In 1999, I asked for and received a book titled Pokémon: Pathways to Adventure. The book, authored by Mr. Jason R. Rich, was a sort of prototype let’s play – telling the story of a single play-through of Pokémon Red in narrative form while doubling as a children’s adventure book and quasi-strategy guide for the game. I enjoyed reading the book in 1999, but I came away with the view that it failed to the extent that it was intended to be a Pokémon strategy guide. My original copy of the book disappeared from my collection somewhere in the intervening two decades. In early 2020, I purchased a used copy of Pokémon: Pathways to Adventure on Ebay and decided to re-live the adventure anew.

Below, I will offer a critical review of Pokémon: Pathways to Adventure. Are my views of the book as a Pokémon strategy guide different than they were in 1999? (Spoiler: No.)

Technical Details

| Field | Output |

| Book Title | Pokémon: Pathways to Adventure |

| Author | Jason R. Rich |

| Publisher | Sybex, Inc. |

| Pub. Date | March 1999 |

| Pages | 103 |

| ISBN-13 | 978-0-7821-2503-0 |

| ISBN-10 | 0-7821-2503-4 |

| LOC No. | 98-89150 |

| Open Library | Link |

| Goodreads | 922947 |

| Inventaire | Link |

Pokémon: Pathways to Adventure was part of the Pathways to Adventure books, published by Sybex. The Pathways to Adventure series consists of six books, four of which are about Pokémon. The instant book was the first of the four Pokémon Pathways to Adventure books – the latter three covered Pokémon Snap and Pokémon Gold and Silver. The four Pokémon books were authored by Mr. Jason R. Rich.

Book Structure

Pokémon: Pathways to Adventure spans 103 pages and is broken into 9 chapters.

Structure of My Review

It is not often that one reviews a Pokémon children’s book/strategy guide 23 years after it was originally published. For that reason, I do not have a pre-set template for tackling this unusual project.

To begin, I will review the book from the perspective of someone considering its merits in 1999. It was published about six months after Pokémon Red and Blue were released in the United States. While the original Pokémon games were designed to be playable for children as young as six, knowledge of the games and their mechanics is much greater now than it was in 1999. Moreover, the only children in this book’s target age group who would be playing Pokémon Red and Blue today are likely ambitious enough to get through the game without simple quasi-strategy guides.

I will examine Pokémon: Pathways to Adventure in several aspects for this review:

- As a children’s story

- Aesthetics

- As a video game strategy guide

- As an idea

The first part of my review will assess Pokémon: Pathways to Adventure as a children’s adventure book. That is, how the book stands as a story separate and apart from its merits as a practical guide for playing the games.

The second part of my review will tackle the book’s aesthetics.

The third part of my review will be a critical assessment of Pokémon: Pathways to Adventure as a strategy guide for Pokémon Red and Blue. Here, I will consider whether it would have been a useful resource for a child no older than ten.

Finally, I will examine the concept behind the book – building off a primative-looking role playing video game to write an adventure story that is also designed to help young readers beat the underlying game.

Reviewing Pokémon: Pathways to Adventure as a Story

One reason for Pokémon’s immense popularity in 1998 and 1999 was that it was available in various forms of media. The video games – Pokémon Red and Blue versions – were at the center of the Pokémon universe. However, there was also an anime television series, card game, and many other collectibles. I had classmates in my small school who did not even have a Game Boy but who nevertheless enjoyed Pokémon in other ways.

Pokémon: Pathways to Adventure presented itself as more than a video game strategy guide. For example, note the following passage from the back cover:

Journey with Ash as he travels the vast and magical world of Pokémon. Learn his secrets for collecting and raising these extraordinary creatures, and cheer as he defeats rival trainers and outsmarts the sinister society of Team Rocket!

Mr. Rich wrote in the book’s acknowledgements:

I hope you find reading Pokémon: Pathways to Adventure as exciting as playing the Nintendo Game Boy game itself.

From these statements, I come away with the impression that Pokémon: Pathways to Adventure was intended to be enjoyable even for children who do not play the games. Perhaps, in the context of 1998 and 99, it would have been able to give children who did not have a Game Boy the opportunity to experience what the game had to offer without playing it.

