I came across an interesting article by Mr. Guy Winch, a licensed psychologist and author, titled Video Games Can Boost Emotional Health and Reduce Loneliness, published on Psychology Today on December 6, 2019. One specific passage in Mr. Winch’s article interested me, and I quote it in its original context:

But while video games and gaming can have detrimental impacts in some contexts, what gets lost amidst the psychopathology-skewed headlines is that they can also provide significant benefits to our emotional health and well-being. In fact, game developers are now designing games with the specific purpose of addressing psychological issues and boosting emotional health.

Guy Winch (emphasis added).

For purposes of the instant article, I will accept as true that video games, like other forms of art and entertainment, can provide benefits to players as a general matter – without commenting specifically on the parameters of “our emotional health and well-being.” Setting aside the broad thesis, I was most interested in the word choice employed by Mr. Winch in the second sentence of the above excerpt. I repeat it below with additional emphasis

[G]ame developers are now designing games with the specific purpose of addressing psychological issues and boosting emotional health.

Guy Winch (emphasis added).

Is this a good thing? On the surface, the idea of designing a video game to benefit the health of players sounds good. But on what foundation should a video game rest? What is the ideal purpose of a video game, and how is that purpose best conceived and implemented?

After considering the issue, I concluded that I had some issues with Mr. Winch’s quote. While I do not know whether it was his intention to praise the idea of designing a game with the primary purpose of addressing psychological issues and boosting emotional help, that is how I read the passage in the context of the article. To the extent one may suggest that this would be a good primary purpose in creating a game, I opine that this suggestion would be made in error.

(Important Note: Mr. Winch uses two games as examples. The first is Ms. Cornelia Geppert’s 2013 Sea of Solitude and the second is an un-named multi-player mobile game. I make clear here that nothing in this article is, or should be read as, a commentary on either Sea of Solitude or the un-named mobile game. I had never heard of either until reading Mr. Winch’s article, and it is not my intention to offer opinions on games with which I am not familiar. I will add that notwithstanding the passage by Mr. Winch that I am focusing on, his description of Sea of Solitude discusses its merits as an interesting and engaging game in addition to how it may positively affect the emotional health of those who play it. My article assesses the implications of Mr. Winch’s quote alone, not his examples.)

In an earlier article, I suggested that a video game should, ideally, be “engrossing but not excessively addictive.” That is, good game design should result in players engaging meaningfully, rather than compulsively, with the game. Working from the assumption that games can positively benefit the health and psychological states of players, these benefits are downstream of good game design. No matter how noble a game designer’s intentions are, a game will fail to have a distinctly positive impact on a player if it is not engrossing. It would similarly fail to leave an impact if its purpose is to cause the player to play the game as a habit. Games may advance compelling views about how to live life and promote positive mental health. Moreover, as Mr. Winch noted in the second example in his article, games may encourage community among players. I will add without discussing further that there is a growing number of games which seek to offer educational benefits (let no one say that the classic Freddi Fish games are not engrossing). But a game that is not engaging at its core will likely achieve none of these secondary objectives.

The primary purpose of a game best conceived should be to be a good game, designed in both form and function to be engrossing in a positive way from the end-player’s perspective. Games need not all aspire to the same heights. There are many more games of the hour to play than games for all time – and there is nothing wrong with that. So long as the designer first contemplates how to make a meaningfully engrossing game for the player, he or she is off to a good start. Lofty ideals attached to a dull game are structures built on a foundation of sand. But lofty ideas attached to an engaging game can reach the player.

I will use two examples from games that I have played to illustrate my point. In order to tie the examples in to past content, I will use Persona 4 and Pokémon Red and Blue, games which I have written about here on site.

