Today we will cover the first bird featured in the January 1897 edition of Birds: A Monthly Serial – the nonpareil. The Nonpareil is also known as the “painted bunting.” While I was tempted to move it down in the series order because you really cannot top a bird whose name suggests no other feathered friend is its equal, I decided to stick with the magazine’s order. Below, you will find pictures and content from the 1897 Birds magazine along with my thoughts and additional resources. I covered the magazine more generally in my introduction to this series.

You can see the original Nonpariel content on Project Gutenberg and The Internet Archive.

The Nonpareil, Illustrated

I decided to undertake the instant series after seeing the beautiful illustrations in Birds: A Monthly Serial. Below, you will find the illustration of the Nonpareil.

Mr. Nonpareil’s Self-Introduction

The Nonpareil section of the magazine begins with a self-introduction from the colorful bird himself (we know that the nonpareil is male because of his color, as we will explain in the article – we have previously covered other birds that have similar sex-based color distinctions). Let us turn things over to Mr. Nonpareil, with my commentary.

The Nonpareil of Many Names

Mr. Nonpareil begins by telling us that he earned his name “because there is no other bird equal to me.” While this may sound cocky, it is the truth behind the name “Nonpareil.” He adds that he goes by other names, including the “Painted Finch,” “Painted Bunting,” and “The Pope,” the latter because he “wear[s] a purple hood.” I did not think that he could top the name “Nonpareil” until I reached “The Pope.” Mr. Nonpareil is setting the bar very high. But I digress.

The most common English name for Mr. Nonpareil today appears to be the “Painted Bunting,” at least according to the National Audubon Society. Their website explains, however, that the Painted Bunting is still “[s]ometimes called the ‘Nonpareil,’ meaning ‘unrivaled,’ a fair way to describe the unbelievable colors of the male Painted Bunting.”

Century Dictionary Definitions of “Nonpareil”

As I suggested above, “nonpareil” is a word in its own right, separate from Mr. Nonpareil. Let us turn to The Century Dictionary, which was published from 1889-91, just a few years before Mr. Nonpareil’s interview.

“Nonpareil” the Word

The first definition offered by the dictionary is “[h]aving no equal; peerless.” Both Mr. Nonpareil and the National Audubon Society refer to this definition, so it is most on point. The second definition is also pertinent: “A … thing of peerless excellence; nonesuch; something regarded as unique in its kind.”

I should digress to note that “nonesuch” is a fine synonym. Century offers the following definition of “nonesuch”: “Formerly, a person or thing such as to have no parallel; an extraordinary thing; a thing that has not its equal.” While “nonesuch” is a fine word, “nonpareil” is better for a bird.

Century provides an elegant usage example for its first definition for “nonpareil,” from Whitlock’s Manners of English People:

The most nonpareil beauty of the world, beauteous knowledge, standeth unguarded, or cloistered up in mere speculation.

Usage example of “nonpareil” from The Century Dictionary – quoted from Whitlock, Manners of Eng. People

“Nonpareil” the Bird

The third definition covers Mr. Nonpareil himself:

The painted finch or painted bunting, Passerina or Cyanospiza cris, so called from its beauty.

Century Dictionary definition of “nonpareil” in its ornithological meaning.

Mr. Nonpareil is Passerina cris. The cyanospiza cris refers to the closely related indigo bunting, although its binomal name is now passerina cyaena. Can two buntings be nonpareil? In the interest of simplicity, let us set that concern aside.

Century offers a pretty usage example for Mr. Nonpareil, courtesy of F.R. Goulding’s “The Young Marooners”:

The nonpareil hidden in the branches sat whistling plaintively to its mate.

Usage example of “nonpareil” from The Century Dictionary – quoted from F.R. Goulding, Young Marooners, xxxvi

With our definitions done, let us return to Mr. Nonpareil.

Mr. Nonpareil’s Pet Bird Life

Mr. Nonpareil is a pet, although most nonpareils live in the wild. The domesticated Mr. Nonpareil informs us that he lives in a cage, eats seeds, and is “very fond of flies and spiders.” Did he say “spiders”? We have spiders.

Mr. Nonpareil says that sometimes “they” allow him out of the cage to catch flies. “I like to catch them while they are flying.” To be expected of the nonpareil Mr. Nonpareil, always looking for a challenge. Furthermore, if the flies landed, something else might eat them, perhaps a spider or a centipede.

