October, the tenth month of the year, is the first month in two respects. For one, it is the first month of our fiscal year. That “first” does not concern this article. Here, I am more interested in a second “first” for October – it is the first of the two months in the northern hemisphere that take place entirely in the autumn.

With October being the first full autumnal month, many begin to change their wardrobes as the temperatures grow cooler and the days wax shorter. I tend not to be on top of seasonal style changes for two reasons. Firstly, I am neither perturbed by the hot nor cold. Secondly, I almost always wear dress jeans or slacks and a collared shirt, so there is little to change beyond sleeve lengths and adding a jacket when the temperatures call for it.

Since I am not the resident fashionista that my distinguished colleague of many hats, Victor V. Gurbo, is, I must resort to secondary sources to enlighten the audience as to what is “in” this season. I knew that Project Gutenberg has many magazines – a couple of which I used as source material for articles in September. What better place to glean insights into the latest styles than an online repository of books and magazines that are so old that they are no longer subject to copyright laws?

Searching Project Gutenberg For Information About Fashion Trends

Surprisingly, it took me a bit of searching before I came across information on the “hottest” seasonal fashions. I knew my search had ended soon after opening Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, No. V., October, 1850, Volume 1. Harper’s, which continues to this very day as “Harper’s Magazine,” was and is published in New York City. The table of contents for the fifth Harper’s New Monthly Magazine concluded with “Autumn Fashions.” Technically speaking, this New York City magazine promised a section on “autumn fashions.” This is not only what I was looking for, but surely what our fashion-conscious readers are looking for too.

Ladies in Luck; Men Should Just Dress Like Adults

Now, before reporting on what is in for autumn, I must note one minor shortcoming in my fashion source. Harper’s only provided information about women’s fashion for autumn. Thus, if you are a woman reader, consider yourself in luck. If you are man, just put on some clean slacks and a collared shirt, and you will be well. While I wish I did not have to specify “clean,” the number of men outside in wrinkled cargo shorts and sprung tee-shirts that look like they were wrest from the laundry hamper or the bedroom floor compel me to cover all the bases. Come to think of it, there are some increasingly disturbing trends in women’s fashion as well, especially as more people seem to have let themselves go during the ongoing unpleasantness that is the Chinese Communist Party’s latest and greatest export. But I digress, this content is not to harp on problems, but rather to present solutions.

Nineteenth Century Women’s Fashion Guidance: Evening Dresses for Autumn

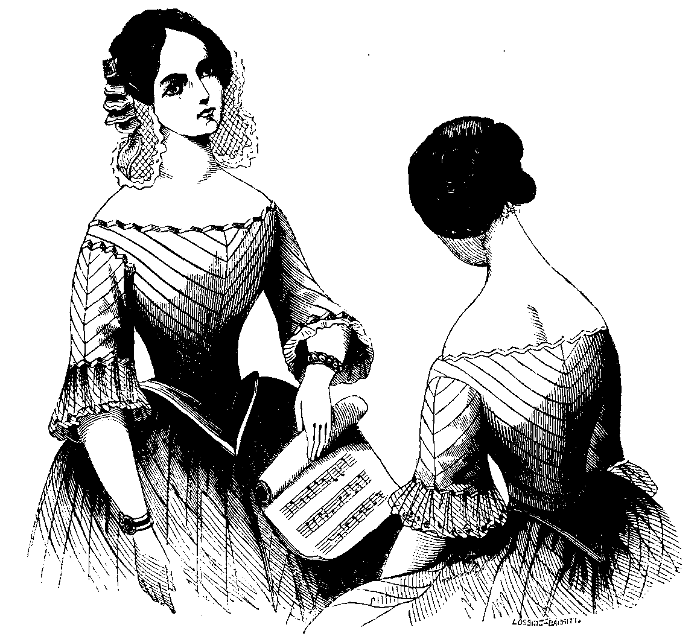

Harper’s began with an introduction to evening dresses for autumn. Below, you will find a picture of the most stylish autumn dresses, followed by my unpacking of Harper’s explanation of the stylish attire.

Harper’s Description of the Evening Dress Illustration

In the following sections, we will examine Harper’s account of the in-style evening dresses in great detail, with in-depth definitions for potentially unfamiliar terms offered as needed. Before that, however, I will reprint Harper’s description of the foregoing evening dress illustration:

“[The illustration] which shows a front and back view. It is a pale lavender dress of striped satin; the body plaited diagonally, both back and front, the plaits meeting in the centre. It has a small jacquette, pointed at the back as well as the front; plain sleeve reaching nearly to the elbow, finished by a lace ruffle, or frill of the same. The skirt is long and full, and has a rich lace flounce at the bottom. The breadths of satin are put together so that the stripes meet in points at the seams. Head dress, with lace lappets.”

