We begin the second half of the birds covered in the June 1897 edition of Birds, A Monthly Serial, or Birds: Illustrated by Color Photography with the sixth bird in the issue – the Cock-of-the-Rock. The first five birds each told their own side of the story before the editors of the magazine weighed in with further facts about the bird. Sadly, the editors did not reach the Cock-of-the-Rock for comment. Instead, we have a long piece full of facts and stories about the bird with a truly striking hairdo (or feather-do?). I dare say this bird has the most striking profile since the second bird we covered, the Resplendent Trogon.

You can follow along with the original Cock-of-the-Rock content at Project Gutenberg or The Internet Archive.

The Cock-of-the-Rock, Illustrated

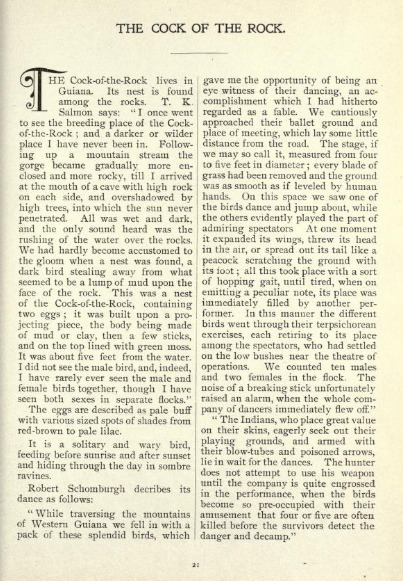

Below, you will find the Cock-of-the-Rock in full color. He certainly cuts a profile.

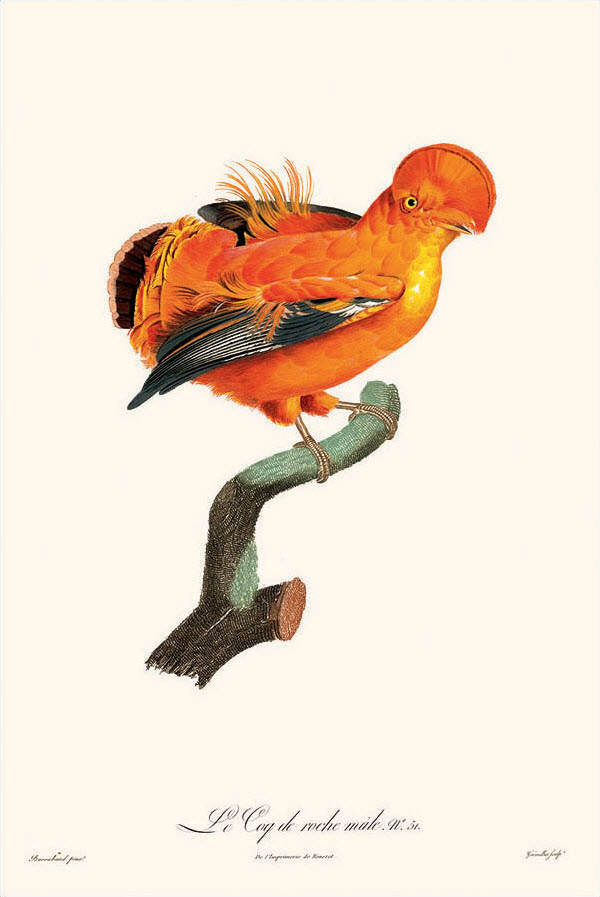

The attention-grabbing aspect of the Cock-of-the-Rock’s appearance is his head. A dramatic poof of feathers covers the front of his face, almost entirely concealing his small beak. His eye, positioned at the side of his head, is entirely uncovered. What an interesting looking bird. I look forward to learning more as we work through the article. His main color is somewhere in the burnt orange to red range, with black and gray on his wings and tail.

A renowned nineteenth century English explorer by the name of Charles Waterton described the appearance of the Cock-of-the-Rock in his book titled “Wanderings in South America”:

He is about the size of a fantail-pigeon, his colour a bright orange, and his wings and tail appear as though fringed; his head is ornamented with a super double-feathery crest, edged with purple.

Charles Waterton

Facts About the Cock-of-the-Rock

Unlike the earlier birds, the Cock-of-the-Rock does not speak directly to the audience. Perhaps it is because the magazine describes him as “a solitary and wary bird” in the forthcoming section. The editors gave the Cock-of-the-Rock a full-page description, which is more than the Golden Pheasant and the Australian Grass Parrakeet received in the last two articles. We will examine the Cock-of-the-Rock content in the magazine and supplement it with additional information.