Focus on the Story

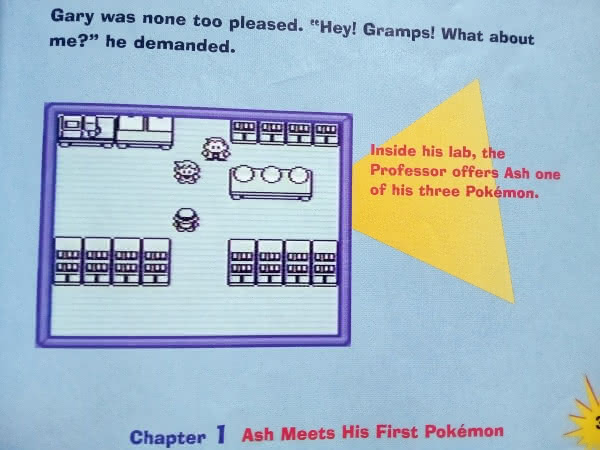

Pokémon: Pathways to Adventure is ultimately a game of Pokémon Red and Blue (Mr. Rich was playing Red) told more in the version of a story than it is an actual strategy guide. Mr. Rich hewed closely to the gameplay throughout the story. Early in the story, Mr. Rich made a number of references to game mechanics – but these references dwindled as the book went on.

Pokémon: Pathways to Adventure includes numerous direct quotes from non-player characters in Pokémon Red and Blue (the player character is a silent protagonist). Mr. Rich added flourishes to illustrate what the player character was thinking at different points in the game.

Mr. Rich named the protagonist of the game (the player character) “Ash” after the protagonist of the anime. While the anime and games are set in different universes (albeit featuring many of the same characters and locations), children closely associated one with the other. Naming the protagonist Ash highlighted the connection.

Pacing Issues

One of the book’s major issues is that I came away with the distinct impression that the writing of the book had come up against time constraints. The story suffers greatly from pacing issues. Pokémon: Pathways to Adventure starts out at a leisurely pace, introducing the dramatic personae and developing the world and its objectives. The story then rushes through the second two-thirds of the game, trying to squeeze too much content into too few pages. Some context is needed to illustrate the issue. The Pokémon games required the player to collect eight gym badges before proceeding to defeat the Elite Four and champion to become champion. While reading, I marked off the pages at which the hero in Mr. Rich’s story collected each of his eight badges:

- Stone Badge (Brock) – page 27

- Cascade Badge (Misty) – page 49

- Lighting Badge (Lt. Surge) – page 52

- Rainbow Badge (Erika) – page 63

- Marsh Badge (Sabrina) – page 76

- Soul Badge (Koga) – page 80

- Volcano Badge (Blaine) – page 86

- Earth Badge (Giovanni) – page 88

The distance between badges is not a perfect pacing metric. Pokémon Red and Blue made it possible to beat the gyms in a large number of orders, and undertaking events in certain orders could lead to beating gyms close together. With that being said, the above list illustrates the book’s pacing issues. There were technical reasons explaining the significant delay between the first and second badges, but after the hero picks up the second badge, the pace of events increases dramatically. The last quarter of the book is very rushed with Mr. Rich describing what should have been key events in less detail than he had used to describe the hero going to a shop early in the game.

Writing Level and Quality

The writing level and vocabulary of Pokémon: Pathways to Adventure is generally appropriate for children under 10. I do not recall having any issues when I read it in 1999. When reading it for this article, I did not note any instances of sentence construction or vocabulary that would not be amenable to the intended audience.

There were two stylistic writing issues that grated on me during my recent reading. Firstly, the book uses way too many exclamation points. It comes off as reminiscent of former presidential candidate Jeb Bush’s infamous “please clap” line from 2016 – as if the book is concerned that readers may lose interest without the dialogue yelling at them. There are also too many instances wherein characters “cried” something. While I appreciate the effort to keep the vocabulary at an age-appropriate level, a broader selection of words to convey that someone said something would have been welcome.

The main technical issue I noted was how the game referred to trainer classes. In Pokémon games, ordinary opposing trainers have classes. Starting with the second Pokémon games (Gold and Silver), opposing trainers had both a name and a class. For example, “Youngster” is a trainer class, but every “Youngster” has a name (e.g., “Youngster Joey”). In the original Pokémon Red and Blue, trainers had only classes and not names. Every Bug Catcher trainer was referred to as Bug Catcher. Every Lass trainer was referred to as Lass. With that being said, it was obvious that these names referred to trainer classes – that is, “Hiker” was not actually a trainer named “Hiker” – it referred to a class of trainers.

