The original Game Boy Pokémon games were released as Pokémon Red and Green in Japan on February 27, 1996, and as Red and Blue in North America on September 28, 1998.

More than twenty years later, they remain not only among the best-selling video games of all time, but also the most influential, having launched a long-running series which continues today with the worldwide release of the ninth generation of main-line Pokémon games, Scarlet and Violet. As the Pokémon series explores new territory, I thought that it would be a good time to return to the originals. Specifically, with the aid of Mr. Julian Stefton-Green’s Initiation Rights: A Small Boy in a Poké-World, a short paper about his 6-year-old son’s interactions with Pokémon Red, Blue, and Yellow, published as part of Pikachu’s Global Adventure: The Rise and Fall of Pokémon (2004, Duke University Press).

A short introduction to the material

Pikachu’s Global Adventure: The Rise and Fall of Pokémon was a 2004 collection of writings about the early years of Pokémon in the United States from psychology, sociology, and education perspectives.

Full citation: Tobin, Joseph. (2004). Pikachu's Global Adventure: The Rise and Fall of Pokémon. Duke University Press.

Some reviews of the book have observed that its assessment that Pokémon’s popularity had abated turned out to be inaccurate – but that lack of foresight does not diminish the quality of a couple of the better pieces in the collection (to be fair, I will argue that while Pokémon remains a phenomenally successful franchise, 1998 and 1999 remain the apex of its popularity and influence in the United States).

The finest essay in the collection is Mr. Sefton-Green’s Initiation Rites: A Small Boy in a Poké-World. Mr. Sefton-Green, who was then the head of media arts and education at WAC Performing Arts and Media College and a published author on the subject of youth culture and multi-media, studied how Sam, his six-year old son, interacted with the original Pokémon games. (You can see what Mr. Sefton-Green is up to in 2022 on his personal website). Although Mr. Sefton-Green was a professional academic, he was not personally well-acquainted with playing video games. Nevertheless, his study of his Sam, his then six-and-one-half-year-old son, was written with careful attention to detail, and it leaves me as a reader with a strong impression. (I will note that his son, like me, received his copy of Pokémon for Christmas in 1999, although I will note that I was a bit older than Sam.)

In this article, we will focus on one particular passage toward the end of the paper wherein Mr. Sefton-Green discussed how despite going against contemporary trends in video games toward greater and greater graphical and technical prowess, Pokémon Red, Blue, and Yellow had captured his son’s imagination. The essay is especially timely as the Pokémon series, between its new releases in Scarlet and Violet and the spinoff Pokémon: Legends Arceus, which was released earlier in 2022, endeavor to take the series in a new direction and, I will argue somewhat counter-intuitively, return it to its roots.

Mr. Sefton-Green’s passage on Pokémon and imagination

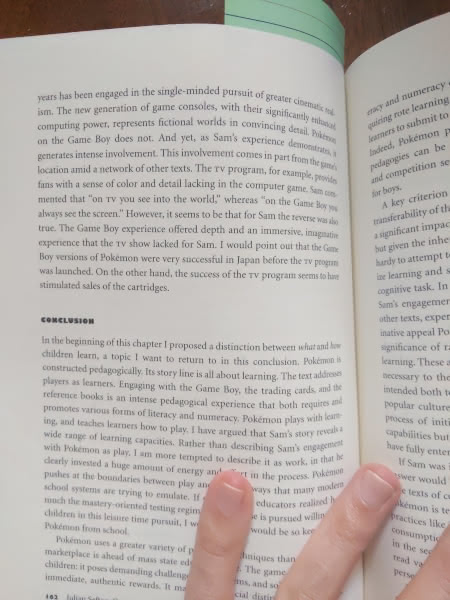

Mr. Sefton-Green’s passage comes close to the end of chapter seven of Pikachu’s Global Adventure. If you happen to have the volume, the passage begins toward the bottom of page 161 and runs into page 162. In considering the passage, bear in mind that Mr. Sefton-Green was describing the state of affairs in video games and Pokémon as they were in 1999. Let us first work through what he wrote before conducting our analysis of two points he made from a 2022 perspective.

Mr. Sefton-Green began the section:

…[T]he Pokémon game flew in the face of dominant patterns of game development in the computer-gaming industry, which for years has been engaged in the single-minded pursuit of greater cinematic realism.

