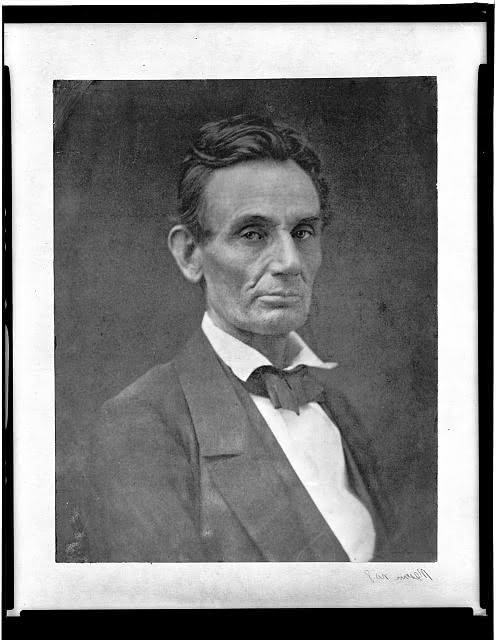

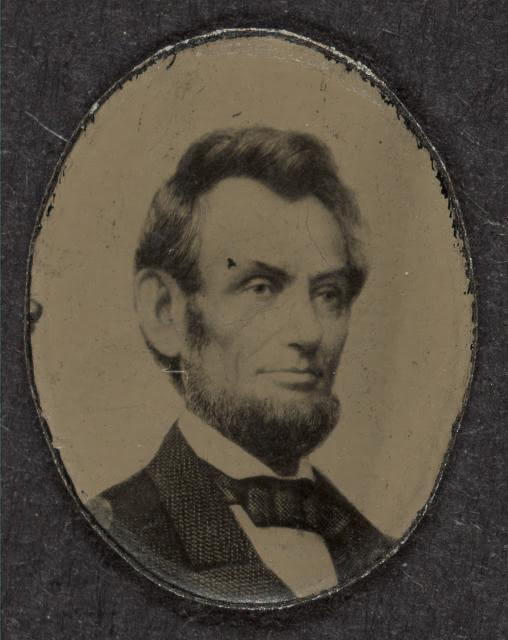

As December 1864 prepared to turn into January 1865, the Union Army was making decisive progress toward its ultimate victory over the Confederate States of America in the American Civil War, which had begun in 1861. Then-President Abraham Lincoln had won reelection by a wide margin in November 1864. December brought two dramatic victories for the Union forces. Firstly, General G.H. Thomas led his troops to a significant victory in Nashville which sidelined the Confederate Army of Tennessee for what was left of the war (see our article). On December 26, Lincoln sent a telegram to general William Tecumseh Sherman. thanking him for his “Christmas gift” of the capture of Savannah, Georgia. While managing the War effort from the White House, Lincoln sometimes intervened in matters involving soldier discipline. In this article, I will examine a particularly complicated case wherein, on December 29, 1864, Lincoln intervened in the matter of Frank R. Judd, a soldier who was to be tried, and likely executed, for desertion. The matter was complicated, as we will see, because Frank R. Judd was the son of the Norman B. Judd, the United States Minister to Prussia and Lincoln’s long-time friend and confidant

Lincoln’s Telegram to General Butler (December 29, 1864)

On December 29, 1864, Abraham Lincoln sent the following telegram to Major General Benjamin Butler:

There is a man in Company I, Eleventh Connecticut Volunteers, First Brigade, Third Division, Twenty-fourth Army Corps, at Chapin’s Farm, Va.; under the assumed name of William Stanley, but whose real name is Frank R. Judd, and who is under arrest, and probably about to be tried for desertion. He is the son of our present minister to Prussia, who is a close personal friend of Senator Trumbull and myself. We are not willing for the boy to be shot, but we think it as well that his trial go regularly on, suspending execution until further order from me and reporting to me.

