On October 5, 2006, a new anime series called Asatte no Houkou began airing in Japan. The series was eventually localized by Sentai Filmworks with the admittedly cumbersome title Living for the Day After Tomorrow. The unassuming series, produced by studio J.C. Staff, was based on a short manga series of the same name by J-ta Yamada. It is a Big-style age-swap story in which a young girl named Karada Iokawa, who is in the care of her older brother, Hiro Iokawa, suddenly turns into a young woman. Conversely, Shouko Nogami, Hiro’s ex-girlfriend who had just returned from studying in the United States, simultaneously turns into a young girl.

Living for the Day After Tomorrow has long been one of my favorite TV anime pieces, in part because of its story but more for its aesthetics. Despite being 18 years old, I dare say that no anime better captures the essence of summer in audio-visual form as well as it does. Having broached the subject of anime being made by its aesthetics in an initial look at a 2024 series called Days with my Stepsister, I thought it would be a good time to look back at an old, now-obscure, but always a quintessentially summer (despite airing in the fall 2006 season) anime, Living for the Day After Tomorrow.

Living for the Day After Tomorrow Introduction

Living for the Day After Tomorrow is the official English language title of Asatte no Houkou. The anime originally aired in Japan for 12 episodes from October 5, 2006 to December 21, 2006. The anime is an adaptation of a five volume manga by J-ta Yamada which was serialized from March 3, 2005 to June 15, 2007. I have not read the manga – which in any event was never officially licensed in the United States – but I understand from external sources that, while it shares the same set-up and main characters with the anime, there are significant differences in how the central conflict is resolved. This divergence is likely owed in part to the fact that the anime was created in its entirety while the manga was ongoing, and its creators opted to go with an original ending instead of following the manga, which would have forced an ending in medias res. From what I read, the manga ultimately went in some significantly darker directions than did the anime (This 2015 review details some of the differences between the anime and the manga, but note that it comes with anime spoilers and I would thus recommend watching the show before reading.)

Asatte no Houkou was produced by studio J.C. Staff. It was directed by Katsushi Sakurabi, written by Seishi Minakami, and the music was handled by Shinkichi Mitsumune. The North American license is held by Sentai Filmworks and it is currently available for streaming on HiDive. The anime was originally licensed for release in North America in 2010.

(You can see the Japanese websites for the show from TBS (the channel it aired on) and studio J.C. Staff (archived).)

You can find more information about Living for the Day After Tomorrow on the Anime News Network Encyclopedia, AniDB, My Anime List, and Wikipedia. In addition to these sites, you can read other (shorter) reviews of the show on Anime News Network, THEM Anime Reviews 4.0 See also Tim Jones of THEM ranking it as his 11th favorite anime of the 2000s), Moonlitasteria, and The Nihon Review (archived).

Synopsis

Living for the Day After Tomorrow revolves primarily around three characters. The first character we meet and the one I would describe as the primary view-point character, at least in the first half of the show, is Shouko Nogami, a 24-year old woman who had just returned to Japan after studying abroad. In the opening scene, she encounters Karada Iokawa, a 12 year-old girl, who is making a wish using a wishing stone by the roadside.

Shouko joins Karada in making a wish when Karada’s older brother, the 27-28 year old Hiro Iokawa, arrives to pick her up. Shouko and Hiro recognize each other. While they initially tell Karada that they were acquaintances in the United States, the show quickly reveals (albeit not to Karada) that Shouko and Hiro had been in a relationship after meeting in college in the United States. Four years prior to the start of Living for the Day After Tomorrow, Hiro took what he told Shouko would be a brief trip back to Japan for his parents’ funeral. However – he never returned, instead staying in Japan and breaking up with Shouko in the form of a cryptic letter.

Unaware of the complicated backstory, Karada invites Shouko to join her, Hiro, and two others for an already-planned beach trip in a few days. Shouko, for reasons unknown even to her, accepts the offer. At the beach they are joined by the Amino siblings. Tetsumasa “Tetsu” Amino is Karada’s classmate who looks old for his age (unlike the diminutive Karada who looks young), and he is obviously smitten with her. Touko Amino, Tetsumasa’s older sister, is a young woman who runs a local café frequented by Hiro.