At times in Pokémon: Pathways to Adventure, Mr. Rich referred to trainer classes as if they were actual names rather than classes. For example, on page 32, he states that Ash battles a trainer named Lass. Because Lass is a trainer class, rather than a name, Pokémon Red and Blue features many different Lass trainers. Mr. Rich highlighted why precision is important when he wrote on page 33 that Ash again ran into Lass. Again? The Lass depicted on page 33 is a different trainer than the trainer referenced on page 32. A young reader may be left with the wrong impression (and no understanding of what “lass” actually means). The problem persisted – Mr. Rich referred to a trainer named Hiker on page 34 and a trainer named Super Nerd on page 36. Conversely, Mr. Rich described trainers correctly in other parts of the book. For example, a location called Lavender Tower is full of “Channeler” class trainers. On page 65, Mr. Rich referred to Channeler as an actual name of a trainer.

Final Story Assessment

One of the interesting aspects of the original Pokémon games is that they allowe players to create their own stories. Pokémon Red and Blue have a set objective – but with 151 Pokémon and a large amount of freedom in how to use those Pokémon to accomplish the game’s objectives – one can create his or her own story on top of the game’s structure.

I recall enjoying reading Pokémon: Pathways to Adventure back in 1999 when I was a kid. All the while noting its flaws – especially when it came to Mr. Rich’s in-game strategies – I found it interesting to read the story of someone else playing Pokémon. While my classmates had vivid imaginations about the game, Mr. Rich was able to tell the story of a play-through at a much higher level than your average elementary school student.

It was interesting to revisit Pokémon: Pathways to Adventure as an adult reading it with a critical eye. The idea behind the book remains good and interesting. However, its execution was seriously marred by its pacing issues and some oddities in how Mr. Rich opted to navigate the game as a player. I can imagine that many children who read itenjoyed offering their critiques of Mr. Rich’s strategy, much as we questioned Ash’s strange strategic decisions in the Pokémon anime.

Aesthetics

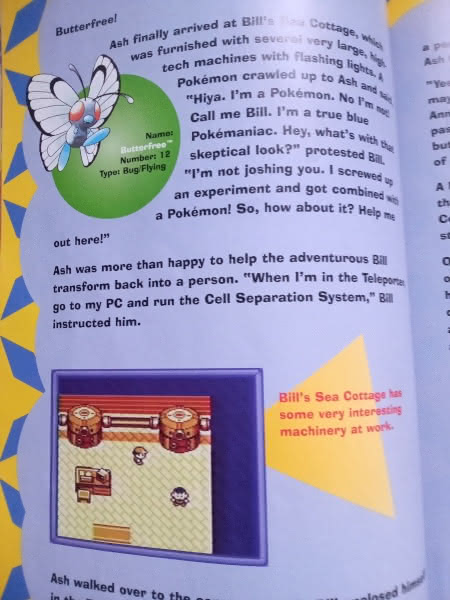

The best thing about Pokémon: Pathways to Adventure today is its aesthetics. The pages are well-printed on non-glossy-magazine-type paper. Interspersed in the pages are a large number of original watercolor illustrations of the first 150 Pokémon by the great Ken Sugimori. Those classic illustrations will take anyone who played Pokémon in the Red/Blue and Gold/Silver days back. The illustrations added a sense of life to the book and were well-placed.

Pokémon: Pathways to Adventure also includes a number of screenshots from the game-play. They are well-printed but in general do not add much value to the book as a guide. The screenshots could have been used more effectively to illustrate key points and concepts.

As a Strategy Guide

Pokémon: Pathways to Adventure was touted not only as a story, but also as a strategy guide. While I noted some ups and downs with respect to how it fared as a story, it was a disaster as a strategy guide. I dare say that Pokémon: Pathways to Adventure aspired to be the Platonic ideal of the specious video game strategy guide that I speciously advocated for in a 2020 article (as opposed to some of the better guides that I remember). I mostly agree with the general consensus of reviewers on Goodreads – but I will explain precisely why it largely failed as a strategy guide below. However, I will begin with some positive points.