It had come to Lincoln’s attention that a soldier who went by the name William Stanley, but whose actual name was Frank R. Judd, had been arrested for desertion at Chapin’s Farm, Virginia, and that he would likely be convicted and executed. Lincoln made his personal interest in the matter of Frank R. Judd clear. Frank R. Judd was the son of the U.S. Minister to Prussia, Norman B. Judd. Norman Judd not only served in Lincoln’s administration but was also “a close personal friend” of Lincoln and Lyman Trumbull, who was then a United States Senator from Illinois.

As we will discover, Lincoln would ultimately spare the life of Frank Judd – who was fortunate that Lincoln held his father and his father’s friends in high esteem. Upon researching, I learned that Lincoln himself had, at the request of Norman Judd, previously ensured Frank Judd’s appointment to West Point. Below, I will take a summary look at the relationship between the four men noted in Lincoln’s telegram and how events led to Lincoln intervening in a military case to prevent Frank Judd’s execution.

Lincoln, Judd, and Trumbull in Illinois

Note that my purpose in this section is not to provide a comprehensive discussion of the very interesting Illinois political situation of the 1840s and 1850s, in which Lincoln, Judd, and Trumbull played leading roles. I seek only to provide a general overview to establish that Lincoln and Judd had a close, sometimes complicated relationship in the political sphere, and that their shared political battles had led to them becoming close friends. This context is necessary for understanding the events involving Frank Judd in 1863 and 64. For a more comprehensive look at the relationship between Norman Judd and Lincoln and their roles in Illinois and national politics in the 1850s, I recommend this well-sourced survey from Mr. Lincoln & Friends, which I relied upon in part to inform this section of the article.

Lincoln, Norman B. Judd, and Lyman Trumbull were three of the most important political figures in Illinois in the middle years of the nineteenth century. We will pick up events in earnest in 1854 and 55.

Lincoln had served for eight years in the Illinois House of Representatives (1834-42) and had represented Illinois for one term in the United States House of Representatives (1847-49). Lincoln had served in these elected offices as a member of the Whig Party, but by 1854 – where our story will principally begin – he had joined the newly formed Republican Party.

(See my article on Benjamin Harrison’s speeches accepting the Republican nomination for president in 1888 wherein Harrison addressed in brief the Whig-origins of the Republican Party.)

Both Judd and Trumbull were prominent Illinois Democrats who were known for opposing the ultimately ill-fated Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. Prior to 1854, Trumbull had served for a single term in the Illinois House of Representatives (1841-43) and then as a justice of the Supreme Court of Illinois from 1848-53. Norman B. Judd, who served in the Illinois State Senate from 1844-60, was a close ally of Trumbull.

In 1854, Illinois was choosing a Senator to replace outgoing Senator James Shields. Both Lincoln and Judd expressed interest in the position. U.S. Senators were then chosen by the state Senate, and Judd voted for Trumbull over Lincoln. Although Judd stood by this decision, it would come to cause him grief when he became a prominent figure in the Illinois’ Republican Party, which would consist both of former Whigs like Lincoln and, after 1856, former Democrats who had opposed the Kansas-Nebraska Act, including Trumbull and Judd.

By all accounts, Lincoln was not among those who begrudged Judd for not supporting him over Trumbull for Senate – recognizing that Judd at the time was a fellow Democrat and a close personal ally of Trumbull.

In answer to your first question as to whether Mr. Judd was guilty of any unfairness to me at the time of Senator Trumbull’s election, I answer unhesitatingly in the negative. Mr. Judd owed no political allegiance to any party whose candidate I was. He was in the Senate, holding over, having been elected by a democratic constituency. He never was in any caucus of the friends who sought to make me U.S. Senator—never gave me any promises or pledges to support me—and subsequent events have greatly tended to prove the wisdom, politically, of Mr. Judd’s course. The election of Judge Trumbull strongly tended to sustain and preserve the position of that portion of the Democrats who condemned the repeal of the Missouri compromise, and left them in a position of joining with us in forming the Republican party, as was done at the Bloomington convention in 1856.