The beach trip starts innocuously enough, although Shouko responds with some irritation when Touko, who is aware that she is Hiro’s ex-girlfriend, mistakenly believes that she had followed Hiro to Japan (Shouko had made clear in an earlier scene that she moved to the town in the hope of being able to start fresh in a place where no one knew her).

We learn in several interactions that Karada is sensitive about being seen as a kid. In a moment of frustration, Shouko tells Karada that she looks cute like a child in the bows that Hiro had bought for her, creating an awkward atmosphere.

On the way back, Hiro sends Karada home ahead of him and Shouko. Hiro and Shouko for the first time discuss – however indirectly – what had happened, before Shouko slaps Hiro and runs off when he asks if she still loves him.

She happens to run by the wishing stones, where she sees Karada again making a wish (Karada went to the stones instead of going home). Then, mysteriously, Karada physicallt transmogrifies into a young woman and Shouko into a child about the size of Karada before her transformation. Note that this is not a Freaky Friday body swap – Shouko and Karada are still themselves, just appearing physically younger and older respectively.

As one may imagine – the age swap situation creates a series of problems. Karada initially has an identity crisis. Shouko, who is impressively calm and level-headed despite being flummoxed by the state of affairs, takes Karada home with her while she contemplates what to do. Hiro panics when he returns home to an empty house. He calls Amino, who becomes understandably worried that the young girl he likes appears to have disappeared.

Living for the Day After Tomorrow subsequently proceeds in a way that can be roughly broken into four story arcs. As an initial matter, Shouko has to get some basic affairs in order – which requires coaching Karada on how to take care of some clerical tasks that Shouko could not perform in her current body of a child. In the interim,

Shouko – who initially declined to take Hiro’s call for want of an idea of how she would explain the state of affairs, had to mull over how she would eventually confront Hiro with the situation and force Hiro to accept it – regardless of her own complicated, largely negative feelings about him. Amino spent his time neglecting his studies and frantically looking for Karada.

Once Hiro comes to accept the reality of the circumstances due in large part to the efforts of Shouko, we have a few episodes where she, Hiro, and Karada work together on navigating the odd age-swapped circumstances. Meanwhile, Tetsu, who is not entirely filled in, continues to doubt the neat story offered by Hiro about Karada staying with relatives. The latter stages of the second half of the show, which is beyond the scope of a spoiler-free review, deal with the consequences of withholding important information, especially when the context in which the information is withheld and the discovery of the information hits very close to a certain character’s preeminent insecurity.

The Highlights

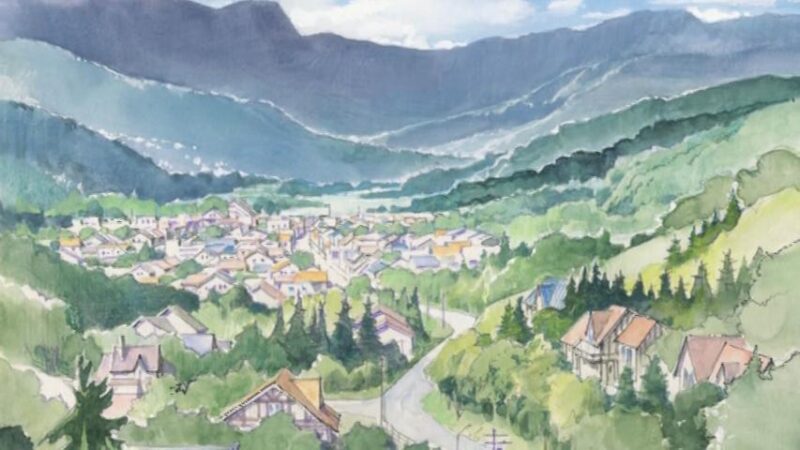

Visual Aesthetics: Living for the Day After Tomorrow is a simple but beautiful visual effort with its striking watercolor backgrounds, expert shading, and distinct earthy tones for flashback scenes. It makes as expert the use of lighting as any TV anime, and certain important scenes are drawn with special care – notably extra detail in character faces and attention to shadows. It is the quintessential summer TV anime. The character designs are solid, albeit not as memorable as the overall aesthetic. Mini Shouko is the most expressive character of the cast – which is somewhat ironic given that she is generally morose. Hiro looks disheveled despite being a gainfully employed pharmacist, but there is story-significance to his appearance. Young Karada’s head is drawn way too big for her body, but her adult form is well designed. Tetsu is a bit generic but his design gets across the point that he looks older than he is.

