244 years ago to tomorrow, the United States declared its independence from the British Empire. 147 years ago to tomorrow, John Calvin Coolidge, who would go on to become the 30th President of the United States, was born in Vermont. Given the concurrence of these two July 4 events, I thought that it would be altogether fitting and proper to offer a July 4 Coolidge speech. However, rather than examine one of his many excellent speeches as president, we will instead look at a speech that Coolidge delivered when he was the 46th Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts in 1918, on the subject of a story of friendship between the United States and Japan.

Basic Background on Coolidge

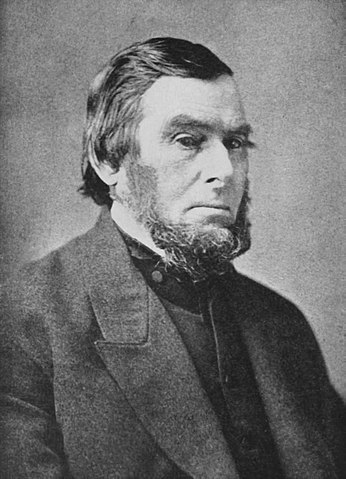

Vice President Calvin Coolidge became President Calvin Coolidge on August 2, 1923, on the occasion of the untimely death of President Warren Harding. Before Coolidge was sworn in as Vice President in 1921, he had spent the prior decade serving in various elected positions in Massachusetts.

From January 6, 1916 to January 2, 1919, Coolidge served as the Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts. He would vacate that position in 1919 when he was elected Governor. Today, however, we will look at a speech that he delivered as Lieutenant Governor on July 4, 1918, his own 45th birthday and the 142nd birthday of the United States.

Background for Coolidge’s July 4, 1918 Remarks in Fairhaven

On July 4, 1918, Lieutenant Governor Coolidge delivered remarks from Fairhaven Massachusetts. Fairhaven had been the home of Captain William H. Whitfield, an enterprising sea captain who lived from November 11, 1804 through February 14, 1886.

In 1841, circumstances aligned for Captain Whitfield to play a major role in United States-Japan relations. The following story is summarized from the website of the Fairhaven Office of Tourism.

A Fateful Encounter

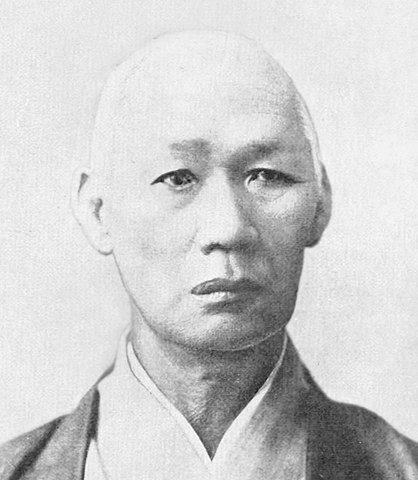

A Japanese boy by the name of Manjirō Nakahama set off on a fishing expedition at the age of 13 in 1841. Unfortunately, he and his three companions were caught on a storm and eventually shipwrecked on the uninhabited island of Tori Shima. After surviving alone for six months, they were discovered by Captain Whitfield, who was in command of the whaleship John Howland. Captain Whitfield rescued the stranded Japanese fishermen and eventually set three of them ashore at the Sandwich Islands, which now compose Hawaii.

Captain Whitfield Brings Manjirō Nakahama to Fairhaven

Manjirō was initially imprisoned upon his return to Japan because it was the policy of the Japanese Government to prohibit people from leaving. Manjirō would soon be freed, and his experience in Fairhaven, Massachusetts, would turn out to play an important role in world history.

A couple years after Manjirō’s return to Japan, Commodore Matthew Perry made several expeditions to Japan to compel it to open trade relations. Manjirō, who had initially been detained due to his time in the United States, suddenly became valuable because of his knowledge of the United States and the English language. The article informs us that “Manjirō rose to prominence in Japanese governmental circles and was made a samurai.” In addition to encouraging Japan to implement close relations with the United States, the article notes that “[h]e has also been credited with introducing the necktie to Japan.”

Manjirō went on to write “A Short Cut to English Conversation,” which the article states “became the standard book on practical English [in Japan] at that time.” He was sent on two diplomatic missions to the United States. In 1870, on the second of his missions, he returned to Fairfield and spent the night in Fairfield with Captain Whitfield and his wife.

The Occasion for Coolidge’s Remarks

By July 4, 1918, Captain Whitfield and Manjirō had both long since passed away, the former in 1886 and the latter in 1898. However, for the occasion of the 1918 Independence Day, Fairhaven was the recipient of a visit by Ishii Kikujirō, then serving as a special envoy to the United States on behalf of the Japanese Emperor. As we will see from Coolidge’s speech, Ishii was visiting Fairhaven to present the town with a samurai sword on behalf of Manjirō.

Coolidge’s July 4 Remarks in Fairhaven, Reprinted in their Entirety

Upon Calvin Coolidge’s becoming Governor of Massachusetts, his political speeches were collected in Have Faith in Massachusetts: A Collection of Speeches and Messages. You may find a link to the speech here in the Project Gutenberg copy of the collection. It is also available for free for Kindle.