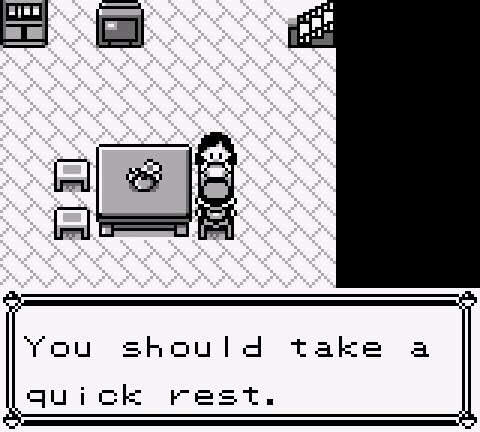

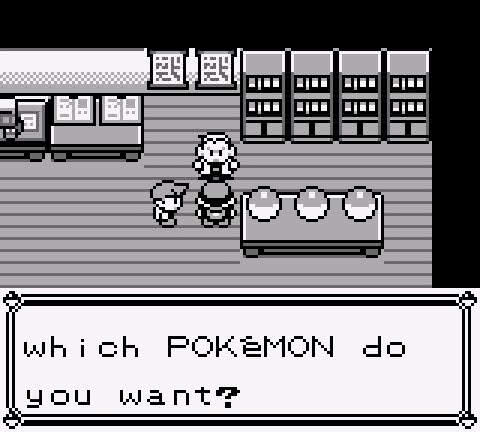

The visuals of the original Pokémon games, which were designed for the black and white Game Boy rather than the Game Boy Color, were simple even by the standards of 1996 (when Pokémon was released in Japan), much less by the standards of 1998 when they made their way to the United States.

While most of the best-looking games of 1998 and 1999 look primitive today, I agree with Mr. Sefton-Green that the trend in the video game industry was inclined toward offering more graphically impressive, or cinematic experiences. That trend began with the first successful 3D-first consoles (namely PlayStation and Nintendo 64) and accelerated with the release of the Sega Dreamcast.

I have previously written about how some video games which were not noted for being the most visually impressive in their day have aged better in terms of graphics than some games which were more highly regarded in that area. For example, I opined that one would be hard-pressed to find a more aesthetic game from the 1990s than Super Mario World 2: Yoshi’s Island, which was a 16-bit Super Nintendo game. However, Pokémon Red, Blue, and Yellow are not an examples of games which aged especially well visually (other than through nostalgia-tinted glasses). One could make the case that Pokémon Crystal for the Game Boy Color, the last of the six main-line Pokémon games released before the series moved to Game Boy Advance, was a genuinely impressive visual effort which does age well. By comparison, Pokémon Red, Blue, and Yellow are quite a bit simpler.

Pokémon Red and Blue looked primitive the moment when they were released in the United States. Much of its audience had more powerful consoles with immersive, 3D graphics. Yet Pokémon was the most popular game in the world. How do we explain this? Mr. Sefton-Green, who closely watched his son play Pokémon, took a stab at an answer:

The new generation of game consoles, with their significantly enhanced computing power, represents fictional worlds in convincing detail. And yet, as [my son] Sam’s experience demonstrates, Pokémon generates intense involvement.

More visually impressive affairs presented players with detailed worlds. Pokémon presented players with simple sprite art. Yet, despite its lack of visual flair, Pokémon “generate[d] intense involvement.” Having been on the kid side at the time, I agree entirely with Mr. Sefton-Green’s assessment. But how did it generate this involvement? I return to the author:

This involvement comes in part from the game’s location in a network of other texts. The TV program, for example, provides fans with a sense of color and detail lacking in the [Game Boy] game. Sam commented that ‘on TV you see into the world,’ whereas ‘on the Game Boy you always see the screen.’

Although Pokémon itself was visually simple, it was the center of a network of related media. The TV show, which still runs today, was very popular at the time, even with some children who did not play the Pokémon game. The show passed through most (but not all) of the locations in Pokémon Red, Blue, and Yellow, and also visited locales that did not exist in the game. Much of the discussion about the show in my class was how terrible the protagonist, Ash Ketchum, was at Pokémon battling (it seems he has improved more than he has aged in the ensuing two plus decades). But there is no question that seeing full-color depictions of Kantonian locales added color to the world on the Game Boy screen (note: the generation one Pokémon games take place in Kanto).