Animation: Living for the Day After Tomorrow is not heavily animated – it makes ample use of cuts in conversations and portraying its characters moving against static backgrounds. On the flip-side, the characters are always lively – you will never catch a character dead to the world in a conversation. Careful viewers will note that the show pays careful attention to eye contact and gestures. The vast majority of scenes only feature a small number of characters, but the show made an effort to breathe life into background characters when necessary, most notably in episodes 4 and 8.

Audio: Living for the Day After Tomorrow knocks the audio out of the park even more than the visuals – Mr. Shinikchi Mitsumane deserves a big hat-tip here. You can listen to a good part of the sound-track on YouTube. The background music is almost entirely keyboard-based, but there is not a bad background track in the bunch. There are not many background tracks, even compared to some of the relatively short visual novels that I reviewed for my al|together project, but each one is excellent and the anime does a great job of mixing up the tracks within each episode and choosing the correct one for each scene. In addition to the music, the show is permeated with the sounds of summer – from well-placed cicadas to the intersection of the music and the lighting.

The Gimmick: Shouko’s and Karada’s age swaps drive the drama in Living for the Day After Tomorrow. The show never leaves any doubt that the wishing stones caused the swap. Karada admits to having wished to become an adult. The show is less inclined to show its hand on why Shouko turned into a child – albeit there are indirect hints dropped starting in the early episodes. Looking too closely at how the characters react to Karada’s “disappearance” and some other points about Karada will reveal some cracks, but all in all the show does more than one would expect in trying to portray realistic reactions to a very unrealistic state of affairs.

The Characters: Shouko stands out as not only the best character in Living for the Day After Tomorrow, but one of the best characters one will find in any TV anime. Karada is likable and the show never forgets she is a little girl even when she physically transforms into a young adult version of herself. However, there is no escaping the fact that the show is less interesting in sections when it focuses primarily on Karada and Tetsu (more on him in a moment). Hiro makes a poor first impression (by design), but his reuniting with Shouko and navigating Shouko’s and Karada’s age swaps leads to some well-done character growth. Tetsu is a net minus on the whole – his young love for Karada is obvious, and the show justifies his suspicions about her whereabouts, but he can be grating and the show struggles when it shifts to his perspective in some later episodes. One sign that Tetsu is a weak character compared to the main trio is that in order to support his actions and development he needs two characters – his adult (and generally under-utilized) sister Touko and an anime-only character a couple of years older than him named Kotomi Shiozaki as means. I was not surprised when I learned that Kotomi was anime-only because it was obvious she was used to help keep the plot moving at certain points. The show ended up in an odd place with the Kotomi character when it tried to give her some minor character development without fully following through or giving her enough of an independent role to justify it. There are a couple of notable characters introduced late in the show which also feel a bit incidentally convenient – but the particulars are beyond the scope of this review.

The Progression: Living for the Day After Tomorrow is a great anime for its first 7 episodes; I would be hard-pressed to come up with a long list of shows that have a better stretch of the same length. Unfortunately, there is a clear quality dip in terms of story-telling in its final third, caused in part by dragging out an event longer than justified and in part by shifting the focus to Tetsu for large swaths of episodes 9-12. The final episode inherits some of the issues that bedevil the final arc but, to its credit, it lands a solid conclusion that is well-earned for the main characters – all the more impressive knowing that the conclusion is anime-original.

The Review

I was inspired to write about Living for the Day After Tomorrow because it is a beautiful show – so we might as well start there. As I noted in the highlights, I am a big fan of its use of watercolor backgrounds, colors, and lighting to perfectly depict summer in a small town in Japan – and it has one of my all-time favorite anime soundtracks to complement the visuals.

The characters do not stand out as much as the overall art direction, but they are all very expressive – Shouko and the comparatively minor Touko stand out for their strong designs and expressiveness. While it lacks the spectacular computer and CG-aided highs of big budget modern productions, I dare say that Living for the Day After Tomorrow is even more visually appealing today than when it was first released in 2006. I found it refreshing when I first watched it in 2010 and more so now. It certainly was not the end of an animation era, but it came close to it – and the show has a certain visual charm that is unlikely to be fully recaptured by a more modern production. Regarding the voice acting, I single out Ms. Shizuka Ito for an excellent performance as Shouko Nogami – especially in distinguishing Shouko’s adult and child voices.