Below is Calvin Coolidge’s July 4, 1918 speech in its entirety, reprinted from Have Faith in Massachusetts:

The Speech

We have met on this anniversary of American independence to assess the dimensions of a kind deed. Nearly four score years ago the master of a whaling vessel sailing from this port rescued from a barren rock in the China Sea some Japanese fishermen. Among them was a young boy whom he brought home with him to Fairhaven, where he was given the advantages of New England life and sent to school with the boys and girls of the neighborhood, where he excelled in his studies. But as he grew up he was filled with a longing to see Japan and his aged mother. He knew that the duty of filial piety lay upon him according to the teachings of his race, and he was determined to meet that obligation. I think that is one of the lessons of this day. Here was a youth who determined to pursue the course which he had been taught was right. He braved the dangers of the voyage and the greater dangers that awaited an absentee from his country under the then existing laws, to perform his duty to his mother and to his native land. In making that return I think we are entitled to say that he was the first Ambassador of America to the Court of Japan, for his extraordinary experience soon brought him into the association of the highest officials of his country, and his presence there prepared the way for the friendly reception which was given to Commodore Perry when he was sent to Japan to open relations between that Government and the Government of America.

And so we see how out of the kind deed of Captain Whitefield, friendly relations which have existed for many years between the people of Japan and the people of America were encouraged and made possible. And it is in recognition of that event that we have here to-day this great concourse of people, this martial array, and the representative of the Japanese people—a people who have never failed to respond to an act of kindness.

It was with special pleasure that I came here representing the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, to extend an official welcome to His Excellency Viscount Ishii, who comes here to present to the town of Fairhaven a Sumari sword on behalf of the son of that boy who was rescued long ago. This sword was once the emblem of place and caste and arbitrary rank. It has taken on a new significance because Captain Whitefield was true to the call of humanity, because a Japanese boy was true to his call of duty. This emblem will hereafter be a token not only of the friendship that exists between two nations but a token of liberty, of freedom, and of the recognition by the Government of both these nations of the rights of the people. Let it remain here as a mutual pledge by the giver and the receiver of their determination that the motive which inspired the representatives of each race to do right is to be a motive which is to govern the people of the earth.

Examining Coolidge’s Remarks

Below, I will offer my own assessment of Coolidge’s July 4 remarks in Fairhaven.

Manjirō’s Sense of Duty

Then-Lieutenant Governor Coolidge placed an interesting focus on Manjirō’s sense of duty. In his speech, he states that Manjirō went back to Japan both because he was homesick and also because he wanted to see his aging mother. “He knew that the duty of filial piety lay upon him according to the teachings of his race, and he was determined to meet that obligation.” From this, Coolidge suggested that we could all glean something: “Here was a youth determined to pursue the course which he had been taught was right.” Coolidge found Manjirō’s sense of duty all the more notable in that he faced great dangers as “an absentee from his country under the then existing laws…”

The Significance of Manjirō’s Contributions

As we know, Manjirō was initially punished upon his return to Japan before the Japanese Government realized that his experiences made him quite valuable. Coolidge described Manjirō as “the first Ambassador of America to the Court of Japan,” and noted, as we recounted earlier, that “his extraordinary experience soon brought him into the association with the highest officials of his county, and his presence there prepared the way for the friendly reception which was given to Commodore Perry…”

Captain Whitfield’s Kindness

None of this would be possible, Coolidge observed, without “the kind deed of Captain Whitfield…” It was all because Captain Whitfield went out of his way to rescue four shipwrecked young men from Japan and acquiesced to Manjirō Nakahama’s request to travel to America that both the United States and Japan were to benefit. Describing the Japanese people as “a people who have never failed to respond to an act of kindness,” Coolidge traced the then-positive trans-Pacific U.S.-Japan relations to a series of reciprocated kind deeds .

Tying the Themes Together

The final section of Coolidge’s remarks focused on the visit of Ishii. We learn from the speech that Ishii came bearing a samurai sword on behalf of Manjirō. Coolidge opined that while the samurai sword “was once the emblem of place and caste and arbitrary rank,” it meant something different as a gift to Fairhaven. In this context, Coolidge said that the sword was given new significance because of the humanity of Captain Whitfield and the sense of duty of Manjirō. Infused with this meaning, the sword would “be a token not only of the friendship that exists between two nations but a token of liberty, freedom, and of the recognition by the Government of both these nations of the rights of people.”

Final Thoughts

At the time Coolidge delivered his Independence Day remarks in Fairhaven, the United States and Japan were on the same side in the First World War. Although the War would be over in several months, young American men were still fighting and dying in the blood-soaked trenches of Europe.

As we know, the friendship between the United States and Japan would disintegrate with the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, only to be rebuilt following the American victory in World War II and the subsequent occupation of Japan.

Every good relationship has hiccups, and I suppose it suffices to say that the relationship between the United States and Japan had a rather large hiccup in the form of a brutal war started by Japan and finished by the United States. While that led to the United States reorganizing Japanese society and re-contextualizing the relationship between the two nations, it does not vitiate all that came before. Captain Whitfield’s kindness and Manjirō Nakahama’s decision to return to Japan helped launch decades of positive relations between the two countries. That history perhaps played a role in the ultimate restoration of United States-Japanese relations after General Douglas MacArthur’s fruitful work during the post-war occupation.