Before continuing, I will addend Mr. Stefton-Green’s analysis to note specifically that the Pokémon art-work, featured prominently in guides (see my articles on a Japanese Pokémon guide and an American Pokémon guide in adventure-book form) and on Pokémon cards were also very important in that they brought the Pokémon, the most important part of being a Pokémon trainer, to life. Mr. Ken Sugimori’s original watercolor Pokémon designs were quite striking, and I like to think that they improved the aesthetic sensibilities of the children who spent time with them. I will add additionally that Pokémon Stadium and Pokémon Snap released in the United States in 1999 for the Nintendo 64 were quite exciting in that they allowed players to see what Pokémon looked like in full 3D on what was then a powerful console.

Is that the end of the matter? Is it the case that the Pokémon games generated intense involvement in spite of their visual simplicity? Were they saved from what would have otherwise been a fatal flaw by the fact that there were more vivid depictions of Pokémon and Kanto in other media? Mr. Sefton-Green considered the matter and concluded that this may not have been the state of affairs:

[I]t seems to me that for Sam the reverse was also true. The Game Boy experience offered depth and an immersive, imaginative experience that the TV show lacked for Sam.

I highlighted the crucial part of Mr. Sefton-Green’s astute observation, and I will return to it momentarily after we finish is passage, wherein he offered concrete evidence to support his assessment:

I would point out that the Game Boy versions of Pokémon were very successful in Japan before the TV program was launched.

By “very successful,” we mean that Pokémon Red and Blue were the best selling games of all time in Japan, not to be surpassed for a quarter-century. They achieved that success initially without the sea of related media which accompanied Pokémon’s arrival in the United States. To be sure, that a game was successful in Japan is no guarantee that it will be similarly successful under the same conditions in the United States, especially in the mid-to-late 1990s. However, Pokémon’s unassisted initial success in Japan is strong evidence that although, as Mr. Sefton-Green would note in the next sentence, “the success of the TV program seems to have stimulated sales of the cartridges,” there was something special about the games in and of themselves which caused them to become defining achievements for Nintendo.

Imagination and a sense of wonder encircled the Pokémon world

The original Pokémon games were not successful because of cutting-edge graphics, for there were none. Moreover, they were not successful because they had a moving story or snappy dialogue like some other classic role playing games which age well largely on the basis of their excellent plots or clever choices. Rather, the original Pokémon’s story is simple: A 10-year old boy sets off on a journey to see every Pokémon in the world, become the Pokémon League Champion, and thwart the sinister plans of an evil organization on the way.

The most memorable dialogue in the original Pokémon games is about shorts.

Hi! I like shorts! They’re comfy and easy to wear!

Yet despite these supposed shortcomings, Pokémon Red and Blue were the most commercially successful and significant video games of the 1990s and remain fun to play more than two decades after they were released. How can this be? Mr. Sefton-Green said it well:

The Game Boy experience offered depth and an immersive, imaginative experience…

This almost covers everything.

While there are many rules (and glitches) which govern the quaint world of Pokémon generation 1 Kanto, many of which were mysterious to youngsters of the day (Mr. Sefton-Green also examined the demystification of Pokémon mechanics), Pokémon offered young players a sense of freedom.

The player takes the role of a 10-year old, which was close to the age of much of Pokémon’s audience, going off on a grand adventure (but with a loving Mother at home always there to heal his Pokémon).

The player would begin with only a single Pokémon companion, and grow with his or her companion while encountering new Pokémon and trainers throughout the journey.

With 151 Pokémon to ultimately choose from (depending on one’s access to Mew), children could create their own stories as they chose the Pokémon to accompany them on their quests to become the best trainer. While few kids fully understood the mechanics, it was the case that Pokémon of the same species were distinguishable in terms of stats, adding even greater variety to the adventure. Moreover, after winning the second of eight required Gym badges, the world opened up greatly, giving the player the freedom to explore and capture gym badges and achieve other in-game milestones in whichever order he or she chose.