In considering why Living for the Day After Tomorrow was never especially popular (at least that is my impression), I will concede that its first episode, while well done and ultimately important, does not give viewers a clear and distinct idea of what to expect. As a general matter, the show gives viewers the feeling of watching characters more than being them, but there are numerous instances when we are allowed to see the world through the eyes of either Shouko or Karada. The first episode is largely Shouko-focused. We follow her as she meets Karada at the wishing stones and join her in making a wish. We see her shock when Karada runs up to her ex-boyfriend from America. The show gives us access to Shouko’s monologue when she wonders why she agreed to accompany Karada and Hiro to the beach. Then, after Shouko’s one unfortunate moment of childishness toward Karada and justified irritation directed at Hiro, we see her and Karada swap ages at the very end of the episode. The set-up is important because it gives viewers an idea of where adult Shouko and child Karada were right before their age swaps, and Karada’s beach interactions with Tetsu prove to be especially important later in the show. However, one could forgive viewers for being unsure what the show is going for based on the first episode.

Living for the Day After Tomorrow settles into a pleasant rhythm beginning with the second episode. Karada goes through some genuine initial anguish when her wish to become an adult is granted in a sense, but once she recovers from the shock enough to be functional again – we see that she is still the same sweet girl we saw in the first episode – just trapped in the body of a young woman. Shouko proves to be very much the adult even in her child mode – staying calm in front of Karada and taking advantage of the time when Karada is asleep to figure out how they were going to navigate their new circumstances. Day After never overtly plays the age swap for laughs, but the second and third episodes provide some incidental comedy in watching the responsible-but-sheltered Karada try to function as an adult with Shouko’s coaching while Shouko struggles to understand what Karada does not understand.

The show’s first major task is handling their reunification with Hiro – and it passes this test with flying colors. Shouko, who had moved to the town in the hope of starting over and very much did not expect to see the ex-boyfriend whose shadow had haunted her life for several years, is thrust in the position of not only explaining what has happened to his sister and her, but bridging the divide between a shocked and skeptical Hiro and and his emotionally fragile sister, trapped in an adult’s body.

Much of the first third of the show focuses on this issue – and it is excellent, culminating with a plausibly presented (and beautifully rendered) resolution. Day After continues its strong run as Shouko, Karada, and Hiro figure out how to get along together, Hiro and Karada try to interact normally under odd circumstances and Shouko, with her complicated feelings, stays with her ex-boyfriend and new friend to support them in spire of some obvious limitations in her child form.

Episode 5, which focuses on child Shouko, is excellent and the most charming episode of the entire show. Episode 6 turns its attention to Karada and, while not as strong as 4-5, it presents the best depiction of summer in a TV anime.

Episode 7 is the stand-out episode of Living for the Day After Tomorrow, containing both its finest moment and, with its ending, the beginning of the relative decline of the show.

For spoiler-avoidance reasons, I cannot say much about episodes 8-12 other than that I think they are clearly weaker than episode 1-7. They center on Karada’s particular insecurities. The set up is clever and in line with the show’s emphasis on the main characters inadvertently hurting each other by not being fully honest and forthright and making assumptions about the feelings of others. Episode 8 is not as enjoyable as 1-7, but it would have been justifiable as a one-off.

My issue was ultimately more with episodes 9-12. Karada temporarily resolves an issue she has in episode 8 – admittedly somewhat conveniently and with the introduction of two hitherto unseen characters. Karada then joins Shouko and Hiro in the background while the show’s focus changes to Tetsu.

Tetsu is not a bad character in a vacuum, but he is not interesting. Shouko and Hiro have interesting adult problems, which I will discuss further down. Karada has understandable problems given her particular circumstances and some well intentioned but ultimately questionable decisions made by Hiro. While the show does note that Tetsu has some issues with being mistaken for being older than he is, his character is only meaningfully defined by his affection for Karada. Despite the fact that Tetsu ascends to the status of a main character in the final arc, it is hard to pinpoint where he undergoes any meaningful character development. While the show justifies Tetsu’s suspicions that Hiro is not being entirely forthright about Karada’s whereabouts, he has a tendency to come off as bone-headed despite being directionally correct in his concerns. The script ended up having to devote two characters – Tetsu’s older sister Touko and his friend Kotomi – to doing little other than keeping his search for Karada going.