Where Does the Cock-of-the-Rock Live?

The editors tell us that the Cock-of-the-Rock lives in Guiana. There, “[i]ts nest is found among the rocks.”

A gentleman by the name of T.K. Salmon described the habitat of the Cock-of-the-Rock:

I once went to see the breeding place of the Cock-of-the-Rock; and a darker or wilder place I have never been in. Following up a mountain stream the gorge became gradually more enclosed and more rocky, till I arrived at the mouth of a cave with high rock on each side, and overshadowed by high trees, into which the sun never penetrated. All was wet and dark, and the only sound heard was the rushing of the water over the rocks. We had hardly become accustomed to the gloom when a nest was found, a dark bird stealing away from what seemed to be a lump of mud upon the face of the rock. This was a nest of the Cock-of-the-Rock, containing two eggs; it was built upon a projecting piece, the body being made of mud or clay, then a few sticks, and on the top lined with green moss. It was about five feet from the water. I did not see the male bird, and, indeed, I have rarely ever seen the male and female birds together, though I have seen both sexes in separate flocks.

T.K. Salmon

He had never been in “a darker or wilder place” than where he found the Cock-of-the-Rock. One gets the impression from reading that Mr. Salmon visited many interesting places.

Up-to-Date Information on Where the Cock-of-the-Rock Lives

To start, we should note that there are two species of Cock-of-the-Rock. The Andean Cock-of-the-Rock and the Guianan Cock-of-the-Rock. Unsurprisingly from the text of the article, we are dealing with the Guianan variety.

According to Cornell University’s eBird site, the Cock-of-the-Rock lives in “lowland rainforest near rock formations that provide nest sites.” Its range covers parts of Colombia, Brazil, Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname, and French Guiana. Thus, the bird’s range is a bit wider than the magazine suggested.

The Cock-of-the-Rock is Solitary

The editors describe the Cock-of-the-Rockas “a solitary and wary bird, feeding before sunrise and after sunset and hiding through the day in sombre ravines.” Perhaps that is why the editors did not reach a Cock-of-the-Rock for comment. Waterton provided a similar account: “He passes the day amid gloomy damps and silence, and only issues out for food a short time at sunrise and sunset.”

Cock-of-the-Rock Eggs

The editors describe Cock-of-the-Rock eggs “as pale buff with various sized spots of shades from red-brown to pale lilac.”

I found an interesting contemporary note while researching the Cock-of-the-Rock. The Guianan Cock-of-the-Rock was bred in captivity for the first time in 2008 at the Dallas World Aquarium. It appears that the Dallas World Aquarium still has the Cock-of-the-Rock as part of its collection.

The Dallas site includes another interesting note that explains why Mr. Salmon did not see a male Cock-of-the-Rock tending to the nest he found. According to the Dallas World Aquarium, male Cock-of-the-Rocks are polygamous and females raise chicks without any help from males. This is a bit less romantic than many of the previous birds we have covered. But we have more to cover on the subject of Cock-of-the-Rock mating.

Cock-of-the-Rock Mating Dances

The Cock-of-the-Rock is known for its mating dance as well as its striking appearance. Rather than describe the mating dance myself, I will reprint the editors’ reprinting of an account by the nineteenth century German explorer, Robert Schomburgk:

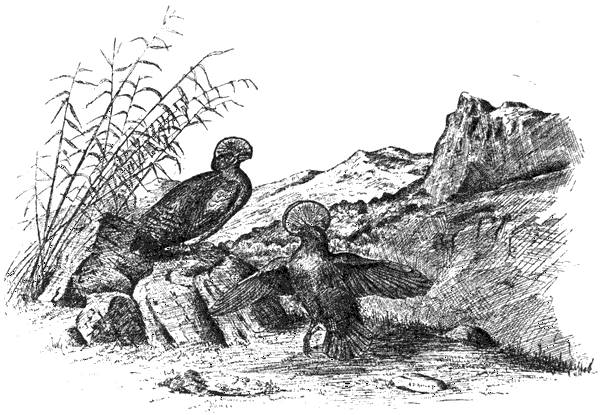

While traversing the mountains of Western Guiana we fell in with a pack of these splendid birds, which gave me the opportunity of being an eye witness of their dancing, an accomplishment which I had hitherto regarded as a fable. We cautiously approached their ballet ground and place of meeting, which lay some little distance from the road. The stage, if we may so call it, measured from four to five feet in diameter; every blade of grass had been removed and the ground was as smooth as if leveled by human hands. On this space we saw one of the birds dance and jump about, while the others evidently played the part of admiring spectators. At one moment it expanded its wings, threw its head in the air, or spread out its tail like a peacock scratching the ground with its foot; all this took place with a sort of hopping gait, until tired, when on emitting a peculiar note, its place was immediately filled by another performer. In this manner the different birds went through their terpsichorean exercises, each retiring to its place among the spectators, who had settled on the low bushes near the theatre of operations. We counted ten males and two females in the flock. The noise of a breaking stick unfortunately raised an alarm, when the whole company of dancers immediately flew off.

Robert Schomburgk

Below is an illustration of the Cock-of-the-Rock dance by Hubert D. Astley for Edmund Selous’s 1901 book, “Beautiful Birds”:

More Bird-Harm, But Good News Too

We managed to go a couple of bird essays without too much avian violence, but the trend ends here. The editors continued with Schomburgk’s account. Therein, he wrote that Indians valued the Cock-of-the-Rock for their skins, and they took advantage of Cock-of-the-Rock mating dances to fall a number of the performers with “blow-tubes and poisoned arrows.”

Despite this unfortunate Cock-of-the-Rock hunting, I am happy to report that the Guianan Cock-of-the-Rock’s conservation status is classified as “Least Concern.” Despite the previous emphasis on the solitary nature, groups of Cock-of-the-Rocks during mating season sound the alarm when a predator is near to the benefit of the entire group.

Extra Guianan Cock-of-the-Rock Content

While looking for information about the Guianan Cock-of-the-Rock, I found several additional things of interest in include outside of the magazine article. Because the bird did not get to speak for himself, it is only fair that we add some additional information and pictures to his article here.

What About the Female Cock-of-the-Rock?

The editors neglected to tell us what the female Cock-of-the-Rock looks like. According to The Dallas World Aquarium: “Females are a drab brown color. Their bill is black with a yellow tip and they have a smaller crest than the males.” They do not seem to dance like the males, but perhaps they are tired from the trials of single parenthood.

Extra Content – Comparing the Cock-of-the-Rock to the Resplendent Trogon

Our Bird magazine does not tend to connect the birds that it discusses within an issue. Beautiful Birds, which I referenced supra, happened to discuss the Resplendent Trogon, which we covered second in the series, immediately after the Cock-of-the-Rock. The author, Edmund Selous, wrote a brief comparison of the two colorful South American birds:

[B]esides [the Resplendent Trogon’s] splendid tail-feathers, this beautiful bird has a crest on his head, which is something like the one the Cock-of-the-Rock has on his, for it is of the same tea-cosy shape, only it is green instead of crimson, and it does not quite cover up the beak. So perhaps you will think that, as the Cock-of-the-Rock is all blood-red, with a tea-cosy crest on his head, this beautiful golden-green Trogon, with the tea-cosy crest on his head, is all golden-green. But no, all the lower part of him—that part which is hidden when he sits down—instead of being golden-green, is the most splendid vermilion, as bright a colour—although it is not quite the same—as the Cock-of-the-Rock’s himself. Just think, golden-green and splendidly bright vermilion! and you cannot think how beautiful the one looks against the other. Whether they would look quite so well together in a dress I am not quite sure, but your mother would know all about that.

Edmumd Selous from “Beautiful Birds” (1901)

Extra Illustration of the Cock-of-the-Rock

I saw a beautiful 1801-1805 illustration of the Cock-of-the-Rock on Wikipedia by Jacques Barraband, and decided to include it in the post:

Dancing into the Sunset with the Cock-of-the-Rock

Despite the lack of comment from the Cock-of-the-Rock himself, the bird proved to be an interesting one to read and write about. It appears that the Cock-of-the-Rock captured the imagination of many nineteenth century explorers, both for his appearance and elaborate courtship rituals. The article should be of interest to children today just as it surely was in 1897. The anecdotes from explorers are timeless. I would suggest including additional information about the Cock-of-the-Rock to complement the 1897 content.

For those who are interested in learning about more, I recommend visiting the ebird.org page for the Guianan Cock-of-the-Rock. The page includes a large library of pictures, videos, and audio recordings of the striking bird.

In our next article in the series, we will travel to New Guinea to visit the Red Bird of Paradise.