The tradition of life masks dates back to antiquity. In the nineteenth century, John Henri Isaac Browere, an American artist, created life masks of many leading Americans from the revolutionary era and early republic. photographs of his works were compiled into a single volume in an 1899 book titled Browere’s Life Masks of Great Americans by Charles Henry Hart, available on Project Gutenberg. Before devoting chapters to many of Browere’s individual life masks of great Americans, the book provided an introduction to Browere’s life and work, placing it in the context of when he lived.

(Note: All images in this article are clipped from the Project Gutenberg edition of Hart’s book.)

Below, I will follow Charles Henry Hart’s text in providing an overview of Browere the artist. I published a follow-up article examining Browere’s death mask of the fifth President of the United States, James Monroe – the only death mask that Browere is known to have made.

Chapter on John Henri Isaac Browere

In writing the following overview, I am relying primarily on the chapter on Browere and his life from Browere’s Mask of Great Americans. You can follow along with the original text here.

Early Life and Family

John Henri Isaac Browere was born at No. 55 Warren Street in New York City (Manhattan) on November 18, 1792. He was the son of Jacon Browere and Ann Catherine Gendon.

Browere was of Dutch descent. The first of his family to settle in the Americas was Adam Berkhoven, who moved to Long Island in 1642. Berkhoven started a business that was named either Brouwer or Brewer, and the business name became attached to him. That name was transmitted to Berkhoven’s descendants, which thus explains why the artist that we study here was John Henri Isaac Browere.

Becoming an Artist

Browere entered Columbia College as a student, but he never graduated. Hart believed that Browere’s not graduating college was related to his April 30, 1811 marriage to Eliza Derrick, who was from London.

Instead of persisting in his formal education, Browere studied art under Archibald Robertson, a miniature painter who moved to the United States from Scotland in 1791 pursuant to a commission from David Stuart, then Earl of Buchan, to paint a portrait of George Washington. Browere attended Robertson’s Columbian Academy, which Robertson maintained as an art school for men and women for three decades.

Browere did not study only in the United States, but also abroad. Browere’s brother was the captain of a trading-vessel, and he invited John to accompany him to Europe. John Browere spent two years traveling Europe by foot and studying art, with a specific interest in sculpture. Upon his return, Browere crafted a bust of Alexander Hamilton based on a Robertson miniature painting. The bust was well-received, Hart stated that it “was pronounced a meritorious attempt to produce a model in the round from a flat surface.”

Browere Begins Making Life Masks

Browere’s interest in life masks appears to have followed his interest in sculpting: “Being of an inventive turn, he began experimenting to obtain casts from the living face in a manner and with a composition different from those commonly employed by sculptors.” Through trial and error, Browere refined his process for creating life masks.

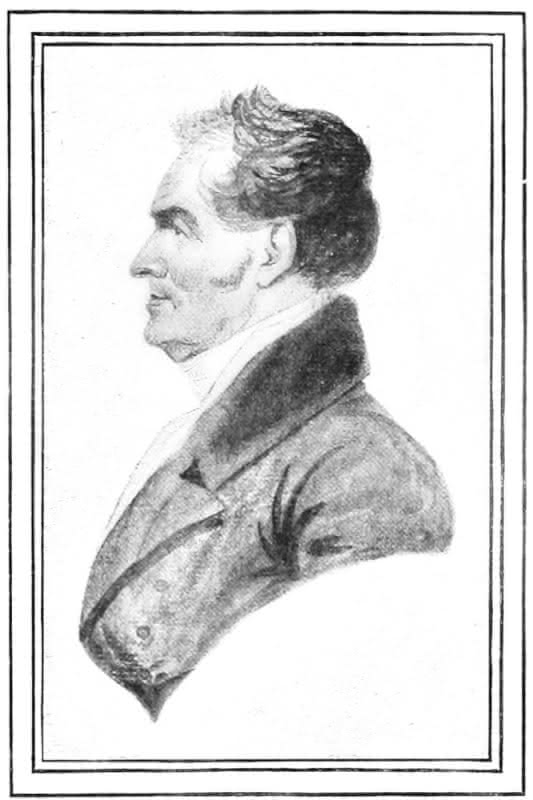

Browere’s first successful mask was that of his teacher and mentor, Archibald Robertson. However, Hart described Browere’s 1817 life mask of John Paulding, one of the three men who captured Major John Andre during the Revolutionary War, as the most important of his early works.

Browere would later create life masks of David Williams and Isaac Van Wart, who had worked with Paulding to capture André.