Moreover, to the extent he is in love with Karada – Tetsu, like Karada, is 12. While there are successful middle school anime romances such as Tsuki ga Kirei, Teasing Master Takagi-san, and The Dangers in My Heart, Tetsu’s love for Karada just is not very interesting, especially when it is explored in parallel with the mature Shouko-Hiro dynamic. I dare say the great 2007 movie 5 Centimeters Per Second did more to make a compelling case why a boy and girl developed strong feelings for one another in a single 3-minute flashback than Living for the Day After Tomorrow was able to do for Tetsu in 12 episodes.

The Tetsu-centric episodes 9-11 have their moments – notably a few important scenes centered on Hiro and Shouko. Karada is still charming and for all my qualms with Tetsu, his heart is in the right place in the anime. But on my re-watch, I came away with the feeling that the script got itself in trouble trying to suddenly support Tetsu as a major character.

While the final episode (12) has some of the issues of episodes 9-11, it does, as I noted in the highlights, end with a strong and well-justified conclusion. It gives Tetsu his moment, but more importantly it provides meaningful endings for the real main trio – Shouko, Karada, and Hiro. Even Kotomi, who exists largely to support Tetsu’s plot-line, finally plays an important role that was cleverly and subtly foreshadowed several episodes earlier.

Shouko is the stand-out character of Living for the Day After Tomorrow. We meet her as she returns to Japan in order to, in her words, start over, after having spent several years (at least four, but most likely six given her age) studying in the United States. The show leaves no doubt that Shouko is intelligent, and she appears to be self-sufficient and well put together (so long as she does not need to cook).

But Shouko is deeply lonely and unhappy – which is obvious from how she carries herself and made explicit in her internal monologues. We learn from Shouko herself that she has no friends and has always struggled getting along with others. To be sure, she is naturally introverted to a point, but Shouko feels like people misunderstand her and assume based on appearances that she is unsocial (note: Shouko is not portrayed as being unusual in any obvious way like, for example, Kimi ni Todoke’s Sawako Kurunoma). She is aware that it is possible, if not likely, that some of her struggles making friends may be on account of her own manner and personality. All of this provides important context for how she sees and responds to Hiro four years after he broke up with her in the form of a letter without a forthright explanation. Shouko has well-founded bitterness regarding how Hiro handled the breakup, but her overall circumstances are also relevant to understanding her feelings. Hiro, who Shouko had strong feelings for, left her in the United States when she had no one else to rely on, and while Shouko already had the tendency to wonder whether her loneliness was due to her having some inherent defects. All of these factors are ultimately relevant to the peculiar circumstances Shouko finds herself in, but she takes a good long while to confront that issue.

Shouko admits to being drawn to Karada at the wishing stones in the first scene of the anime. She ends up feeling some unjustified resentment toward Karada when she figures out that Karada had been the reason Hiro why broke up with her (note that Hiro had never mentioned having a sister to Shouko) and failed to return as promised. But Shouko sets her complicated feelings aside when she has to help Karada after their respective age-swaps, and she quickly comes to like Karada (Karada is sweet and earnest, so it is not hard to see why). Much of Shouko’s emphasis in trying to make Hiro understand the age-swap situation is to help Karada. Shouko is obviously touched when Karada makes it clear that she likes her. Shouko’s relationship with Hiro remains awkward for much of the show – on one hand she comes to appreciate how much Hiro cares for Karada, but she is still unhappy with how Hiro broke up with her and his continued unwillingness to confront his past actions.

Before moving away from Shouko – I will add that she is the source of the best comedy in Living for the Day After Tomorrow. There are little moments of humor in Shouko, a morose 24-year old woman who barely smiles in the first episode, suddenly having to navigate life as a little girl. Shouko sometimes forgets that she appears to others to be a little girl – and these moments tend to be more amusing than when Karada forgets that she looks like an adult. Better yet are the moments when Shouko takes advantage of her circumstances. Episode 5 is fun for that reason specifically, but there is a moment in the final episode where Shouko plays up her age-swapped part with a wink and nod that one would not have thought she was capable of earlier in the show – a funny moment with some deeper meaning for people who have enjoyed watching her journey.