The Good

While Pokémon: Pathways to Adventure is not a good strategy guide, it does get some points right. I will note some examples below with page citations:

- Notes the concepts of level, hit points, and attacks (4)

- Makes reference to being able to jump over hedges (9)

- Describes how the mechanics work for switching Pokémon in battle – albeit obfuscates how experience allocation works in the same passage (18-19)

- Distinguishes Technical and Hidden Machines (albeit misses a key point which I note in “Strange Omissions”)

- Includes a useful tip for not wasting time in Lavender Tower and clearing Lavender Tower (53, 66) (but see “To Warn Or Not Warn” for more on 53)

- Notes the importance of depositing unused items (73) and switching Pokémon boxes (82) (but see “Strange Omissions”)

- References the location for capturing Zapdos (84)

These positive points, combined with game screenshots, did give the guide some utility at the time of its publication – notwithstanding its faults and limitations. However, one issue is that young Pokémon players who read at a level sufficient to read Mr. Rich’s book were also at a reading level sufficient to learn all of the above-listed points about Pokémon by simply reading the in-game text. That is, all of the points that I listed above are true, but none were explained by Mr. Rich in a way that would have added much value to a Pokémon player who read well enough to read the book.

Encouraging Error

At the beginning of Pokémon Red and Blue, the player chooses one of three Pokémon to start the game . These Pokémon – Bulbasaur, Squirtle, and Charmander – evolve into fairly strong Pokémon. It is entirely possible to beat Pokémon Red and Blue relying almost exclusively on your starter Pokémon – provided that you actually understand how the game works and know what you are doing. A talented YouTube video producer who goes by JRose11 has a terrific series of videos wherein he beats the entire game exclusively with very weak Pokémon (also recommended in my Blogroll).

However, JRose11 understands Pokémon Red and Blue inside and out and has the benefit of knowing everything about the game’s mechanics – including many points that were not at all understood by your average kid in 1999. He plans his runs in advance – right down to when to teach his Pokémon certain moves in order to maximally preserve his options for overcoming different obstacles.

Thus, while one can beat Pokémon Red and Blue almost exclusively with a starter Pokémon, that is not the best approach for your average 6-10 year old. For one, while the starter Pokémon are reasonably strong, there are stronger Pokémon available in the game. Moreover, like every Pokémon except psychic and normal Pokémon in generation one (due to balancing issues, psychic and normal Pokémon did not really have weaknesses for practical intents and purposes), the three starter Pokémon had strengths and weaknesses. A young player would be well-served putting together a balanced team that could cover different scenarios and eventualities. Many poor six and seven year olds ran into trouble in the final stages of the game because they had relied too much on a single Pokémon and did not have the planning ability or foresight to navigate the Elite Four with that self-imposed limitation. I managed to avoid the starter-exclusive trap, and I still had difficulties with planning when I got to the Elite Four the first time (not the second time a few months later, however).

For whatever reason, Mr. Rich played through Pokémon Red and Blue in the same way that many unfortunate six, seven, and eight-year-olds did and ended up frustrated when it came time to fight the Elite Four. He relied almost exclusively on Charmer the Charmander (eventually Charmer the Charizard) – leveling it to a very high level while generally using the rest of his team as occasional cannon fodder. Mr. Rich managed to power through (albeit not without difficulty – see the long stretch between the first and second gym badges in his book), but he powered through in the precise way that much of his audience got itself in trouble. Mr. Rich’s book would have been a much better resource if it addressed types, team-building, and planning ahead.

Covering Up A Defeat

One of the most interesting sections of Pokémon: Pathways to Adventure is one that is not printed. My friends – I discovered a cover-up.

Charmander and its two evolutions are Fire-type Pokémon. If you are trying to brute force your way through Pokémon Red and Blue with a Charmander (Charmeleon by the time you reach the second Gym), the first two gyms can be complicated since they both feature Pokémon with a type advantage against a fire type Pokemon. The issue is especially pronounced against Misty, the second Gym Leader, whose signature Pokémon, Starmie, not only has a type advantage against Charmleon, but also has high stats and a powerful (for that stage of the game) water attack.

