I published an article in June 2020 on the philosophy of the “man with the hose” washing Brooklyn sidewalks with copious (and excessive) amounts of water. That article came to mind when I read about a “novel garden sprinkler” in the December 14, 1878 issue of Scientific American. We will cover an article titled An Improved Garden Sprinkler, which discussed the Hodel & Stauber’s Garden Sprinkler.

Let us examine the sprinkler further.

“An Improved Garden Sprinkler”

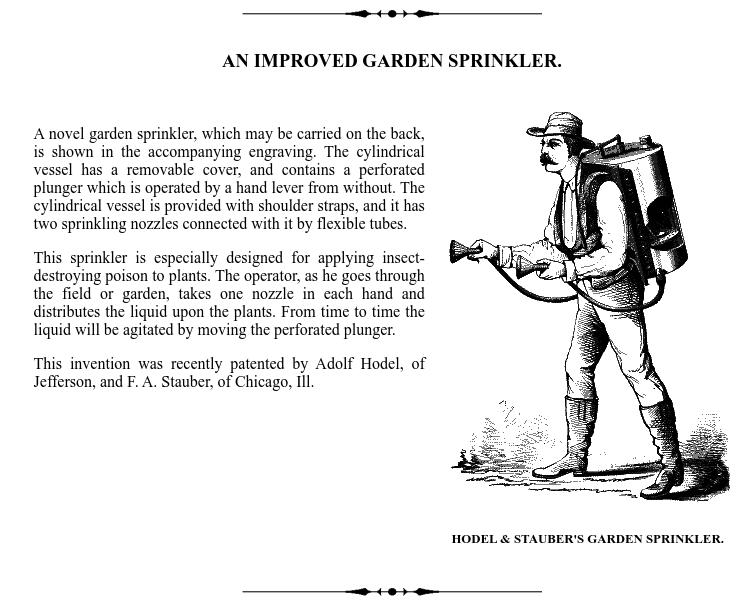

The Scientific American article explained how the garden sprinkler would work which you will find in the screen capture below.

According to the description, the sprinkler would work as follows:

The cylindrical vessel has a removable cover, and contains a perforated plunger which is operated by a hand lever from without. The cylindrical vessel is provided with shoulder straps, and it has two sprinkling nozzles connected with it by flexible tubes.

The end purpose of the new garden sprinkler, which was patented by Adolf Hodel of Jefferson, Illinois, and F.A. Stauber, of Chicago, Illinois, was “for applying insect-destroying poison to plants.” In order to accomplish this task, “[t]he operator … takes one nozzle in each hand and distributes the liquid upon the plants.”

The Hodel & Stauber’s Garden Sprinkler Man

As I noted, I decided to write about the “improved garden sprinkler” because it reminded me of my man-with-the-hose article. Having assessed the description of the sprinkler and studied the terrific engraving of a man operating it in Scientific American, I think that it is unlikely one using this invention could achieve the same levels of tranquility and philosophical insight as the wasteful man-with-the-hose. I reach this conclusion for two reasons.

I posed the following question to begin my specious man-with-the-hose study:

It has been asked why the-man-with-the-hose uses so much water. There must be a point beyond which the ground can become no cleaner.

Nicholas A. Ferrell (article)

The consequences of over-watering the sidewalk are minimal for all matters except for mosquito breeding. Conversely, I have to think that there is a point when using too much insecticide on plants may be harmful to people if not to plants.

Furthermore, the Hodel & Stauber’s Garden Sprinkler, well designed as it may be, does not look conducive to meditating on the meaning of the philosophy of Thales and Heraclitus. It looks a bit heavy. Even if it is not too heavy, it does not look like something that one would want to wear longer than necessary to complete a task. Suffice it to say, but wielding a garden hose is more amenable to pondering the nature of things than lugging a contraption full of insecticide on one’s back.

Returning to the engraving of the man with the Hodel & Stauber’s Garden Sprinkler, I think it more likely that his thoughts are fixated solely on attending to the task at hand in order that he can remove the garden sprinkler from his back than achieving the contentedness of the contemporary man-with-the-hose in Brooklyn, New York.