Abraham Lincoln – Dec. 14, 1859 letter in defense of Norman B. Judd

By Judd’s reckoning, it was precisely because he had supported Trumbull that he had credibility at the time as an anti-Nebraska Democrat rather than a supporter of the Whigs/Republicans. When Lincoln subsequently engaged in his famous and ultimately unsuccessful battle with Stephen A. Douglass for Illinois other Senate seat, none other than Norman B. Judd, the former Democrat, was chairman of the central committee of the Illinois Republican Party. Judd played a leading role in Lincoln’s campaign – see for example this September 1858 letter wherein Judd offered advice to Lincoln for his next debate against Douglass and asked Lincoln for a list of upcoming appointments so that he could publish them in conjunction with then-Senator Trumbull’s appointments.

By all accounts, Lincoln believed that Judd had served him well in the campaign against Douglass.

My relations with Mr. Judd, since the organization of the Republican party, in our State, in 1856, and, especially since the adjournment of the Legislature in Feb. 1857, have been so very intimate, that I deem it an impossibility that he could have been dealing treacherously with me. He has also, at all times, appeared equally true and faithful to the party. In his position, as Chairman of the Committee, I believe he did all that any man could have done. The best of us are liable to commit errors, which become apparent, by subsequent development; but I do not now know of a single error, even, committed by Mr. Judd, since he and I have acted together politically.

Abraham Lincoln – Dec. 14, 1859 letter in defense of Norman B. Judd

The two became not only political allies, but also friends who engaged in business ventures. However, many of Lincoln’s allies accused Judd of having been incompetent or, worse yet, of having actively sabotaged Lincoln’s senate campaign for his own ends. This led to tension in their relationship. On December 1, Judd sent a letter to Lincoln complaining about personal attacks against him by Lincoln’s allies (Judd had sued one such individual, John Wentworth, for libel) and imploring Lincoln to defend Judd publicly. Lincoln responded on December 9, stating that while he did not like Judd’s tone, he disagreed strongly with all of the attacks against Judd. Judd was satisfied enough with Lincoln’s clarifications to make clear in his next letter on December 11 that he had not intended to blame Lincoln, that he would produce letters to help Lincoln defend him, and that he was prepared to assist Lincoln in his upcoming efforts to secure the Republican nomination for president in 1860.

By December 1859, both Lincoln and Judd were seeking higher office. Lincoln was considered one of the two leading candidates for the Republican nomination for president along with his future Secretary of State, and then-United States Senator William H. Seward of New York. Judd sought the Republican nomination for Governor of Illinois. While Lincoln declined to make an endorsement in Judd’s ultimately unsuccessful effort to secure the gubernatorial nomination, both on account of the fact that he was friends with both of Judd’s opponents and also his desire to stay out of factional party fights, he wrote a detailed defense of Judd and his character as a person and politician, dated December 14, 1859, addressing all of the charges against Judd in detail and allowing it to be published at the discretion of the recipients. (Compare the final draft with the first and second drafts.)

I dislike to appear before the public, in this matter; but you are at liberty to make such use of this letter as you may think justice requires.

Abraham Lincoln to Norman B. Judd in letter dated Dec. 14, 1859

Lincoln expressed to Judd that he hoped the letter would ameliorate the latter’s concerns and allowed for it to be published.

While Judd did not win the nomination for governor, we know well that Lincoln would win the Republican nomination for president before winning the general election in November 1860, prevailing over Seward on the third ballot. Judd played a significant role in the effort. It was apparently Judd’s idea and efforts – both of which Lincoln acknowledged – which led to that year’s Republican Convention taking place in Illinois. Judd took measures to ensure that Seward’s supporters in the Illinois delegation were seated toward the back of their block, and he formally nominated Lincoln for president on behalf of the delegation. Judd had hoped that Lincoln would choose him for a cabinet position, but those hopes were ultimately dashed – notwithstanding some indications that Lincoln had originally intended to include Judd in his cabinet. However, Judd remained in Lincoln’s circle, accompanying him for the better part of his dangerous journey from Illinois to Washington D.C. to assume the presidency on March 4, 1861, and making security arrangements for Lincoln on the trip.

