Yesterday (October 1, 2021), I covered Autumn, a poem published in the October 1, 1898 issue of The Girl’s Own Paper – a British paper for young girls that ran from 1880 to 1956. Today I return to that issue of the nineteenth century magazine not for poetry, but instead for an article titled Invalid Cookery. The magazine kindly listed a number of recipes for sick people. Some of the recipes are acceptable. Other recipes are more akin to the “coffee fruit punch” that I covered in fall 2020. Below, I will list each recipe for the convalescent and assess whether the end product would aid in recovery or make a healthy person (i.e., me) sick.

You can follow along with all of the Invalid Cookery recipes in the original magazine.

Beef Tea

The first recipe in Invalid Cookery is an old standby – beef tea.

The article listed the following ingredients: “One pound shin of beef, one pint of water, a little salt, a few drops of lemon juice.”

Then it provided preparation instructions:

Take away all skin and fat from the beef, and shred it finely, putting it as you do so into a jar with the water, lemon juice, and salt; put on the lid and let it stand half an hour; stand the jar on a dripping tin with cold water, and put it in the oven for two hours. Stir up, pour off against the lid and remove any fat with kitchen paper.

When I was convalescing after abdominal surgery a few years ago, my diet was limited. I partook in beef and chicken tea with lemon. It was good. I had broth from the box. This recipe would have not comported with my all-liquid diet, but it does sound much fancier than what I went with. I certainly would not want to prepare this beef tea, nor would I leave beef sitting out in a jar of water for any amount of time. But the end product is likely acceptable.

Quick Beef Tea

Making regular beef tea in the Invalid Cookery way would be a bit of a production. Perhaps recognizing that, the magazine offered a quicker alternative. The ingredients for quick beef tea are the same as for regular beef tea, but the preparation method is different:

Cut the meat up small and let it stand in water for twenty minutes; put in a saucepan and let it just heat through, pressing the pieces against the side with a wooden spoon.

This too is likely acceptable in taste – with some of the same caveats I noted for the slow beef tea. I would just make sure to cook that beef through. I, like former Presidents Grant and Trump, only partake of beef cooked very well.

Raw Beef Tea

I shudder.

Using the same ingredients as the previous beef tea and preparing it in the same way as the first beef tea, cooks for the sick are instructed to let the end product stand for two hours, stir it, and pour off the liquid.

Now raw beef tea is actually cooked. But you never know with these beef people. I had a debate with a friend in high school. I said that steak should crumble when it is touched with a fork. He said his steak should come out on a leash and say “moo.”

Terrifying.

The raw beef tea is the only one of the three beef teas that I could have had in the aftermath of my surgery. But you cannot call it raw beef tea. It needs a different name.

Nevertheless, the end product would be acceptable.

Strengthening Broth

The method for preparing strengthening broth is the same as for preparing regular beef tea. The difference is that it includes mutton and veal in addition to beef. I do not eat mutton or veal. While I am sure the “strengthening broth” tastes fine, why does one need three kinds of meat? This sounds needlessly complicated.

Mutton Broth

Having had a taste of mutton in the previous recipe, we now go all in on mutton.

Ingredients for mutton broth: “One pound of scrag of mutton, one pint of water, two ounces of pearl barley, salt, a blade of mace, a little chopped parsley.”

Preparation method: “Cut as much fat as possible from the meat; cut the meat up small and chop the bones; put the meat and bones in a saucepan with the water, mace, salt and barley, which should be blanched (see “Odds and Ends”). Put on the lid and simmer very gently for two hours. Stir up and pour off against the lid into a basin; stand in cold water in a larger basin for the fat to rise, skim well, re-heat and add a little chopped and blanched parsley.”

Nothing about sheep screams (or “baas”) dinner to me. That does not change when I am sick. I will leave the mutton broth for others.

Essence of Beef

I am on guard after seeing the words “raw” and “beef” together. But maybe this will be fine.

The ingredients are listed as follows: “One pound of shin of beef, two tablespoonfuls of water, a little salt, a few drops of lemon juice.”

I never had beef essence. It is probably good if cooked enough. Is this enough? Four hours is a long time, but the beef is in a jar. I never boiled or broiled a jar of beef. I would check it to make sure it was really cooked all the way through. No red, even if I am only having the essence. Let us go with six hours just to be on the safe side.

Raw Meat Sandwiches

Oh no.

We do not have a list of ingredients. Just a recipe. It is as if the ingredient list is too horrifying to write out.

Preparation method: “Scrape a little raw beef finely and put a little piece in the middle of some tiny squares of thin bread, cover with other squares and press the edges tightly together with a knife so that the meat may not show.”

I would say that I am going to be sick.

But if I became sick, would there be a non-zero chance that someone would try to give me a raw meat sandwich?

Note that the recipe instructs innocent readers of this magazine for young girls to ensure that the raw beef does not show. Is this actually a prank? Are they teaching unwitting girls how to prank the sick?

I feel like having a pint of coffee fruit punch to make me forget about raw beef sandwiches. I am not going to do that, however.

Meat Custard

Let us hope the beef is cooked this time.

For raw beef custard, you will need one egg and half a gill of beef tea.

In order to prepare the beef custard, one must “beat the egg and beef tea together and steam in a large buttered tea cup for twenty minutes.”

This sounds like a good dish. What a difference a change in recipe makes after the previous disaster.