The original Pokémon games are deep in terms of the number of Pokémon and moves offered and their mechanics. They are immersive in that they offer the player freedom to tackle the game in countless ways (not to mention with all of the original Pokémon games’ unintended glitches, there was much to discover beyond what had been intentionally implemented by the developers). However, depth and immersion are qualities of many good games. That is, it may be true that Pokémon was both deep and immersive, but that hardly explains why Pokémon Red and Blue are collectively one of the most significant games of all time. Mr. Sefton-Green’s final point, imagination, is the most significant. But before we cover that, I quote from Nintendo Life’s qualified favorable review of the newest Pokémon games, Scarlet and Violet (note: I am writing this article on the eve of the release of Scarlet and Violet, so it goes without saying that I have not yet started my pre-ordered copy of Violet). One passage from the review, written by Ms. Alana Hagues, caught my attention:

[I]f anything has come close to recapturing the real magic we felt when we discovered our first Pokémon world in Red & Blue, it’s Pokémon Scarlet & Violet’s vast and open Paldea region.

This passage captured my attention because I had already been thinking about recapturing that something from Pokémon Red and Blue while playing Pokémon Legends: Arceus, which is a spinoff game (I would argue it is a bit of a proof of concept) that was released in February 2022.

However, before I address the current state of Pokémon, what was the “magic” of the original Pokémon games?

In order to have magic, it was necessary, but not sufficient, that the games have depth and the capacity to immerse the player through game-play. What made Pokémon Red and Blue special was how they inspired the imagination. That Pokémon lacked visual flair and a strong script aided rather than hindered its most important quality. Because the world of Pokémon Red and Blue was composed in simple sprites (and without any color for children still on Game Boy Pocket) children were inspired to see the world in full color. One can imagine a young kid who had started the game with Charmander remembering how he overcame a type disadvantage in his first two Gym Battles, a kid remembering how he stumbled into the Power Plant or Seafoam Islands only to end up in battle with a legendary bird, or that time a young player finds himself hopelessly lost in the Safari Zone (maybe that last one is just me). This is a different sort of game memory than the type associated with clearing a challenging level. My 2022 review of a 1999 Pokémon strategy guide in novel form was ultimately unfavorable as both a work of literature and a practical strategy guide, the concept was ingenious because it matched (perhaps inadvertently) how children interacted with Pokémon Red and Blue. I dont understand the final sentence :(.

While the Pokémon artwork, TV show, and other media gave children a framework for imagining the simple world on their screens as something grander, children themselves created the images of their own adventures based on the framework provided by the Game Boy game.

Despite their simplicity in terms of visuals and writing, the original Pokémon games inspired aesthetic wonder. They did so in a unique way. I still remember the first time I saw Super Mario 64 and was struck by its bold 3D environment (note my only consoles at the time were the Sega Genesis and Game Boy) or the first time I saw Sonic outrunning an orca in Sonic Adventure for the Dreamcast. Those inspired a type of wonder, but a wonder of a lesser species than Pokémon Red and Blue. The wonder of Pokémon Red and Blue was setting off on a grand adventure to not only become the best in the world, but also to catalog the creatures of the world. You set off with nothing but a single Pokémon, a vague direction, and a few goals. Pokémon Red and Blue were and are mechanically excellent games, but technical excellence does not complete the circuit. What was significant was that every adventure in Pokémon Red and Blue was unique, and every adventure was truly the player’s own adventure.

For children whose worlds appeared limited because their worlds were small, Pokémon Red and Blue “satisf[ied] that longing which exists in every human breast to be able to say: This is mine.” (Quoting Calvin Coolidge, see my article on the quote.)

The future of Pokémon

Pokémon Legends: Arceus, is, in many respects, more distant from the original Pokémon Red and Blue than the main-line Pokémon games (Arceus fell between the eighth and ninth generations of the main series). It was, prior to today’s release of Scarlet and Violet, the most visually ambitious Pokémon game by a wide margin. It comes with a setting and mechanics unlike any seen in the main series. Whereas the main series Pokémon games all follow the formula established by Red and Blue of collecting badges, filling up a Pokédex, and defeating an evil organization (note: generation seven’s Sun and Moon had some refreshing twists on the formula, but it ultimately ended in the same place as the others), Legends Arceus transports a modern boy or girl into an ancient version of Sinnoh (the setting of the generation four Pokémon games, Diamond and Pearl) where there are few people and many untamed Pokémon. The modern concept of a “Pokémon trainer” does not exist, and there are certainly no “Gyms” or “Elite Fours.” Instead, the player is tasked with documenting Pokémon in the wild about whom little is known by the inhabitant’s of the game’s world. The player is given great freedom to explore vast environments and is encouraged to catch and defeat many Pokémon to fulfill different research objectives. All the while, the player may advance the plot, which involves lore from the world, generally at his or her leisure.