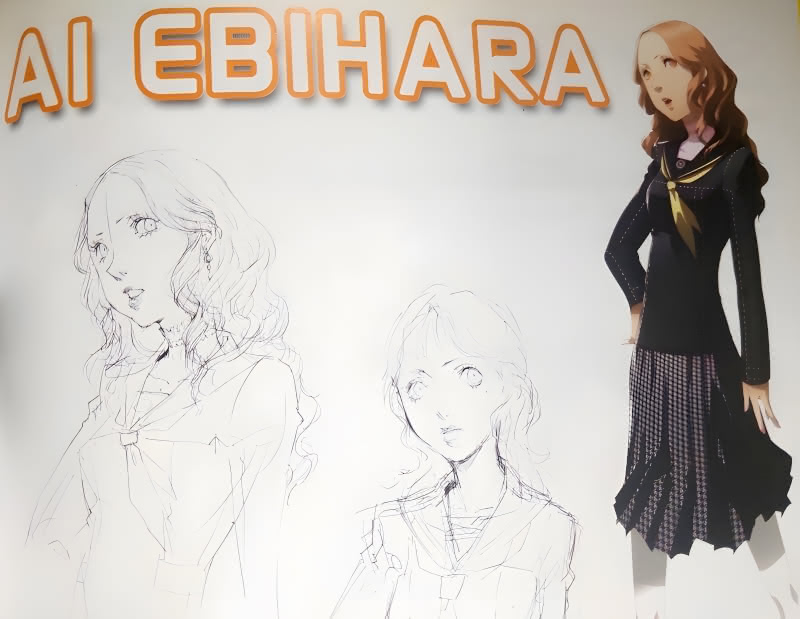

The Persona series consists of lengthy Japanese role-playing games. The three most-recent entries, Persona 3, 4, and 5, are notable for featuring social links, wherein the protagonist can befriend various in-game characters. I discussed an event involving two of the better social links in Persona 4 in an earlier article. My favorite social link in the three modern Persona games is Persona 4’s Ai Ebihara (see external analysis), who is a second high school student (same age as the player character) who begins her story arc as a vain and unpleasant character. If the player character persists in getting to know her notwithstanding her myriad faults, he learns the reasons behind Ai’s behavior. The arc is notable for being un-notable, Ai’s problems and insecurities are both mundane and very human. Her character’s resolution, too, is normal, a proverbial turning over a new leaf rather than a full-blown resolution of life and all its problems (see a visual novel with a similar conclusion). Playing through the link and carefully considering its message could benefit players. In understanding Ai, one sees a study of one unfortunate manifestation of intense insecurity. In getting to understand Ai, one sees the power of being willing to consider whether there is something more to a person than mere outward appearances. There are lessons for, and regarding, people who share Ai’s insecurities and fear of being misunderstood, even in cases where these fears manifest in far less unpleasant ways than they do in Ai early in her story arc. However, the reason why this meaningful link may have an impact on some people who read it is that it comes as part of a genuinely engaging and well-designed game. Were a player to find Persona 4 boring or insipid, it is unlikely that he or she would take the time to learn Ai’s story. It is precisely because Persona 4 is an excellent piece of digital art that a player (1) plays far enough into the game to undertake Ai’s social link; and (2) may have faith that the investing time in the link will be a worthwhile endeavor.

(I will note that there additionally is some interesting meta commentary on the interaction of game-play incentives with Ai’s social link which also implicate the fact that Persona 4 is genuinely engrossing and fun to play, but I will set those aside for a future article.)

Mr. Winch’s second example of a game with positive benefits concerned games that foster community and interaction. The classic example of this from my childhood is Pokémon Red and Blue. Released in the United States shortly before playing games online became commonplace, multi-player in Pokémon was achieved by physically linking two Game Boy consoles with a link cable. According to an interview with the producer of Pokémon Red and Blue, Mr. Shigeki Morimoto, there was some debate as to whether or how multiplayer battling should be implemented in Pokémon, and it was almost omitted before the original Japanese release of Pokémon Red and Green in February 1996. To be sure, trading Pokémon was intrinsic to the original design, but multi-player battling was not. Both trading and battling ultimately played a role how Pokémon Red and Blue were able to encourage human interactions between children who had the games.

There was plenty of debate surrounding the Pokémon phenomenon in the United States 1998 and 99 that we need not delve into or re-litigate here. We have already accepted in this article that games can have positive effects, and I will submit that the original Pokémon games had a positive effect of encouraging players who enjoyed the games to interact with one another in person, whether through trading to collect Pokémon or battling to test their skills. In contrast to multi-player games in the internet era (including recent Pokémon games), Pokémon Red and Blue encouraged local, human engagement in a way that was uniquely possible when it was released. But while Game Freak’s clever use of the link cable was necessary to many of Pokémon’s social benefits, it was not sufficient – the technology alone did not complete the circuit. Had the primary purpose in designing Pokémon been to encourage players to interact with one another via link cable play, that purpose would not have been realized. Pokémon succeeded because that element came with a genuinely engrossing game which inspired the imagination.

I submit the foregoing as my own addendum to Mr. Winch’s quote on games designed to induce positive secondary benefits. Games may well have positive effects on players, and a good game designer does well to cause those effects through his or her game, but the positive effects will only be realized in the real world if the game to which they are attached is engrossing. What makes a game engrossing as opposed to a work of film, literature, music, or even a visual novel may be unique, but the requirement that the fundamentals of the work must be sound in order for the work to leave a meaningful impression on those who engage with it is true across the myriad artistic forms.