We will define some of these terms in the following sub-sections, but allow me to provide a definition for “lappet” here, since it does not appear again in Harper’s content. Webster’s 1913 defines “lappet” as “[a] small decorative fold or flap, especially of lace or muslin, in a garment or headdress.” For the etymologically inclined, Webster’s 1913 attributes the term to the famed English writer, Jonathan Swift.

White is “In” for Nineteenth Century Evening Dresses

The first question one might ask is what color is in these days? Harper’s informs us right from the top that “[w]hite is generally adopted for the evening toilet.” For those of you not down with the vocabulary the kids are using these days, “toilet” here bears the meaning “dress.” Some kids may be wont to render it “toilette” in this context, but other kids would sneer and mock those kids for “trying to sound all French or something.” Or so I heard through the grapevine, maybe.

Nineteenth Century Evening Dress Materials

Having settled on white as the color, Harpers offers a more detailed explanation of the perfect autumn evening dress: “Muslin, tulle, and barege form elegant and very beautiful textures for this description of dress.” All three of these terms refer to different types of cloths used in Harper’s recommended autumnal evening dress. Now, I do not assume that all are as down with the latest fashion vocabulary as I am. For that reason, let us stop to review the key words before continuing.

Defining Muslin, Tulle, and Barege

Webster’s 1828 defined “muslin” as “[a] sort of fine cotton cloth, which bears a downy knot on the surface.” The Century Dictionary, compiled some four decades after Harper’s autumnal fashion expose, offered a somewhat broader definition: “Cotton cloth of different kinds finely made and finished for wearing-apparel, the term being used variously at different times and places.” Before continuing, I must note a fitting usage example from Century courtesy of Henry James’s “A Passionate Pilgrim”: “She was dressed in white muslin very much puffed and frilled, but a trifle the worse for wear.” Harper’s, of course, is recommending evening dresses for autumn that are none the worse for wear, but the example citing a white muslin was too good to exclude from the definition.

What of “tulle”? Century explains that this refers to “[a] fine and thin silk net, originally made with bobbins …, but now woven by machinery.” Pertinent to Harper’s fashion guide, Century noted: “It is used … in dressmaking; it is sometimes ornamented with dots like those in blonde-lace, but is more commonly plain.”

Finally, we again turn to Century for the definition of “barege,” necessary in this instance, for the word was not defined in Webster’s 1828 or Webster’s 1913. Century defined “barege” in the pertinent context as “[a] thin gauze-like fabric for women’s dresses, usually made of silk and worsted, but in the inferior sorts, with cotton in place of silk.” As a bonus for those who are interested in dress fabrics, Century provided a bit of a chronology in its definition of “balzarine”: “A light mixed fabric of cotton and wool for women’s dresses, commonly used for summer gowns before the introduction of barege.” Allow me to retreat to more comfortable terrain – statutory interpretation – and note that from Harper’s decision to include berage in a list of acceptable evening dress fabrics, but exclude balzarine, we can conclude that balzarine is, at the very least, not “in” for evening dresses in the autumn these days.

Nineteenth Century Autumnal Evening Dress Flourishes

Harper’s explains that the evening dresses “in” for autumn “are decorated with festooned flounces, cut in deep square vandykes; the muslins are richly embroidered.” For those not in the know, let us again define some of the key terms. Webster’s 1828 defined a “flounce” in the pertinent aspect as “[a] narrow piece of cloth sewed to a petticoat, frock, or gown, with the lower border loose and spreading.” Webster’s 1828 defined a “vandyke” as “[a] small round handkerchief with a collar for the neck, worn by females.” Festoons refer generally to ornaments with flowers or ribbons, and Century informs us that to festoon means to “adorn with festoons.”

Harper’s continues: “A barege,trimmed with narrow ruches of white silk ribbon, placed upon the edge, has the appearance of being pinked at the edge. Those of white barege covered with bouquets of flowers, are extremely elegant, trimmed with three deep flounces, finished at the edge of a chicoree of green ribbon forming a wave; the same description of chicoree may be placed upon the top of the flounces.” Again for the benefit of those who are tragically less up to date with the latest in women’s fashion, we must define a few additional terms here. A “ruche,” according to Webster’s 1913, is: “A plaited, quilled, or goffered strip of lace, net, ribbon, or other material – used in place of collars or cuffs, and as a trimming for women’s dresses and bonnets.” One may also find this word spelled ‘rouche.” As for “chicoree,” I could not find a single definition unrelated to the endive, but its use in “a chicoree of a green ribbon forming a wave” offers a sound definition in context, and furthermore is in line with what I was able to find in limited search results where I saw “chicoree” being used with reference to women’s clothing.