Having bragged about his diet, Mr. Nonpareil moves on to singing. “When I am tired I stop and sing. There is a vase of flowers in front of the mirror.” The vase is significant because Mr. Nonpareil can see himself in the glass. He sings as loud as he can because “they” like to hear him sing. I am sure that he has a lovely voice.

Mr. Nonpareil says that he takes a bath every day, wherein he “make[s] the water fly.” Am I wrong to sense in here a lesson for the children?

Mr. Nonpareil Yearns for the Wild

Lest one think that the comfortable pet Mr. Nonpareil knows nothing of nature, he disabuses them of that notion. “I used to live in the woods where there were many birds like me.” I am confused. How could there be many birds like the nonpareil Mr. Nonpareil? Well, let us let it slide and continue. “We built our nests in bushes, hedges, and low trees.” Mr. Nonpareil then says, with a hint of melancholy, “How happy we were.”

“My cage is pretty,” Mr. Nonpareil said, I imagine with a sigh,” “but I wish I could go back to my home in the woods.”

Well, that took a sad turn. You can imagine a child reading this and imagining having his or her own Mr. Nonpareil. The child is just about to run to the parents to ask for a nonpareil when he or she reaches the end of Mr. Nonpareil’s wistful reflections. Now, not only will the child not want a pet nonpareil, he or she will wonder if Fido the puppy or Mimi the kitten misses the woods too. This could end poorly. Adult supervision is most definitely recommended.

Was that the correct moral of the nonpareil story? The magazine tells us to turn to page 15 for more nonpareil content. Who am I to disobey? We have not only come this far, but we also pulled out the nineteenth century dictionary. Onward to page 15.

Nonpareil Facts

Page 15 offers facts about the nonpareil, written from a third-party perspective. I will work through these facts in the following subsections.

Where are Nonpareils Found in the Wild?

We learn that Nonpareils “are found in our Southern States and Mexico.” They are particularly “very numerous in the State of Louisiana and especially about the City of New Orleans.” Nonpareils “make [their] appearance in the Southern States the last of April,” just in time for their breeding season.

This information is consistent with the up-to-date information on the National Audubon Society website. Today, Painted Buntings are common in Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, and Louisiana during breeding season, as well as along the coast in the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida. The Audubon Society’s Field Guide states that “[t]hose nesting on [the] southern Atlantic Coast probably winter in Florida and [the] northwestern Caribbean; those nesting farther west probably winter in Mexico and Central America.” Regarding the winter, “[s]ome lucky Floridians have Painted Buntings coming to their bird feeders in winter.”

Nonpareil Habitats

The Birds magazine states that “[t]heir favorite resorts are small thickets of low trees and bushes, and when singing they select the highest branches of the bush.” This is in line with the contemporary information from the National Audubon Society: “This species is locally common in the Southeast, around bushy areas and woodland areas. It is often secretive, staying low in dense cover.”

What do Nonpareils Eat?

The magazine states that Nonpareils “are passionately fond of flies and insects and also eat seeds and rice.” Other than rice, this sounds similar both to what Mr. Nonpareil said and contemporary resources.

I will note one interesting fact from the National Audubon Society page. If you recall from earlier in the article, I noted the Indigo Bunting, another beautiful bird that is closely related to the Painted Bunting. According to the Audubon: “During migration, [the Painted Bunting] may forage in mixed flocks with Indigo Buntings. It is good to know that the Nonpareils are not too elitist to enjoy bugs with their bluer friends.

Nonpareil Breeding and Growth

The Nonpareil arrives in the southern United States for breeding season in April. The Birds magazine states that breeding season typically lasts until July. During the season, “two broods are raised.” “Their nests are made of fine grass and rest in the crotches of twigs of the low bushes and hedges.”

What do Nonpareil eggs look like? The Birds magazine tells us that “they have a dull or pearly-white ground and are marked with blotches and dots of purplish and reddish brown.”

Birds: A Monthly Serial, provides an eloquent description of how the Nonpareils grow up. Below, you will find the description quoted verbatim:

It is very pleasing to watch the numerous changes which the feathers undergo before the male bird attains his full beauty of color. The young birds of both sexes during the first season are of a fine olive green color on the upper parts and a pale yellow below. The female undergoes no material change in color except becoming darker as she grows older. The male, on the contrary, is three seasons in obtaining his full variety of colors. In the second season the blue begins to show on his head and the red also makes its appearance in spots on the breast. The third year he attains his full beauty.