Although Judd did not secure a cabinet position, Lincoln selected Judd as Envoy to Prussia, in which capacity he served from his confirmation on July 1, 1861, all the way through Lincoln’s assassination (Judd continued in his position for several months under President Andrew Johnson).

Lincoln agrees to help Frank R. Judd

Shortly after Lincoln assumed the presidency, the Civil War began in earnest. Judd was largely removed from events while serving abroad, but he made several trips back to Washington for events. While he was serving in Germany, Judd was concerned about the future of the eldest of his two surviving children, Frank R. Judd, who had been born in 1846.

On August 27, 1863, Norman Judd wrote a lengthy letter to then-President Lincoln from Europe requesting a personal favor:

Overwhelmed about as you must be with the pressure of public affairs, it seems like sacrilege to ask you to listen to private troubles and still I will venture— I want to put my son in the Navy (Frank R. Judd) — if, to reach a Midshipman’s warrant it is necessary to go through the Naval School, then I want him appointed to that School—

Norman B. Judd to President Abraham Lincoln — August 27, 1863

Judd explained to Lincoln that he was greatly concerned with his son’s conduct in Berlin:

There were several wild American young men here last winter — from five to Seven years older than F. and he unbeknown to me entered upon a course of dissipation more with women than wine— As soon as I discovered it — I sent him into the country to School, but the seeds of ruin are planted and unless arrested by discipline and occupation he is a lost boy— He desires to return to America and enter the Navy— A number of his former School fellows are in it, and they are constantly writing him— I can give him no occupation in Europe, and I dare not send him to the U. S. unless for a purpose as there is no one to control him— If I can place him under control until he is old enough to have judgment and self restraint it will save him— It pains me to write so of a favorite boy, but it was a necessity to show you that there was a higher motive than pensioning a boy upon the public— F. has the ability to do honor to any place — reads and speaks French, and German, and is one of the best gymnasts in his whole circle.

Norman B. Judd to President Abraham Lincoln — August 27, 1863

While Norman Judd’s concern with Frank in Berlin had to do with his base behavior, he still believed that if his son had potential to grow into an upstanding man if he was provided with the discipline that the military could provide. However, after detailing some more of Frank’s positive qualities, namely his physical fitness, Norman B. Judd concluded his request by noting how important he believed Lincoln’s decision was:

[C]an you help me save him I believe you will if you can and I think [Secretary of the Navy Gideon] Wells can find a place for him— I do not know how long I can restrain him in the country where he is and his present quiet is from the belief that I will ask this personal favor of you, and that it will be granted immediately.

Norman B. Judd to President Abraham Lincoln — August 27, 1863

On October 17, 1863, Norman Judd wrote a letter to then-President Lincoln while preparing to make a one-month return to the United States. The beginning of the letter reference to his prior request:

I do not know enough of naval arrangements to understand whether the position you name offers preferment to the capable and industrious or not— I explained to you my situation, and I believe this will be the turning point in Franks life, and so important do we regard it that Mrs J. urges me to go with F. to America and my inclination is to do so…

Norman B. Judd to President Abraham Lincoln — October 17, 1863

Both Norman Judd and his wife, Adelaide, believed that it was in Frank’s best interest to join the military. Here, Judd states that it was so important to his wife that his purpose in briefly returning to the United States was to make the request of Lincoln in person. Judd continued with a joke that would prove to be more than a bit eerie in hindsight:

To avoid leave of absence would keep me here a month and I am disposed to venture upon your generosity and secure my leave after I reach Washington— The interest here will in no way suffer by my absence— If I arrive within one week after this reaches you, I hope you and Gov. Seward will not consider me in the list of deserters and subject to the penalties.

Norman B. Judd to President Abraham Lincoln — October 17, 1863 (emphasis added)

Here, Norman Judd joked about being considered a deserter from his post in Berlin for briefly returning to the United States. As we know, the subject of desertion would be a matter of life or death for his son not too long after he mailed this letter to the President.