Karada is a more straightforward character than Shouko. She sees herself as a burden to Hiro – and there is a particular reason for this that has to do with their particular circumstances, which I will mark as beyond the scope of this review. It is because Karada thinks she is a burden that she wants to grow up and be self-sufficient.

Apart from her specific wish to become an adult, we see that Karada is good at cooking and earnest about chores for the same reason she wanted to grow up quickly. There are two clever subtle points with Karada that I will highlight without veering into undue spoilers. Firstly, while Karada is not portrayed as being unusually intelligent or sharp, she is more than capable of picking up on things around her. For example, while we can see that Hiro loves Karada and chose to re-orient his life to support her because that was what he wanted to do, Karada picks up on some real things about how Hiro carries himself day-to-day which gives her a rational basis for believing that she is a burden on him. Secondly, Karada is a very honest girl – and while this is certainly a good quality, it also makes her sensitive to deception.

Hiro’s character is not fully established until the later stages of the show – but I ultimately found him interesting. While the show never asks us to doubt that he made the correct decision in prioritizing Karada over his former relationship with Shouko, it also never asks us to doubt that he broke up with Shouko in a cowardly way and caused her lasting damage.

While Hiro loves Karada and takes good care of her, the show makes clear that her doubts and insecurities are tied to some of his own decisions and his manner allows her to pick up on a whiff of depression. Hiro appears to be more outgoing and socially functional than Shouko, but he has a tendency to assume how his actions will affect others instead of taking the time to understand their perspective. Hiro’s life is changed first by his unexpectedly being reunited with Shouko and seeing how miserable she is and secondly by Karada’s and Shouko’s age swaps. These circumstances force Hiro to eventually deal with the consequences of some of his life choices. To the show’s credit, Hiro shows subtle-but-strong character growth and, like Shouko, is in a much better place by the end of episode 12 than when we first meet him in episode 1.

The other side characters exist largely to support the main trio plus Tetsu. I will note that I found Touko Amino, Tetsu’s older sister and Hiro’s friend,, to be a fun character in her small number of scenes – and I wish that the show made more use of her with respect to Hiro. Limiting her to supporting Tetsu’s side-plot was a waste.

Both the opening and ending songs and animation are strong – and I enjoyed them more on my re-watch than I recall having originally liked them in 2010. The opening song is Hikari no Kisetsu by Suara and, in the show’s distinctive visual style, features Karada (pre-transformation) going about her day-to-day life (see OP video). The ending song is Sweet Home Song by Suara and also features young Karada, albeit her running along train tracks and hopping over puddles instead of going about her life (see ED video). The ending has the slightly better song but the opening has the better of it with its much more interesting and dynamic visuals.

Review Conclusion

Living for the Day After Tomorrow would be worth watching for its aesthetic qualities even if it were an otherwise mediocre piece, similar to my final assessment of the more recent Days with My Stepsister. Readers of The New Leaf Journal will know that I appreciate crisp depictions of the seasons. Living for the Day After Tomorrow is not the only anime to get a season just right – Kanon, which began in the same fall 2006 season, still has a claim as the best winter anime, but nothing in the TV realm handles a season as well as the summer of Living for the Day After Tomorrow.

It is fortunate that Living for the Day After Tomorrow is a very good anime with great aesthetics instead of an anime that needs to be carried by instead of enhanced by its aesthetics. The story is well-conceived and Shouko – whose background and issues are unusual for an anime character – is a major selling point. The first 7 episodes are great, with episodes 4, 5 and especially 7 being episode of the year quality. Even granting some unfortunate choices and points of emphasis in episodes 8-12, Living for the Day After Tomorrow is still one of the better TV anime seasons to air in the 2001-2010 decade.

Were one to ask me for an underrated anime – Living for the Day After Tomorrow would be the first that came to mind, both on account of my enjoyment of it and my being under the impression that it has never received much recognition one way or another. I submit this review in the hope that some readers will give it a chance and come to appreciate it more today than when it was first released. As I opined in an article about aesthetics in the winter 2024 series A Sign of Affection, I doubt that the visuals of any 2006 anime have aged as well as those here.