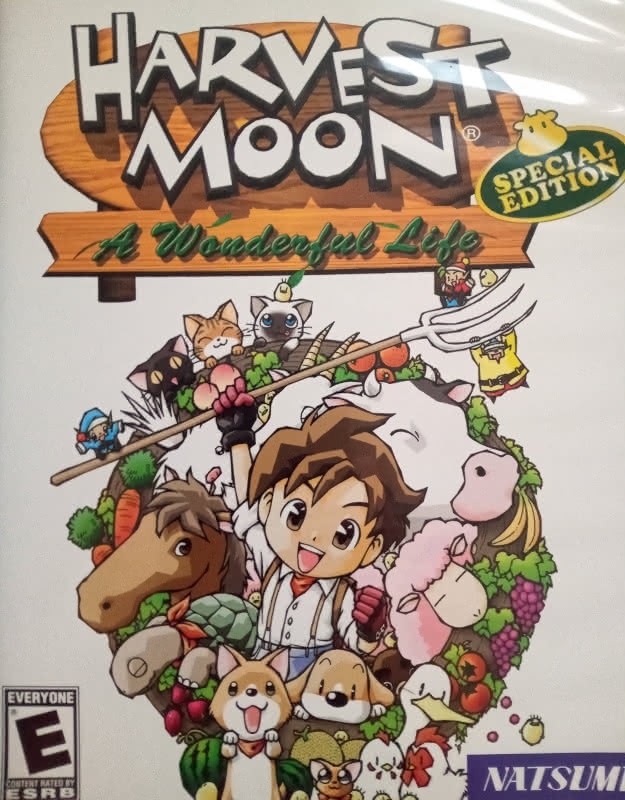

Harvest Moon: A Wonderful Life, an entry in the long-running Harvest Moon (now “Story of Seasons”) series, was released for the Nintendo GameCube in North America on March 16, 2004. I obtained my own copy in June 2004, but that is neither here nor there. The game made one cameo appearance in my article about the origin of the forget-me-not flower’s name because A Wonderful Life takes place in the fictional Forget-Me-Not Valley. But the purpose of this article is not to tell my own Wonderful Life story; it is to briefly discuss a quote from a 2004 review of the classic farming game, an excerpt of which features as the title of the instant article. Before progressing to the review, however, a short introduction to Harvest Moon: A Wonderful Life is in order to put the main point of the article in context.

(If you are already familiar with Harvest Moon: A Wonderful Life, feel free to skip to the last section.)

What is Harvest Moon: A Wonderful Life?

(A Note on Names: The Harvest Moon/Story of Seasons games come from Japan, where it is the Bokujō Monogatari series. When the Bokujō Monogatari games first came to the United States, they were localized by the publisher Natsume as Harvest Moon. However, the Japanese developer, Marvelous Interactive, switched publishers in 2013, but Natsume retained the Harvest Moon trademark. Thus, subsequent Bokujō Monogatari games, including an upcoming remake of A Wonderful Life, are localized as Story of Seasons instead of Harvest Moon. Natsume releases its own Harvest Moon games, but any and all discussion of the series in this article pertains only to the games developed by Marvelous Interactive.)

The main-line Harvest Moon/Story of Seasons series features 22 entries, of which Harvest Moon: A Wonderful Life was the eighth. All of the Harvest Moon/Story of Seasons games feature the player running a farm. Most, but not all, of the main-line Story of Seasons allow the player to marry and, in some cases, start a family. A Wonderful Life was, and remains to this day, a unique entry in the series because its primary focus is on the family. The player is required to marry one of three bachelorettes (four in a remastered PlayStation 2 version which was released in North America in 2005) in the first chapter of the game and the subsequent chapters follow the couple and their child through different stages of life. While A Wonderful Life is not a dark game, it features a heavier atmosphere and themes than modern entries in the series, although some of its themes are in line with the console entries that preceded it. Both the protagonist and the three marriage candidates (in the original GameCube version) ranged in age from 26-30, which is a few years older than many of the characters appear to be in some of the other early Harvest Moon entries. (The PlayStation 2 version introduced an 18-year old bachelorette and a subsequent re-mastered version allowed the player to choose a female protagonist which made several bachelors available for marriage.)

Edutaining Kids’ Review of A Wonderful Life

A website called Edutaining Kids reviewed A Wonderful Life in July 2004 (archived page). The review is solid and agreeable as a whole, noting the games’ significant strengths while also acknowledging that A Wonderful Life, like all of the extant Harvest Moon games at the time, is an acquired taste. I will reserve my full thoughts on the review since I may have my own to share in the future, but Edutaining Kids’ conclusion caught my attention for an astute insight…

Being Engrossing Without Being “Excessively Addictive”

One tester was pleased that Harvest Moon is engrossing but not excessively addictive. This way, he feels that the game lasts longer because he doesn’t play it obsessively. He insists, nevertheless, that it is very appealing to play.