Norman, Adelaide, and Frank Judd arrived in Washington D.C. in November 1863. While Lincoln seems to have not ensured that Frank R. Judd received a midshipmen’s commission, he instead appointed him to West Point – an arrangement that I imagine was more than satisfactory to the Judd parents.

The troubled military career of Frank R. Judd

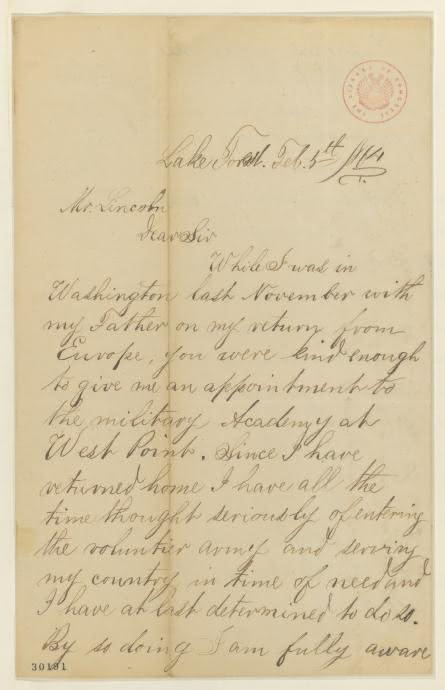

We know that Frank R. Judd did not attend West Point. On February 5, 1864, Frank R. Judd himself wrote a letter to then-President Lincoln explaining his decision:

While I was in Washington last November with my Father on my return from Europe, you were kind enough to give me an appointment to the military Academy at West Point. Since I have returned home I have all the time thought seriously of entering the volunteer army and serving my country in time of need and I have at last determined to do so. By so doing I am fully aware that I lose my chance at West Point but I thought I would ask you to confer a favor on me, by giving the appointment to Richard de Long Stokes a son of Capt Stokes of the Chicago board of Trade battery who is himself a graduate of West Point and it his hearts desire that his son should go through the Academy.

Frank R. Judd to President Abraham Lincoln — February 5, 1864

Frank R. Judd defied his father’s advice and turned down Lincoln’s favor of appointing him to West Point, all the while recommending a friend in his stead. We know that Frank did, almost immediately, enlist as a volunteer in the 8th Illinois Cavalry in February 1864.

Lincoln, Abraham. Abraham Lincoln papers: Series 1. General Correspondence. 1833 to 1916: Frank R. Judd to Abraham Lincoln, Friday,West Point appointment. February 5, 1864. Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://www.loc.gov/item/mal3019100/.

Norman Judd had entrusted his affairs in the United States to a man by the name of Luther Rossiter. Rossiter had become aware of Frank Judd’s decision, and he wrote to Lincoln on February 11:

I understand that [Frank Judd] has joined the eighth Illinois cavalry as a private, hoping you would promote him to some office in the regular army. I believe also he has written you concerning his appointment at West Point. I hope you will take no action in relation to it till you hear from his father.

Luther Rossiter to President Abraham Lincoln — February 11, 1864

It appears likely that Rossiter had not yet conferred with Norman Judd, who had long since returned to Germany, as of the February 11 letter. However, when Rossiter wrote to Lincoln again on February 27, there was no doubt as to Norman Judd’s position on the matter. Here, Rossiter alerted Lincoln that Frank Judd was on his way to Washington D.C. as part of the 8th Illinois Cavalry and:

If he should ask you for the loan of money, you would confer a favor on his father by refusing him in toto.

Luther Rossiter to President Abraham Lincoln — February 17, 1864

We can infer that Norman Judd was not pleased with the state of affairs.

(I previously published an article 1851 letters from Abraham Lincoln turning down a his half-brother’s requests for money, and in so doing, explaining his views on the value of hard work and earning one’s own money before asking for help.)