From Birds: A Monthly Serial (Jan. 1897)

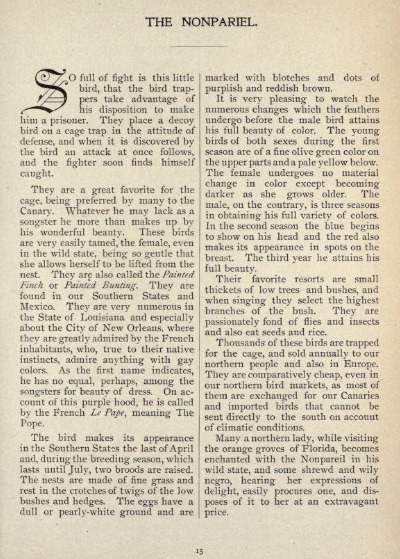

Catching Nonpareils

Mr. Nonpareil taught us that nonpareils were kept as pets. The magazine now teaches us how trappers catch nonpareils.

“So full of fight is this little bird, that the bird trappers take advantage of his disposition to make him a prisoner.” The magazine states that trappers would “place a decoy bird on a cate trap in the attitude of defense…” Once a nonpareil spots the decoy bird, “an attack at once follows, and the fighter soon finds himself caught.”

I see why Mr. Nonpareil left this part of his life story out. This sounds like an embarrassing way to be captured, especially if you walk around calling yourself nonpareil.

Why Were Nonpareils Valued as Pets?

The Birds magazine informs us that many pet owners prefer Nonpareils to Canaries. Despite Mr. Nonpareil bragging about his singing voice, the magazine suggests that they may be lacking in the singing department: “Whatever he may lack as a songster he more than makes up by his wonderful beauty.

Although trappers apparently take advantage of the fight of male Nonpareils to capture them, we are told that they “are very easily tamed.” This is especially the case for female Nonpareils: “[T]he female, even in the wild state, being so gentle that she allows herself to be lifted from the nest.”

The magazine states that the French inhabitants of New Orleans are especially fond of the Nonpareils: “[T]he French inhabitants, who, true to their native instincts, admire anything with gay colors.” Generalizations about French bird aesthetic preferences aside, Mr. Nonpareil’s “Pope” name apparently comes from French. “On account of [his] purple hood, he is called by the French Le Pape, meaning The Pope.”

The magazine reports that at the time of publication, at least, “[t]housands of these birds are trapped for the cage, and sold annually to our northern people and also in Europe.” They were all the more popular for the fact that they were cheaper than many other birds, and, unlike Canaries, could be sent directly to northern markets.

Nineteenth Century Racial Stereotyping in Children’s Magazines

Having benignly stereotyped the French to some extent, the magazine concluded with some lessn benign nineteenth century racial stereotyping, explaining that “shrewd and wily negro[es]” would catch Nonpareils for northern ladies struck by their beauty, “and dispose[] of it to her at an extravagant price.” Consider that our reminder that this magazine was published in 1897, not 2020. Children’s literature was different back in the day.

I included a full discussion of the article to offer a complete picture of the magazine, but those seeking to use the content as a friendly nature education tool for young children may consider some minor omissions from the end of the article.

Nonpareils are No Longer Pets

Much has changed since 1897. According to Wikipedia: “The male Painted Bunting was once a very popular caged bird, but its capture and holding is currently illegal.” Populations have declined, and the Painted Bunting is protected by the U.S. Migratory Bird Act.

While you cannot have a Mr. Nonpareil of your own as a pet, you can imagine what he would be like from the account in the January Birds: A Monthly Serial.

Review and Final Feathered Thoughts

I came into this article knowing very little about Nonpareils. After studying the magazine and conducting some maxillary research, I leave as something of a proverbial expert. To be sure, there is a risk to starting any series with something “nonpareil,” but having seen some of the forthcoming birds, I think they will hold their own.

How does the article itself hold up today? For the most part, I think the article fares well. The art is beautiful and the passage from the Nonpareil’s perspective was entertaining, albeit the information about pet Nonpareils was outdated. Were one to modify it to fix the outdated information and remove the one instance of racial stereotyping, I think that it would make fine content for children today. Subsequent birds will lack the two issues contained in this article. It should not be difficult to create a revised version of the article for young readers; indeed, one site already transcribed a modified version of the original article.

On the whole, I enjoyed putting together this first article in the series, and I hope you enjoyed reading about it and learning about the Nonpareil. The glowing reviews that the magazine printed in its first issue seem well-founded.