On page 39, “Ash” in Pokémon: Pathways to Adventure beats the preliminary trainers in Misty’s Gym. Mr. Rich then printed Misty’s pre-battle dialogue before saying that Ash had realized he was not ready to fight Misty yet.

Cover-up!

When the player talks to Misty, she offers her pre-battle dialogue before the game transitions into a battle. However, once you decide to talk to Misty – the dye is cast. There is no turning back. It is obvious that the book’s hero initiated a battle against Misty and lost. Given the state of his party and Charmeleon’s level at the time – this is no surprise. In fact, Mr. Rich ultimately then made the correct decision in clearing a different objective before returning to fight Misty at a higher level. But why cover up what would have been the initial loss?

To Warn Or Not Warn?

I wrote a 2020 article encouraging video game strategy guides to lead players to error as a joke – but it raises an interesting question in light of the kind of guide that Pokémon: Pathways to Adventure is.

Here, I will use the case of Lavender Tower. Lavender Tower is a location in Pokémon Red and Blue that is full of ghost-type Pokémon. The original games had a unique mechanic where you could only engage with ghost-type Pokémon (and thus advance through Lavender Tower) if you had a specific key item. The player necessarily encounters Lavender Tower before that item is accessible. The clear intent of Pokémon Red and Blue is that a player would go into Lavender Tower upon first reaching it only to discover that he or she would need to obtain a special item to complete it. However, if you know how the game works in advance, you can easily bypass Lavender Tower when you first encounter it and return only after obtaining the key item.

How do you handle this in the narrative strategy guide? Were I to write the narrative strategy guide, I would play it straight – actually go into Lavender Tower to “learn” that I could not advance. This would be true to how the game was intended to be played in the first instance and more interesting to readers who did not have access to the game (especially since the anime did not feature the same mechanic for ghost Pokémon and Lavender Tower).

Mr. Rich chose a different path. On page 53, he wrote that Ash “read a magazine” that explained that you need an item to see ghosts, so he saved Lavender Tower for later. Fair enough, but at other points, we have no similar convenient foresight.

For example, on page 27, Mr. Rich described Ash’s battle against Brock for the first gym badge in extensive detail. Therein, he described Brock’s Onyx using Brock’s (terrible) signature move, Bide. The way Bide works is that the Pokémon using it does nothing for 2-3 turns before “unleashing energy” – wherein it does 2X the damage it received while using Bide. The easy way to circumvent Brock’s Bide is to not damage Onyx while it is using Bide (at worst, if Onyx is faster and moves first, one can keep the Bide damage to one turn’s worth). Alternatively, if Onyx is on low health or if the player has a water or grass move, one can defeat Onyx before it unleashes energy. Mr. Rich’s Charmander managed to get knocked out by Bide – but the book did not use that as an opportunity to explain how to deal with Bide when choosing Charmander as starter (Bulbasaur and Squirtle both make quick work of Onyx because their same-type moves are X4 effective).

The inconsistency is a bit odd. In one case the book plays as if the player has no idea how Bide works. In another the player takes an optimal path through the game because he does know how the game works.

Biding One’s Time

When the player beats Brock, the first gym leader, the player is awarded a Technical Machine to teach Bide. As I noted above, Bide is a terrible move and no one playing Pokémon Red or Blue should use it outside of some very unusual, specific cases (e.g., JRose11 used it on a solo Eevee run because Eevee has no other way of dealing damage to ghost Pokémon). The reasons why Bide is terrible are twofold. Firstly, it can be circumvented by the other Pokémon simply not attacking. Secondly, there is no guarantee the Pokémon using Bide will be around to unleash energy after taking damage.

But if one must teach Bide to a Pokémon, why in the world would one teach it to his Pikachu – which is one of the most frail Pokémon in the entire game. Against what is Pikachu going to take 2-3 attacks before unleashing energy from Bide? Pikachu does not even have many Hit Points. What would it unleash? Yet for some reason, with no explanation, the hero in Pokémon: Pathways to Adventure teaches Pikachu bide on page 27 – describing it as a “fighting” move. It is technically a Fighting-type move, but it does not function as one.