On September 15, 1864, Frank Judd wrote a letter to a certain R.S. Chilton, requesting that the latter convey two letters of his, one to Lincoln and another to Massachusetts Governor John Albion Andrew, requesting a commission in the army. Perhaps foreshadowing the telegram that Lincoln would write on Judd’s behalf several months later, Judd provided specific instructions in his letter:

It would be necessary that such letter should be for one Frank Judson as it is under that name that I was foolish enough to enlist. If you could do this for me I should be forever grateful and you would never have cause to regret it.

Frank R. Judd to R.S. Chilton — September 15, 1864

Chilton sent the letters that Frank Judd had requested to Lincoln’s personal secretary, John G. Nicolay, on September 21, 1864, in which he stated that he “had reason to think” that both Norman Judd and Lyman Trumbull would support Frank receiving a commission.

(Note: I was not able to ascertain the exact identity of Chilton with confidence, but please do send an email if you have more information on this matter – for it may be valuable in informing us on whether Norman Judd and Trumbull were possibly, if not likely, aware of the request.)

Regardless of whether Norman Judd knew about or sanctioned his son’s September 1864 request for a commission or whether the request was granted , we know that Frank Judd deserted soon thereafter. At the time of his desertion, he had been presenting himself as “William Stanley” in lieu “Frank Judson” or his real name.

Pursuant to Lincoln’s instructions, Frank Judd’s military trial for desertion proceeded. He was found guilty and sentenced to death, but his sentence was suspended. Lincoln would ultimately spare Judd’s life, preventing his execution. While I do not know the exact dates of these subsequent events, Find a Grave reports that Frank Judd deserted on January 28, 1865, which sounds like a plausible date for when he was adjudicated to have deserted on the face in light of Lincoln’s December 29, 1864 telegram.

Aftermath

Lincoln was assassinated within four months of sending his December 29, 1864 telegram regarding Frank Judd.

Norman Judd’s political career continued after his assignment in Prussia ended in September 1865. He served for two terms as a member of the United States House of Representatives (1867-71) and then briefly as collector for the port of Chicago pursuant to an appointment by then-President Ulysses S. Grant. Norman Judd died in 1878.

On April 14, 1882, the Saint Paul Daily Globe published a report published the following report on Frank Judd:

Frank R. Judd, of Chicago, son of S.B. Judd, ex-minister to Russia, was declared insane yesterday and sent to the asylum. He was interested in a lead mine in Colorado, and contracted lead poisoning, causing paralysis on one side of his body and brain. Friends expect to cure him.

(Note: Newspaper erroneously wrote that Norman Judd was Minister to Russia instead of Prussia.)

From that single story, it appears that Frank Judd’s life continued to be eventful – sometimes in unfortunate ways – after his life was spared by Lincoln’s intervention on his behalf. Frank Judd passed away on September 17, 1887.

Conclusion

Frank Judd bore great concerns for his son in Germany, and earnestly hoped that the environment provided by military training would benefit the young man. Lincoln acquiesced to the spirit of Judd’s request, providing for Frank’s admission into West Point despite there seeming to have been little to recommend such an appointment other than his father’s earnest request. Rather than accept the favor and attend West Point, Frank Judd volunteered to serve in the Civil War ,Unsatisfied with being an ordinary soldier, he sought another favor from Lincoln in the form of an officer’s commission. The exact circumstances behind Frank Judd’s desertion are unclear, but it is clear that Lincoln’s intervention likely resulted in his life being spared.

Somewhere in the neighborhood of 300 soldiers on both sides of the conflict were shot or hanged for desertion. Lincoln made no secret of the fact that he was “not willing” to see Frank Judd executed because Judd was the son of one of his closest friends. The 1882 newspaper report on Frank Judd’s being committed to an asylum after suffering from lead poisoning was less than reassuring, other than the note that he had friends who hoped to see him well. Ultimately, I hope that Frank R. Judd was able to make something positive of the second chance he was given thanks to the efforts of his father and a United States Senator and the personal intervention of President Lincoln.