Nineteenth Century Corsage Styles for Fall

Finally, we reach a term with which the uncultured among us, I mean among you, might be more familiar with: “Corsage a la Louis XV, trimmed with ruches to match.” But lest you think you finally stumbled into familiar territory, I regret to inform you that Harper’s refers not to the wearable bouquet common in American formal events, for the word “corsage” was not used in that sense in 1850. Instead, the term is being used as Century defined it several decades later: “The body or waist of a women’s dress; a bodice; as, a corsage of velvet.” Webster’s 1828 defined a “bodice” as “a waistcoat, quilted with whalebone; worn by women.” Webster’s 1913 added a second, broader definition, suggesting that whalebone was no longer intrinsic to the definition of a bodice.

While we have clarified the corsages at issue, we have yet to explore the reference to Louis XV, who reigned in France from 1715-1774, might be slightly less familiar. Not content to leave us in a state of uncertainty, I endeavored to ascertain the relevance of King Louis XV to our latest autumn fashion trends. I found a page on a fashion history site, hisour.com, devoted entirely to the subject of “Louis XV Style Fashion of Women 1730-1750.” Now over the target, I perused the article for information specific to the corsage of which Harper’s spoke. Luckily, Hisour did cover the corsage in the article: “Most of the dresses of [the 18th century were low-waisted, pointed. Under each dress the women wore a boned body and petticoats. These corsets were essential for getting a small waist and for keeping the shape of the corsages, and the petticoats helped support the baskets under the skirts.”

The passage gets a bit ahead of us at the end; we will be looking at Harper’s skirt recommendations in the next section. But this does give us an idea of what Harper’s was likely referring to in alluding to King Louis XV when discussing corsages. In 1850, the style of French fashion from the mid-eighteenth century would have still been relatively fresh in the minds of denizens of the higher rungs of New York City society.

This better understanding of the Louis XV style of fashion will aid us shortly, when we return to the subject of corsages after gaining an understanding of what types of skirts are in this fall.

Nineteenth Century Evening Dress Skirts for Autumn

Having exhausted the top autumnal fashions for the evening dress’s torso, Harper’s finishes its instructions with a discussion of the skirts most in vogue. Let us begin.

“For dresses of tulle, those with double skirts are most in vogue. Those composed of Brussels tulle with five skirts, each skirt being finished with a broad hem, through which passes a pink ribbon, are extremely pretty.” What is the difference between regular tulle and Brussels tulle? I mightn’t be the top expert in the field, but Oxford dictionary does provide a definition of Brussels lace, courtesy of lexico.com: “An elaborate kind of lace, typically with a raised design, made using a needle or lace pillow.” While the Brussels tulle skirts do sound “extremely pretty,” as Harper’s suggests, I am sure that many fashion-conscious women will be happy to hear that the double-skirt non-Brussels tulle dress is most in vogue, for dealing with five skirts does sound somewhat troublesome.

For those who think that five skirts are better than two, and are willing to put the time in to manage all of those skirts, Harper’s does offer a detailed account of the most fashionable quintuple-skirt dress for the season. “The skirts are all raised at the sides with a large moss rose encircled with its buds, the roses diminishing in size toward the upper part. These skirts are worn over a petticoat of a lively link silk, so that the color shows through the upper fifth skirt.” For those wondering what a moss rose might look like, Wikipedia kindly offers a good selection of pictures of different varieties of the flower.

Aligning Styles Across All Parts of the Nineteenth Century Autumn Evening Dress

Finally, the Harper’s concludes by discussing the relationship between the in-style skirts and the corsage: “As to the corsage, they all resemble each other; the Louis XV and Pompadour being those only at present in fashion.” We already examined the Louis XV style, but what of the Pompadour? The style is named for Madame de Pompadour, the chief mistress of Louis XV for many years. Contrary to its common contemporary usage – insofar as it could be described as “common,” – Harper’s definitely does not refer to a hairstyle. More likely, it refers to something along the lines of the following definition from Webster’s 1913: “[A] style of dress cut low and square in the neck…” Since the Louis XV style appears to have been used solely in connection to the corsage, and now skirt, it seems likely that Harper’s is presenting the Pompadour as the in-vogue style for another part of the dress – the neck – rather than as an alternative style to the Louis XV. If you return to the picture, you will find that the description of the “Pompadour” style does appear to match the necks of the ladies’ dresses. Of course, I could be entirely mistaken – if that is the case, please let me know.