Browere began to gain notoriety as an artist for his paintings, sculpting, life masks, and poetry. His work was exhibited at the American Academy of the Fine Arts on Chambers Street in Manhattan. Browere’s old teacher, Archibald Robertson, was one of the directors of the Academy – and he submitted the following card with the exhibition:

Having for many years been intimately acquainted with John H. I. Browere, of the City of New York, I deem it a duty which I owe to him as an artist, and to the public as judges, to say that from my own observation of his works both as a painter, poet, and sculptor, I think him endowed with a great genius by nature and first talents by industry. This my opinion, his works lately exhibited in the Gallery of the American Academy of Fine Arts, New York, fully justify and is amply corroborated by all, who with unprejudiced eye, view the works of his hand.

Archibald Robertson

While Browere was a man of many artistic talents, a certain event in 1825 would cause him to devote the main of his attention to life masks.

Browere’s Rise and Struggle in Sculpting and Life Masks

New York officials asked the Marquis de Lafayette to allow Browere to make a life mask of his face. Lafayette agreed, and Browere completed Lafayette’s life mask in July of 1825.

Browere’s life mask of Lafayette was well-received, and its success caused him to become “devoted to making casts of the most noted characters in the country’s history, who were then living, with the purpose of forming a national gallery of busts of famous Americans.” Hart explained that Browere intended to have his life masks reproduced in bronze. In a letter to James Madison, whom he had created a life mask of, Browere wrote:

Pecuniary emolument never has been my aim. The honor of being favored by my country biases sordid views.

Browere to James Madison

1821 bust of John Paulding

Browere accumulated great funds in furtherance of his project. In an 1828 letter to James Madison, Browere wrote that he had spent $12,087 (about $350,000 in 2022) in creating the masks he had already completed. As of his letter to Madison, he had already created masks of Madison, John Adams, John Quincy Adams, and Thomas Jefferson.

Struggles, Criticisms, and Controversies

Hart noted that Browere’s ambitions ran into practical difficulties. Foremost among the difficulties was that “[t]he time … was not ripe for the public patronage of the Fine Arts.” Another issue that Browere faced was the lack of protection for sculptures. Browere wrote the following to Madison:

I regret to say that as yet no law has been passed to protect modelling and sculpture, and therefore I have been hindered from completing the gallery, fearful of having the collection pirated.

Browere to James Madison

Browere became discouraged by the lack of interest in his project. Hart contemplated relocating to Panama where he would create busts of prominent figures in South America in order to encourage them to pursue their freedom, but this plan never materialized. Browere would eventually abandon his plan to create a national gallery due to a lack of financial support and opposition from luminaries in the art world.

Hart concurred with Browere’s assessment that his project was stymied by opposition from leading artists and patrons of the day. According to Hart, Browere was maligned for accurately describing his method for taking life portraits as “a process.” His work was criticized for lacking artistic merit. Moreover, Browere was attacked in newspapers for allegations of mistreatment when he took a life mask of the elderly Thomas Jefferson.

I conducted my own research using the Elephind newspaper search engine and found contemporary accounts of the allegations. The Richmond Enquirer alleged that Jefferson had nearly suffocated during the process of Browere’s taking his life mask after Browere allowed the plaster to become too hot (see article). Browere wrote his own account of the affair in 1825 (see letter). According to Browere, he received a letter of introduction from James Madison, who was satisfied with his own life mask, to give to Jefferson. Browere stated that he originally intended to only take a mask of Jefferson in lieu of a full bust, in recognition of Jefferson’s advanced age, but decided to take the full bust. Browere stated that four ladies came into the room as he was removing the plaster cast from Jefferson and “troubled me with their exclamations and surmises, and thereby retarded my progress considerably.” Browere noted that Jefferson was slightly light-headed when he stood, but was fine and that the effort had been successful.

Hart noted that the dispute over Browere’s treatment of Jefferson was resolved by Jefferson himself. Thomas Jefferson wrote in response to the attacks on Browere:

Mr. Browere never has followed and will never follow the usual course, knowing it to be fallacious and absolutely bad. The manner in which he executes his portrait-busts from life is unknown to all but himself, and the invention is his own, for which he claims exclusive rights, but it is infinitely milder than the usual course.

Thomas Jefferson

Hart noted that others subjects praised Browere for taking busts without causing the usual discomfort associated with the process. Letters of support came from Jefferson, John Adams, James Madison, Lafayette, Gilbert Stuart, and others.