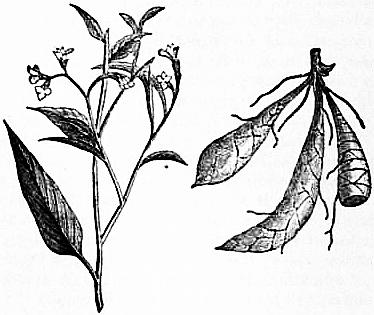

A Cup of Arrowroot

I wonder what the main ingredient is going to be…

The list of the ingredients is as follows: “Half a pint of milk, one ounce of arrowroot, one ounce of castor sugar.”

You prepare the ingredients for the sick as follows: “Mix the arrowroot smoothly with a little cold milk; boil the rest of the milk and stir in the arrowroot; stir and boil well, taking care it does not burn.”

I never had arrowroot, but this sounds like it may be good. Maybe I will try a version of it and report back.

Cornflour Soufflée

It is nice to see this magazine go through so much effort to make up for the [redacted] meat sandwich.

For cornflour soufflée, one needs: “Half a pint of milk, one egg, one ounce of cornflour, one ounce and a half of castor sugar, one bay leaf.”

Bay leaf? I digress. The mixture is prepared as follows: “Mix the cornflour smoothly with a little cold milk; boil the rest with the bay leaf and sugar; stir in the cornflour and let it thicken in the milk; separate the white and yolk of the egg and beat in the yolk when the cornflour has cooled a little; beat the white very stiffly and stir it in very lightly. Pour into a buttered pie-dish, and bake in a good oven until well thrown up and a good light brown colour.”

I would omit the bay leaf, but this otherwise sounds decent.

Custard Shape

For custard shape, one needs: “Half a pint of milk, two eggs, quarter of an ounce of gelatine, two ounces of castor sugar, vanilla.”

In order to prepare the custard, one must: “Beat up the eggs with the sugar and milk; pour into a jug, stand in a saucepan of boiling water and stir with the handle of a wooden spoon until it thickens; dissolve the gelatine in it, flavoured with vanilla, pour into a wetted mould and turn out when set.”

I do not always like the texture of custard, but this dish sounds good. The good sick food trend continues.

Sponge Cake Pudding

This is an interesting-sounding recipe.

In order to make sponge cake pudding, one will need: “Two stale sponge cakes, three eggs, half a pint of milk, two ounces of castor sugar, a piece of thin lemon rind.”

The preparation method has a few steps: “Boil the milk with the rind and the sugar; let it cool a little and add the eggs well beaten; cut the sponge cakes in pieces and lay them in a buttered tin, pour the custard over and bake gently until set. Turn out and set cold.”

I do not think I have ever had anything quite like this. It probably tastes good. Acceptable again.

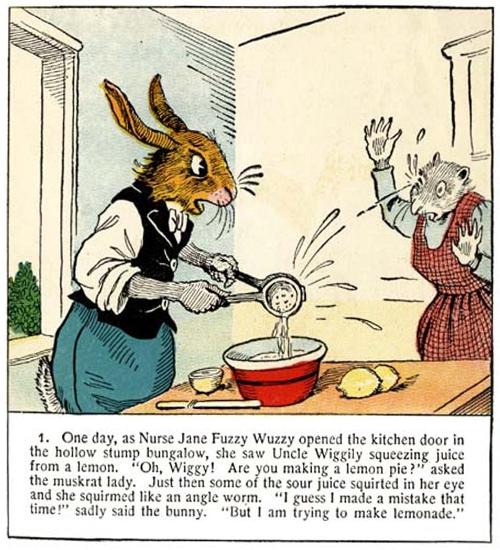

Lemonade

An old staple. Or is it?

The ingredients for this lemonade are innocuous enough: “Two large lemons, one quart of water, a quarter of a pound of castor sugar.”

The preparation method, however, is a bit more complicated than what makes it to many of the lemonade stands run by kids these days: “Pare the lemons very thinly, so that the rind is yellow both sides, put the rind with the sugar and the lemon-juice in a jug, pour boiling water on it, and let it stand till cold, strain and use.”

However you get to the end result – this is certainly lemonade. I have no problem with lemonade, but I think tea with lemon may be better for the sick. Why was that omitted. It is not as if tea was something that the British were unfamiliar with. Not to mention – I recall covering one story wherein lemonade did not a gree with a sickly young boy.

Barley Water

This is the most exciting recipe name thus far.

For barley water, one will need: “Two ounces of pearl barley, one quart of water, a small piece of lemon rind, one ounce and a half of castor sugar.”

To prepare barley water, one must: “Blanch the barley; put it in a saucepan with the lemon-rind and sugar, and simmer gently one hour. Strain and use.”

It is hard to get too excited one way or another about barley water. The end result of this recipe is likely decent. I am just happy to have avoided any disasters since the raw beef.

The next recipe is the last. Did they save the best for last?

Toast and Water

Toast with water sounds good for the sick. But what precisely is toast and water? The magazine skipped the ingredient list and moved straight to the recipe.

Toast a piece of bread until nearly black. Put it in a jug and pour cold water on it.

I have but one question.

Why?

Why would anyone do this?

What’s more, we had meat teas and meat essence recipes in this article. Why not have the toast with one of those? Toast in water? If this was once a thing, it is one of those things that is best left in the past.

Water toast is, however, much better than raw beef sandwiches.

Conclusion

I hope you enjoyed the study of invalid cookery from late-nineteenth century Britain. Taking a non-toast-glass-half-full view of things, the majority of the recipes ranged from acceptable to good. There were enough presentable recipes before the toast water to almost make me forget about the raw beef sandwiches. The toast water actually helped me forget about the raw beef sandwiches. I am not grateful enough to it to try toast water, but grateful nevertheless.

Consider the recipes some inspiration for ideas for what to eat the next time you or someone you are in position to cook for becomes sick.