Nineteenth Century Women’s Fashion Guidance: Morning Dresses for Autumn

While I am sure that women readers are grateful that I have cued them into what is “in” for evening dresses this autumn, they might think that I have made a terrible oversight. “Why thank you New Leaf Journal for telling me what to wear in the evening, but what shall I wear in the morning?” Fear not, we would commit no oversight that our nineteenth century shepherds at Harper’s did not, and they did not commit an oversight here. Behold, Harper’s picture of the in-style morning dress for the season.

Harper’s provides the following narration of the above morning home dress illustration: “[This figure] represents an elegant style of body, worn over a skirt of light lavender silk, with three flounces, each edged with a double rûche, trimmed with narrow ribbon. The body is of embroidered muslin, the small skirt of which is trimmed with two rows of lace; the sleeves are wide; they are three-quarter length and are trimmed with three rows of lace and rosettes of pink satin ribbon. This is for a morning costume.”

Thanks to the work we have already done, I only feel compelled to define one word from this description. Webster’s 1913 tells us that a “rosette” is “[a]n imitation of a rose by means of a ribbon or other material…”

In-Style Colors for Nineteenth Century Morning Dresses in Autumn

I will recount Harper’s guidance out of order in order to mirror the order that it presented its analysis of in-style evening dresses. Harper’s makes clear from the top that its illustration and the accompanying description is just one example of an in-style morning dress, not the example. Thus, while “light lavender silk” is in style, that is far from the only color option. In fact, according to Harper’s, “[i]t is almost impossible to state which colors most prevail, all are so beautifully blended and intermixed…” With that being said, the most in-fashion colors “are maroon, sea-green, blue, [and] pensée,” among others. I was not quite sure what “pensée,” a word usually referring to thoughts in English when imported from French, translated to in terms of color. If we are to believe a source contemporary to the fashion trend-watchers of 1850, myperfectcolor.com reports that there is a shade of blue called “bleu pensee.”

Alternative Nineteenth Century Morning Dress Styles for Autumn

Harper’s provided a detailed description of “[a]nother elegant style of morning home dress…” Below, I reprint Harper’s description: “[C]omposed of Valenciennes cambric; the corsage plaited or fulled, so as to form a series of crossway fullings, which entirely cover the back and front of the bust, the centre of which is ornamented with a petit décolletté in the shape of a lengthened heart; the same description of centre-piece is placed at the back, where it is closed by means of buttons and strings, ingeniously hidden by the fullings. The lower part of the body forms but a slight point, and is round and stiffened, which descends a châtelaine, formed by a wealth of plumetis, descending to the edge of the dress, and bordered on each side with a large inlet, gradually widening toward the lower part of the skirt.”

Let us conclude with the possibly-necessary definitions for those readers of less refined taste than Harper’s 1850 audience.

Our Final Set of Nineteenth Century Dress Component Definitions

“Cambric” refers to “[a] thin, and white fabric made of flax or linen.” Webster’s 1913 noted that cambric also referred to an imitation fabric made of cotton, designed to imitate linen cambric. I am not sure what was unique about cambric from Valenciennes, but that region of France is noted for its particular style of lace-work.

“Fulling” in the fabric context, according to Century, refers to “[t]he process of cleansing, scouring, and processing woolen goods to felt the fibers together and make the cloth stronger and firmer.” I can only infer that with ‘crossway fullings,” Harper’s refers to the pattern that the fabric makes over the corsage.

“Décolletté” refers to a low-necked garment. If you return to the illustration of a different illustrated dress, you will see what Harper’s means when it describes the décolletté as being “in the shape of a lengthened heart.” Harper’s notes, of course, that this is also repeated on the back of the dress.

Webster’s 1913 defines a “chatelaine” as “[a]n ornamental hook, or brooch worn by a lady at her waist, and having a short chain or chains attached for a watch, keys, trinkets, etc.” This châtelaine is described by Harper’s as being “formed by a wealth of plumetis, which the modern and contemporary Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary defines as “a fine lightweight dress fabric of cotton, wool, or rayon that is woven with raised dots or figures on a plain background producing a feathery or embroidered effect.” Noting that this definition is far removed from 1850, I think that we can safely conclude that Harper’s was not referring to plumetis made of rayon, but instead of either cotton or wool.

Parting Shots

Fashion has been a seldom-explored topic here at The New Leaf Journal, but I ventured into these lightly-explored waters in the spirit of autumn. While I cannot promise that the women in our audience will have no further work to do in filling their fall wardrobes after studying this content, I hope that at the very least it offered an interesting look at fashions from times gone by, with an ample list of definitions related to fabrics and dress components.