1953 years ago to the day, on April 16, 69 AD, Otho, the short-lived Roman Emperor, committed suicide in lieu of persisting in a civil war to retain the throne that he had held for four months against the armies of Vitellius. 87 days after securing the throne by murdering Galba, the previous Emperor, the reign of Imperator Marcus Otho Caesar Augustus ended by his own hand. The story of Otho is a complicated one. Although he was reviled by many of his elite contemporaries in life for his profligate spending and obsequiousness toward former Emperor Nero, a number of his harshest critics begrudgingly respected his decision to end his own life rather than to continue his civil war. As we know with hindsight – Otho’s suicide would not end the Civil War. Almost immediately after Otho’s demise, armies in the East declared for Vespasian, the Governor of Syria. With the support of many of Otho’s loyal legionaires, the armies of Vespasian marched on Rome in December 69, murdered Vitellius, and thus ended the civil wars of 68 and 69 once and for all.

I examined the complex life and death of Otho in an 18,000-plus-word article last April. Today, to mark the 1,953rd anniversary of Otho’s death, I will focus on one of the accounts of his death that I covered in brief in last year’s post. Unlike the Roman historians, Martial, a Roman poet, is not known to have expressed negative views of Otho. Martial was a young man during the wars of 69, and thus had lived through Otho’s brief reign and demise. While we will never know the entirety of Martial’s views on Otho, it seems clear from one of his epigrams that he greatly respected Otho’s decision to take his own life. I will re-print the original Latin epigram with two different translations below.

Martial’s Epigram on Otho

First, I will reprint Otho’s epigram in Latin:

Martial’s Epigram On Otho in Latin

Cum dubitaret adhuc belli civillis Enyo

forsitan et posset vincere mollis Otho

damnavit multo staturum sanguine Martem

et fodit certa pectoria tota manu.

sit Cato, dum vivit, sane vel Caesare maior:

dum moritur, numquid maior Othone fuit?

While I did take introductory Latin in college, I will defer to far more learned translators to bring you Martial’s epigram on Otho in English. You will find three translations below.

Bohn’s Classical Library Translation (1897)

While Bellona yet hesitated as to the result of the civil war, and the gentle Otho had still a chance of gaining the day, he looked with horror on a contest which would cost great bloodshed, and with resolute hand plunged the sword into his breast. Grant that Cato, in life, was even greater than Caesar; was he greater in death than Otho?

Link.

F.A. Wright’s Translation (1924)

She wavered yet, the fury of our fray, And wanton Otho still could win the day; But cursing war with all its price of blood, He pierced his heart and perished as he stood. Let Cato's life than Caesar's greater be: But in ther death is Otho first or he?

Link.

Loeb Classical Library (1993 ed)

Although the goddess of civil warfare was still in doubt, and soft Otho had perhaps still a chance of winning, he renounced fighting that would have cost much blood and with sure hand pierced right through his breast. By all means let Cato in his life be greater than Caesar himself; in his death was he greater than Otho?

Link.

Assessment

Translations

The 1897 Bohn’sand 1993 Loeb translations of the Epigram are substantially similar – differing more in phrasing and a few word choices than they do in content.

One notable difference between those translations and F.A. Wright’s 1924 translation is the handling of the word mollis.