Edutaining Kids Tester on Harvest Moon: A Wonderful Life

I find the phrase “engrossing but not excessively addictive” to be very interesting. To be “engrossing” is to be “monopolizing” or “absorbing” (credit Webster’s Second). A game worth playing on its merits is necessarily engrossing in that its aesthetic qualities absorb the attention of the player and cause the player to carefully attend to it. To be “addictive” in the sense that the tester used the term necessarily carries with it other connotations. One who is “addicted” in this sense is “habituated,” “prone,” and “attached” (credit again to Webster’s Second – Note “addiction” does also have positive uses, albeit they are not common). Addiction, in a negative sense, is an inherently passive concept that encompasses a person doing something habitually or being prone or inclined to a certain activity to the exclusion of others rather than meaningfully engaging with it in a positive way.

The environment for video games in 2004 was quite a bit different than it is today. The games that commanded people’s time were most often games that were purchased once to be enjoyed going forward. A Wonderful Life contains no downloadable extra content, much less the micro-transactions that characterize less savory farming affairs like FarmVille. To be sure, some games of the era, such as the early massively multiplayer online games and games designed primarily for arcade play had revenue models that depended on habitual players. But a game with a one-purchase-one-time model is not incentive to be addictive (in the negative sense) by design.

The tester who offered the “engrossing but not excessively addictive” assessment of A Wonderful Life appears to have had some concern that his praise could be taken as criticism due to the sometimes imprecise way that the term “addiction” is used. Thus, the tester admirably clarified what he meant in the assessment:

[H]e feels the game last longer because he doesn’t play it obsessively.

Edutaining Kids Tester on Harvest Moon: A Wonderful Life

The tester appears to be alluding to what some today may describe as “burnout” – when a game with a large amount of content inspires frenzied devotion for a short time before the player spends so much time with it that he or she can no longer bear the thought of turning it on.

(In the area of laid-back gaming affairs, I think that there is an interesting point to analyze in this area by comparing the original Animal Crossing for Nintendo GameCube to the far more commercially successful Animal Crossing: New Beginning for Nintendo Switch, but I will set that aside for the time being.)

Thus, the tester believed that A Wonderful Life’s being “engrossing” but not “excessively addicting” extended its longevity. It inspired high engagement for limited periods rather than 12-hour benders for a week. This, by extension, perhaps contributed to its leaving a stronger and more favorable impression in the long run than an “excessively addictive” affair.

A Standard For Good Game Design?

Could “engrossing but not excessively addictive” be a meaningful guide-post for game designers who want to create works that withstand the test of time?

I only just came across the review (credit to Marginalia Search) and have thus not yet fully developed my thoughts in this area, but I do think that there is something to the idea.

For a game to be engrossing is for the game to have the sorts of qualities that inspire people to carefully attend to a game. To be engrossing without being excessively addictive suggests that the game inspires players to carefully attend to it in an active way and of their own intentional accord. That is, it is the quality of the game, and not gimmicks such as social media integration, penalties for taking time off, or micro-transactions that encourage people to carve out time for it. To spend meaningful time with a game makes it more likely that when the game is done (whether done for good or done until the player chooses to return to it in the future), the player will come away with a favorable impression of it and of the time he or she spent with it. Conversely, one who becomes habituated to playing an excessively addictive game is likely to eventually associate those long, mechanical stints at the computer or with a controller with a certain species of stress or malaise.

The classic Harvest Moon games are not examples of games that have universal appeal. They are inherently slow-paced while also being more challenging than modern Story of Season entries due to their having faster-moving day clocks and less user-friendly inventory management. Farming in a video game, not to mention the light in-game social and dating elements, is not for everyone. But I will note that on the occasions on which I talked to someone who, like me, played Harvest Moon: Back to Nature (PlayStation 1), Harvest Moon 64 (guess which console), or Harvest Moon: A Wonderful Life, that person not only had fond memories of the game, but also remembered specific details, namely which of the bachelorettes his or her character married. A quick internet search will reveal many such cases. To get that far in a Harvest Moon game requires some time investment (note A Wonderful Life is different in that marriage is central to the game’s progression and it has a distinct ending). That so many who spent time with it have clear and fond memories after the fact is a testament to the point that the early entries inspired meaningful engagement rather than addiction and inspired positive feelings in people who enjoyed that style of game and invested time in it.

(I would be surprised if FarmVille has a similar tendency.)

There is much discourse on dark patterns in games and other media (especially social media), that is, tacked on ancillary materials and factors to cause addiction separate from the game itself. Dark patterns are typically associated with games that are designed on a financial model that demands continuous engagement and financial transactions. Granting that designing games in this way is bad for players and for games as a medium, what is the alternative? A game that lacks dark patterns but also lacks redeeming qualities is not worth much in the end. We know what we want to avoid, but what do we aspire to?

Here, I suggest that “engrossing but not excessively addicting” is a good maxim to keep in mind. A game should have the aesthetic qualities to cause people to want to attend to it carefully, which is fundamentally at tension with a game that induces addiction artificially or otherwise causes people to develop a passive habit. Such a game will, like a good book or movie, leave people with a long-lasting favorable feeling. There are commercial benefits to that favorable feeling. I will venture that a majority of people who purchased Harvest Moon: A Wonderful Life when it came out were familiar with at least one of the series’ prior entries.

“Addictive” is a broad term with negative and positive connotations depending on the particular use-case. But in aspiring to make a great game, engrossing, rather than addictive, is a better-defined objective. A game about which one with well-ordered sensibilities can say is addictive in a positive way is most likely, if not necessarily, engrossing.