Cherrie’s Tanager and Passerini’s Tanager was made well after, it is not entirely clear that the Red-Rumped Tanager content is exclusively about what is now classified as Cherrie’s Tanager. However, for the purpose of the following discussion, I will assume for the most part that we are talking about Cherrie’s Tanager. Cornell’s eBird website, for example, still groups both varieties of Scarlet-Rumped Tanagers together, while distinguishing between them in multimedia content.

Some Additional Red-Rumped Tanager Facts

Before we proceed to the classic naturalist accounts of the Red-Rumped Tanager, I decided to discuss some modern sources on the bird.

Despite what Mr. Red-Rumped Tanager suggested, female Red-Rumped Tanagers are typically yellow with olive accents. You can see a comparison of the typical male and female at The Firefly Forest. Females of the Passerini’s variety have “a grey head, olive upperparts … brownish wings and tail and ochre underparts.”

Wikipedia notes, as did Mr. Red-Rumped Tanager, that the birds eat fruit and insects.

Fortunately the Red-Rumped Tanager is doing well – its conservation status is “Least Concern.”

Audubon explains that female Scarlet Tanagers (the North American-variety) typically lay 2-5 eggs, which are “pale blue-green, with spots of brown or reddish brown often concentrated at larger end.”

Cornell’s ebird site has many photos, videos, and audio recordings of the bird of the day (these include “Cherrie’s” and “Passerini’s” varieties). Drexel University has a smaller collection of photos of Cherrie’s Tanager specifically. While I agreed with Mr. Red-Rumped Tanager that he is a wonderful singer, I must note that some have apparently compared his singing of his distant cardinal relative, the Scarlet Tanager, to “a robin with a bad cold.”

Accounts From George K. Cherrie

After their brief introduction, the Birds editors reprinted a long account of the Red-Rumped Tanager from George K. Cherrie, a prominent naturalist of his day. Cherrie wrote his observations and thoughts about the bird in the July 1893 issue of “The Auk.” I will break the account into smaller sections for easy reading.

Cherrie’s Observations of the Red-Rumped Tanager

Cherrie wrote that he collected many Red-Rumped Tanagers in Costa Rica. Therein, he found “males wearing the same dress as females.” This is likely why Mr. Red-Rumped Tanager reported that his wife looked the same as him. According to Cherrie’s observations, “it is clear that the males begin to breed before they attain fully adult plumage, and that they retain the dress of the female until, at least, the beginning of the second year.”

Cherrie on the Red-Rumped Tanager’s Place of Honor Among Song Birds

Cherrie wrote that “in spite of [the Red-Rumped Tanager’s] rich plumage, and being a bird of the tropics, it is well worthy to hold a place of honor among the song birds.” Some of our past tropical birds may resent the implication there. But I digress. Below, I reprint the rest of Cherrie’s account of the Red-Rumped Tanager’s song in its entirety.

A Song Worth Listening to Again

And if the bird chooses an early hour and a secluded spot for expressing its happiness, the melody is none the less delightful. At the little village of Buenos Aires, on the Rio Grande of Terraba, I heard the song more frequently than at any other point. Close by the ranch house at which we were staying, there is a small stream bordered by low woods and underbrush, that formed a favorite resort for the birds. Just below the ranch is a convenient spot where we took our morning bath. I was always there just as the day was breaking. On the opposite bank was a small open space in the brush occupied by the limbs of a dead tree. On one of these branches, and always the same one, was the spot chosen by a Red-rump to pour forth his morning song.

Some mornings I found him busy with his music when I arrived, and again he would be a few minutes behind me. Sometimes he would come from one direction, sometimes from another, but he always alighted at the same spot and then lost no time in commencing his song. While singing, the body was swayed to and fro, much after the manner of a canary while singing. The song would last for perhaps half an hour, and then away the singer would go. I have not enough musical ability to describe the song, but will say that often I remained standing quietly for a long time, only that I might listen to the music.

George K. Cherrie

My Thoughts on Cherrie’s Account

“I have not enough musical ability to describe the song, but will say that often I remained standing quietly for a long time, only that I might listen to the music.”

That is a lovely phrase by Cherrie, and it is no surprise that Mr. Red-Rumped Tanager was confident that young readers of Birds would enjoy his song just as Cherrie did.

Exiting With a Final Song

This was, without question, the most difficult of the bird articles to write. I found myself a bit confused as to which bird we were talking about, and I may have had to re-write some portions about the “Scarlet Tanager” at some point. Maybe. Ideas for a future article?

The Red-Rumped Tanager article was one of the more clever pieces in the January 1897 issue of Birds. The editors used the Red-Rumped Tanager’s self-introduction to make digestible the facts reported by Cherrie for younger readers. Older readers and those with higher reading comprehension could find joy in seeing the details from Mr. Red-Rumped Tanager’s account in Cherrie’s descriptions.

While the article is not entirely timely, it makes for good reading for young and old alike today. The subsequent history in classifying the Red-Rumped Tanager add some interest to the classic bird content.

My next article will cover the final bird of the issue and one that should be familiar to most readers – The Golden Oriole.