Despite the fact that Legends: Arceus diverges from the standard formula established by Red and Blue and refined (in some cases, notably generations six (X/Y) and eight (Sword/Shield), over-refined) in later entries, I found that it came the closest to recapturing the sense of wonder from Pokémon Red and Blue since any entry since generation three’s Ruby and Sapphire. (Generation two’s Gold and Silver is the finest Pokémon generation and, for reasons I discussed, very much captured the magic of the originals and did so in a unique way.)

(To be clear before continuing, I like all of the Pokémon generations in a vacuum – even generation six’s X/Y, which I had the most problems with. I must confess I still have yet to play Black/White and Black 2/White 2 of generation five, but I plan to rectify that shameful oversight in the near future.)

Video games, and the world that children grow up in, is very different now than it was in 1996 (when Pokémon was first released in Japan) and 1998 (when Pokémon was first released in the United States). Pokémon Red and Blue allowed children whose worlds were small to set off on their own adventure. Today, children seem to use internet-connected phones before they can talk. Multi-player in 1998 meant physically connecting Game Boy consoles. Multi-player in 2022 may mean engaging in a random Pokémon trade with someone who lives on the other side of the world.

Pokémon Red and Blue remain great games because their good qualities are timeless. People my age still fondly remember them, and they are still fun to play today. Will children whose first Pokémon game was Sword and Shield (generation 8, released in 2019) remember those games in the same way? Despite the fact that Sword and Shield follow roughly the same formula, albeit with pacing issues, a confusing story, and less allowance for player autonomy, I think not. (However, let it be said that I like Sword and Shield, and the games did much to make competitive multiplayer battling more accessible, albeit they are on the lower side of my Pokémon ranking.)

Recapturing the magic of Pokémon Red and Blue does not mean recreating the same formula with a new coat of paint, gimmicks, and less player freedom. It requires considering the video game environment and culture as it exists today and, taking full advantage of modern hardware (we will set aside the Switch’s deficiencies in terms of high-end power), and offering an experience which captures the aesthetic qualities of the original Pokémon Red and Blue and its immediate successors.

Pokémon Legends: Arceus, was a very encouraging sign that the team behind Pokémon is thinking about the path forward in the correct way. Gone was the heavy-handed story, over-reliance on gimmicks, excessive hand-holding, and restrictions on player autonomy. Where recent Pokémon games restrict the player’s freedom of movement and action to a far greater degree than the original Pokémon games for Game Boy, Legends: Arceus, invited the player to a new land and new kind of adventure with familiar creatures in an unfamiliar world. More than any Pokémon game since Gold and Silver, Legends: Arceus inspires the player to look around and discover the world around him or her. Legends: Arceus is as much of a departure from the main-line series as the two Pokémon Colosseum spinoffs for the Nintendo GameCube from the early 2000s, but more than any main-line Pokémon entry in a long while;it captures the spirit and approximates the magic that made Pokémon a defining video game series in the first place.

Pokémon Legends: Arceus, is by no means a perfect game – and it does not have the same significance in its time that the early Pokémon adventures had in theirs. However, it does represent something positive for the Pokémon series – it is an indication that the Pokémon team is working to create games around the core ideas and sensibilities which inspired the Pokémon series. The best quote to highlight what represents comes from the generation two Pokémon games, Gold and Silver, which, as I noted and discussed in a 2020 article to mark the twentieth anniversary of their U.S. release, were the finest main-line Pokémon entries. I present the town slogan for New Bark Town, the starting location for the greatest Pokémon adventure to date:

The Town Where the Winds of a New Beginning Blow.

(New Bark Town also inspired The New Leaf Journal’s slogan.)

Legends: Arceus, I hope, represents a new beginning for the series. It was perhaps fitting that it was set in the beginning. While it appears from early first-hand impressions that the newly released Scarlet and Violet may have their share of growing pains, it also appears that they are incorporating some of the open world ideas introduced in Legends: Arceus into the main-line series. I look forward to starting Pokémon Violet, and I hope that it brings the series a step closer to providing the sort of “immersive, imaginative experience” that Pokémon Red and Blue game Mr. Sefton-Green’s son and countless other players, young and old, 24 years ago.