Hart noted that neither Browere nor his son, who worked with him, wrote anything about Browere’s process for taking life masks – thus leaving it as one of the “lost arts” as of 1889.

Browere’s relationship with leading art figures and patrons of the day continued to deteriorate. Hart reprinted several communications that you will find in the text of his book, but they are too granular for the instant survey.

Browere’s Death and the Loss and Rediscovery of His Work

Browere passed away on September 10, 1834, at his home in Manhattan, after a short bout with cholera. He was buried in the Carmine Street Churchyard.

Browere’s decisions on his death bed would cause his work to disappear from thought and mind for many decades. Hart described Browere’s final orders with a touch of editorializing:

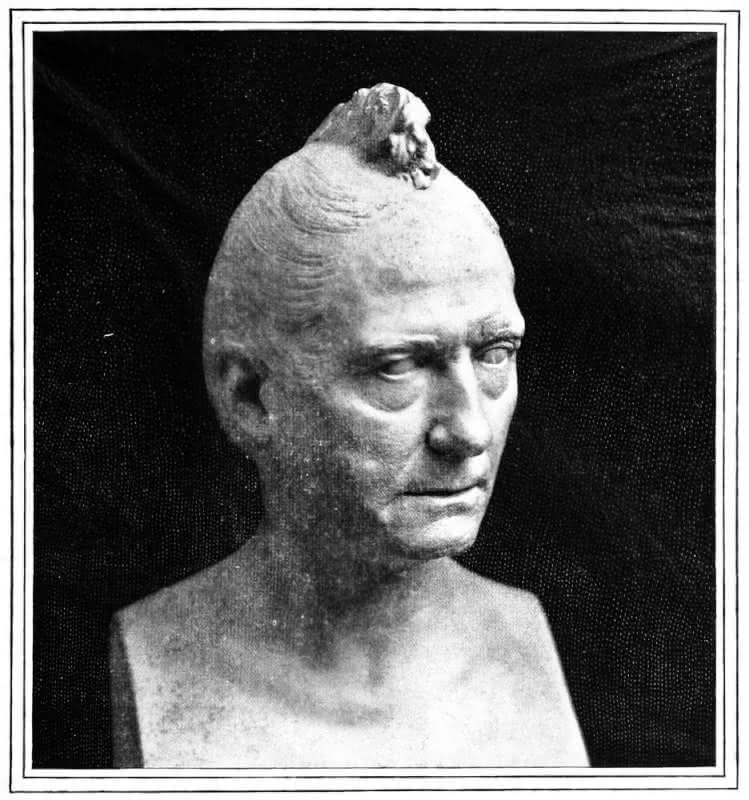

[I]t is pathetic to picture the disappointed sculptor, on his deathbed, directing, as he did, that the heads should be sawed off the most important busts, and boxed up for forty years, at the end of which period he hoped their exhibition would elicit recognition for their merit and value as historical portraits from life.

Hart stated that Browere’s final request for the mutilation of his sculptures was not carried out. However, his life masks were indeed boxed up, and “the busts never saw the light of day until the Centennial year [of 1876], when a few of them were placed on exhibition in Philadelphia.” Hart noted that because the sculptures were not directly connected with the national centennial celebration, they “were not in a position to attract attention.” So anonymous was their presence at the centennial that “the fact of their exhibition … [had] only recently become known.”

Browere left behind his wife and eight children. His second child, Alburtis D.O. Browere, achieved some success as a painter after his father’s death. Hart noted that Alburtis D.O. Browere was known for several paintings featuring Rip Van Winkle and some of his work painting mining scenes during the California gold rush. While Hard criticized Alburtis for the decision to add draperies to his father’s busts of great Americans, he credited Alburtis with “his filial reverence that preserved invaluable human documents, and has permitted us to see and know how many of the great characters who have gone before really appeared in the flesh, how they actually looked when they lived and moved and had their being.”

Hart’s Assessment of Browere

Having followed Hart’s account of Browere, I will conclude with the author’s assessment of the artist’s body of work:

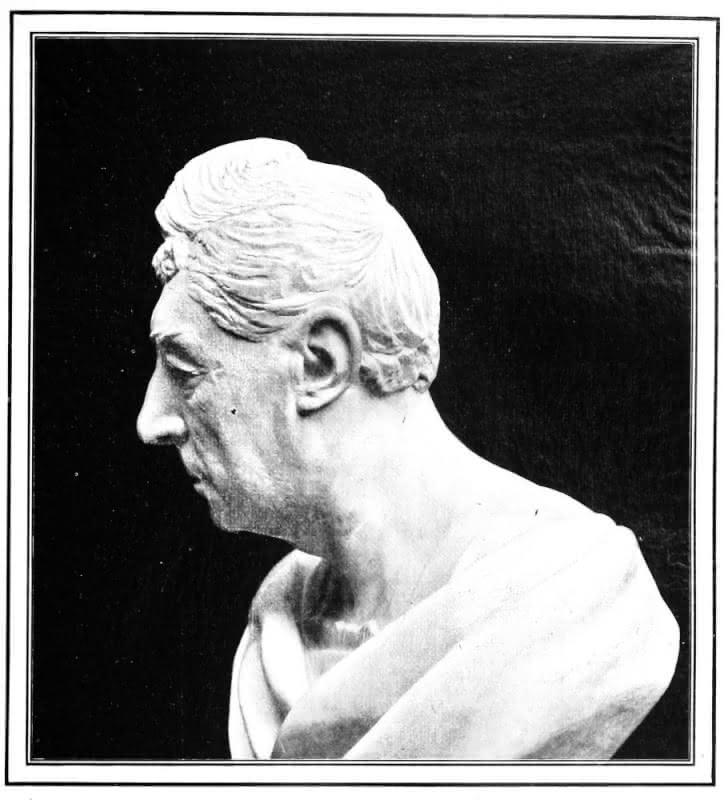

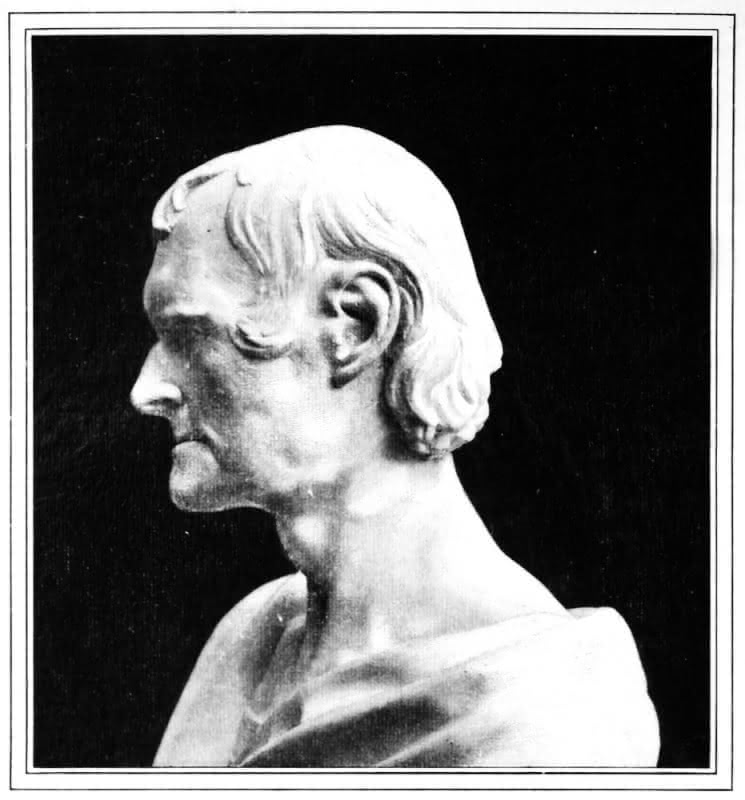

Call Browere’s work what one will,—process, art, or mechanical,—the result gives the most faithful portrait possible, down to the minutest detail, the very living features of the breathing man, a likeness of the greatest historical significance and importance. A single glance will show the marked difference between Browere’s work and the ordinary life cast by the sculptor or modeller, no matter how skillful he may be. Browere’s work is real, human, lifelike, inspiring in its truthfulness, while other life masks, even the celebrated ones by Clark Mills, who made so many, are dead and heavy, almost repulsive in their lifelessness. It seems next to marvelous how he was able to preserve so wonderfully the naturalness of expression. His busts are imbued with animation; the individual character is there, so simple and direct that, next to the living man, he has preserved for us the best that we can have—a perfect facsimile. One experiences a satisfaction in contemplating these busts similar to that afforded by the reflected image of the daguerreotype. Both may be “inartistic” in the sense that the artist’s conception is wanting; but for historical human documents they outweigh all the portraits ever limned or modelled.

Browere’s busts of great figures, based on his life masks, are indeed striking and life-like. Debates about the place of taking life masks in art aside, his portraits provide a valuable glimpse into the faces of many of the prominent men and women of the early American Republic.