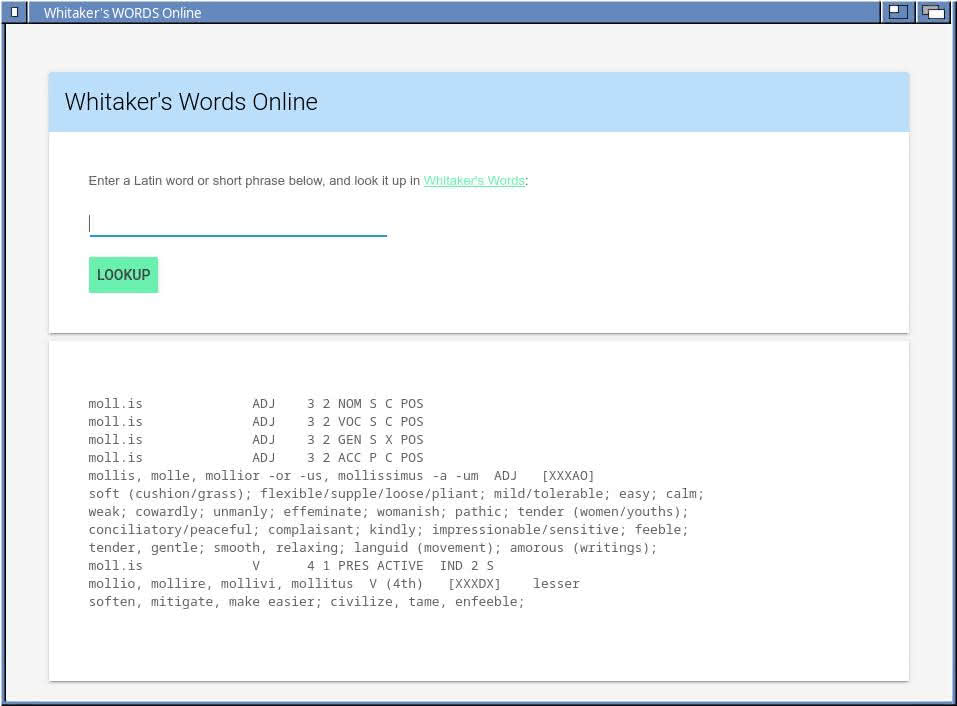

Loeb translated mollis as soft while Bohn’s translated it as gentle. Both of those seem in line with the word’s meaning. I am curious why Wright chose to translate mollis as wanton. While Otho was accused of wanton conduct (see his murder of Galba to seize the throne), that does not seem to be a natural translation of mollis, nor does it seem to fit in Martial’s epigram. Both Bohn’s and Loeb translated the word to convey that Martial believed that Otho was not cut out for the battlefield or bloodshed. While that does make sense in context, I am curious if any translators read mollis as meaning effeminate or some derivative thereof in light of the extant accounts of Otho’s great care for his appearance and the pains he undertook to ensure that he never had stubble.

Aside from the translation of mollis, Wright’s take on the poem is almost identical in terms of content and tone to the Bohn’s and Loeb translations.

Martial’s View on the Military Situation

I noted in my comprehensive article on Otho that Otho’s actual military situation at the time of his suicide was a matter of some debate. Otho had just learned that his troops had lost a significant battle at Bedriacum. However, some of the historian accounts took the position that Otho nevertheless had enough loyal men and resources to continue his war against Vitellius. Others have taken the view that Otho’s military situation was more dire.

While Martial’s poem does not take a decisive view on the military situation, it is clear that Martial wrote with the view that Otho could have fought on and potentially won.

Regarding the translations, Loeb takes a more equivocal view of Martial’s meaning that Bohn’s and Wright. The Loeb translation states that “Otho had perhaps still a chance of winning…” the earlier translations left out the perhaps – stating more decisively that Otho did in fact have a chance of winning.

Otho vs Cato

The poem builds up to a strong endorsement of Otho’s decision to take his own life rather than to pursue the war further. Martial set up the conclusion by stating the views that Otho could have credibly continued the war but that Otho decided to take his own life to prevent further bloodshed.

After describing Otho’s decision, Martial segued into the story of Cato the Younger. Cato was a figure in late Republican Rome who sided with Pompey and the Senate in their civil war against Julius Caesar. When Caesar prevailed and it became clear that Cato’s choices were to accept Caesar’s pardon or take his own life, Cato opted for his sword.

Martial grants, arguendo, that Cato was greater in his life than Julius Caesar. There is no doubt that Martial and all of the ancient historians would have granted that Cato was greater in his life than Otho. However, Martial asked a provocative question: Was Otho greater in his death than Cato?

Martial’s question, which concludes his poem, is left unanswered. However, I think that the answer lurks in the Epigram. In Martial’s telling, Cato was great in life for his character and fight for Republican Rome, and he would have been great in death for refusing to cast aside his honor and submit to Caesar. Otho, whatever defects he may have had in life, chose to forego his life and the opportunity to win the civil war and remain Emperor in order to spare his soldiers and the people of Rome from more death. It seems altogether likely and probable that Martial – in this poem, at least – viewed Otho’s final redemptive act as greater than Cato’s.

Conclusion

We are lucky to have a number of historical accounts of the events of the Roman Civil Wars in 69 A.D. and the brief reign of Otho. Martial, being a poet, did not explore and criticize Otho’s reign and life in the same way that the ancient historians did. But in a few lines, he summarized a view of Otho’s final act as a noble death in line with the best traditions of classical Rome. It fits in well with the more detailed histories of figures such as Tacitus and Plutarch.