John Calvin Coolidge served as the 30th President of the United States from August 2, 1923, after assuming the presidency upon the death of then-President Warren Harding, to March 4, 1929. Shortly after leaving office, still in 1929, Coolidge published his autobiography. Coolidge’s autobiography was relatively short – numbering 266 pages. In it, the former President worked through his life, from childhood through his years in the White House, in a characteristically elegant way, wasting no words. At points, however, Coolidge wrote beautifully. His most eloquent sequence comes very early in the book, wherein he describes his mother, Victoria, who died on March 14, 1885, when young Calvin was only 13 years old.

Below, I will offer some brief background before reprinting Coolidge’s passage about his mother in its entirety.

Coolidge Family Background

John Calvin Coolidge was born on July 4, 1872, in Plymouth, Vermont. He remains the only president to have been born on Independence Day.

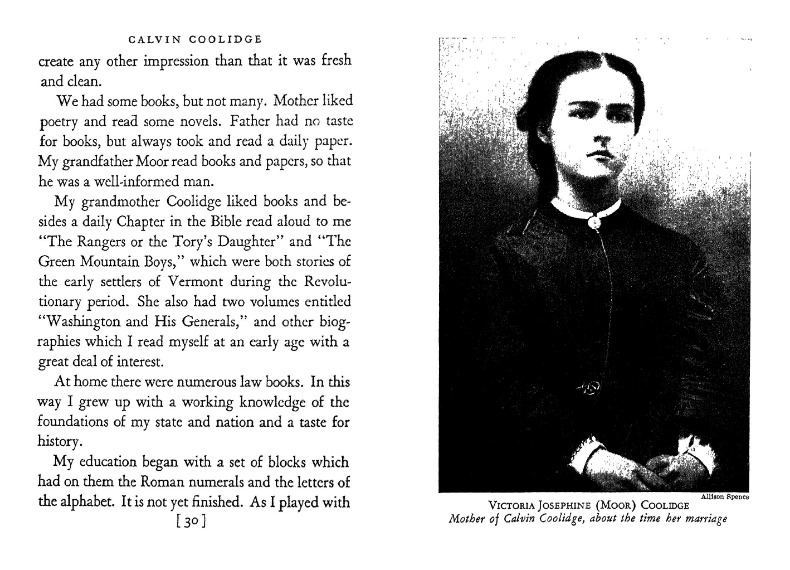

Coolidge was the son of John Calvin Coolidge Sr (1845-1926) and Victoria Josephine (Moor) Coolidge (1846-1885). Coolidge Sr. was a farmer and public servant, and would, in 1923, in his capacity as a notary public, administer the Presidential oath of office to his son in the family parlor.

Calvin Coolidge Describes His Mother

Coolidge prefaced his description of his mother by stating: “It seems impossible that any man could adequately describe his mother. I cannot describe mine.” Nevertheless, he proceeded to describe her.

Victoria Coolidge’s Background and Family

Coolidge wrote that his mother was the daughter of Hiram Dunlap Moor and Abigail (Franklin) Moor. He noted that “[s]he bore the name of two Empresses, Victoria Josephine.” Victoria’s parents lived across the road from her and young Calvin Coolidge, and Coolidge described them as “prosperous farmers.”

Victoria Coolidge’s Appearance

Coolidge wrote the following of his mother’s physical appearance:

She was of a very light and fair complexion with a rich growth of brown hair that had a glint of gold in it. Her hands and features were regular and finely modeled. The older people always told me how beautiful she was in her youth.

Calvin Coolidge describing his mother’s appearance

Victoria Coolidge as a Mother

Coolidge noted that his mother “was practically an invalid ever after I could remember her.” Despite her infirmities, however, she “used what strength she had in lavish care upon me and my sister, who was three years younger.”

Coolidge’s younger sister, Abigail Grace Coolidge, died of what was likely appendicitis five years after his mother died. A bit later in the book, Coolidge noted with regret that appendicitis came to be understood in 1890, just a few short years after his sister died of what was then a mysterious ailment. Of his sister, he wrote: “The memory of the charm of her presence and her dignified devotion to the right will always abide with me.”

Calvin Coolidge On His Mother’s Nature and Sensibilities

After describing his mother’s family, appearance, and care for him and his sister, Coolidge endeavored to do what he said was impossible – to adequately describe his mother. He began his attempt:

There was a touch of mysticism and poetry in her nature which made her love to gaze at the purple sunsets and watch the evening stars.

Coolidge continued:

Whatever was grand and beautiful in form and color attracted her. It seemed as though the rich green tints of the foliage and the blossoms of the flowers came for her in the springtime, and in the autumn it was for her that the mountain sides were struck with crimson and gold.

Additional Thoughts

I was inspired to write this article principally because of Coolidge’s beautiful description of his mother’s nature and sensibilities. That his mother appreciated the sunsets and stars was not merely because she liked pretty things, but rather because of something intrinsic to her nature – “a touch of mysticism and poetry.” This attracted her to all things that were beautiful in both form and color. Despite being an invalid, she was keenly aware of the changes in the seasons and each season’s distinct peculiarities. To Coolidge, who loved his mother dearly, it seemed as if the seasons responded to her, rather than her noting the seasons.

This passage made me thing of a later, seemingly unrelated section of Coolidge’s autobiography wherein he described his college philosophy class, taught by Charles E. Garman. In describing what he took from Garman’s courses, Coolidge wrote the following:

Every reaction in the universe is a manifestation of [God’s] presence. Man was revealed as His son, and nature as the hem of His garment, while through a common Fatherhood we are all embraced in a common brotherhood. The spiritual appeal of music, sculpture, painting and all other art lies in the revelation it affords of the Divine beauty.

(Emphasis added.)

Victoria Coolidge’s Final Day and Calvin’s Memories

Coolidge wrote that when his mother knew that her end was near, she called him and his sister to her bedside to give her final parting blessing. Of the aftermath, Coolidge wrote:

In an hour she was gone. It was her thirty-ninth birthday. I was twelve years old. We laid her away in the blustering snows of March. The greatest grief that can come to a boy came to me. Life was never to seem the same again.

That, for Coolidge, was a moment when his life changed in an ineffable way. He wrote: “It always seemed to me that the boy I lost was her image.” Coolidge would, according to the Calvin Coolidge Presidential Foundation, carry ‘a small case containing her portrait with him for the rest of his days.”

Final Thoughts on the Colors of Coolidge’s Recollections

From Calvin Coolidge’s description, we learn of an impressive young woman with a keen sense of beauty and aesthetics. She was no less impressive in character, perhaps, than her son who would go on to ascend to his country’s highest office. Victoria Coolidge left a strong impression on young Calvin in the twelve years they were together – and his childhood experiences gave him the foundation to achieve great things as an adult. It is because of those accomplishments that he was in position to tell a large contemporary audience and posterity about his mother, who would have otherwise been long forgotten. As hard as it may have been for him to write about it, those who read it should be thankful that he did.

Victoria Coolidge’s memory lives on in the evergreen leaves of her son’s post-Presidential autobiography, resplendent in its perennial viridity.