Hidden Machine Mess

Until recent Pokémon games, players had to use valuable move slots on their Pokémon to get through the game’s overworld. One example that existed in the early games was a move called Cut. Outside of battle, Cut was necessary for clearing certain obstacles. Inside of battle, Cut was a low-power Normal type move that was not a good in-battle choice for anything. Worse yet – in the original Pokémon games, there was no way to unlearn Cut or one of the other moves that had an out-of-battle purpose, and it would take up one of a Pokémon’s four move slots forever. These moves are taught with reuseable items called Hidden Machines.

In light of the fact that Mr. Rich was relying on Charmander/Charmeleon/Charizard almost exclusively, why in the world did he teach it Cut? In Pokémon Red and Blue, the smart thing to do is to keep a utility Pokémon that can learn a number of the special Hidden Machine moves since, with the exception of Surf (and very occasionally, Fly and Strength), the Hidden Machine moves are not useful in battle. Yet, for some incomprehensible reason, Mr. Rich wasted one of his go-to Pokémon’s four precious move slots on a low-power normal-type move that he could have taught to something he was not using. This is not good strategy guide advice.

Strange Omissions

While Mr. Rich was detailed in some areas, he omitted some key points that would have been genuinely useful for young players. I will list some examples below:

- On page 28, Mr. Rich noted that Hidden Machines (HMs) differ from Technical Machines (TMs) in that they can teach a move multiple times instead of once. He neglected to mention that HM moves cannot be unlearned – which is a very important piece of information that a young player may regret not being aware of.

- Mr. Rich did not note the availability of several powerful TMs in the book. He did not, however, mention where to pick up Dig, Body Slam, Ice Beam, Tri Attack, and Blizzard, among others. This was a significant oversight in that several of those moves were easy to miss. Dig and Body Slam would have been very useful for his go-to Pokémon.

- Mr. Rich described Ash buying a Poké Doll in the Celadon City Department Store, but he failed to include what it does.

- Mr. Rich explained how to deposit items (73) and change Pokémon storage boxes (82) – which is good, but he omitted context. Storing items is important because if your inventory becomes full, you cannot pick up new items. Having open slots in your Pokémon storage is important because if your current storage box is full, you cannot catch or acquire new Pokémon until changing boxes. The Pokémon storage boxes can lead to tragic mishaps if one loses track.

- Despite being on a mission to catch all the Pokémon, Mr. Rich did not catch Snorlax (78) and did not explain why.

- Mr. Rich visited the cave where one finds Articuno, but he made no mention of Articuno. I actually missed Articuno (and Zapdos, which Mr. Rich did note) in my very first run – so more could have been said here.

- In other Pokémon omissions, The book does not address the availability of Lapras. It errs in describing Eeevee as “wild” in Celadon City when Eevee is a gift from a non-player character in the Celadon mansion (see page 59).

- The book references the Safari Zone but does not explain the unique way in which Pokémon are caught there.

- The book skips the penultimate battle against the player’s rival between the final gym and the Elite Four. This is worth noting since the rival is at a high level and could be a challenge depending on the player’s circumstances.

There were other omissions that likely stemmed from two factors. Firstly, the second half of the guide was very rushed. Secondly, in light of the fact that Mr. Rich was beating the game almost exclusively with Charmander/Charmeleon/Charizard, many points such as where other Pokemon could acquire powerful moves that Charizard could not learn were not mentioned.

To be clear, I understand that a 100-page book that focuses on turning Pokémon Red and Blue into a story that happens to offer strategies cannot cover everything. However, the omissions I noted above are significant ones that would have been helpful to anyone playing Pokémon – and in some cases cover things that would be easy (or at least possible) to miss without a guide. They merited mentions.

As a Concept

Notwithstanding the limitations of Pokémon: Pathways to Adventure itself, the concept behind it is terrific.

While Pokémon Red and Blue were far from books, they encouraged children to read, think, and reason. They required a basic level of reading proficiency to understand cues in the game’s text dialogues and to read moves, types, and effects.

Pokémon Red and Blue also encouraged kids to imagine. Whereas fancier 3D games (for the time, of course) presented children with a visually dynamic world and a set story, the original Pokémon games were more like a sandbox. The visuals were very simple and the world was small – but between the number of available Pokémon and the different ways of moving through the game, kids could create their own personal stories while playing. The existence of the anime, which offered a full color and full life version of the Pokémon world (albeit not the same universe), gave kids a mental framework to add color to the very visually simple world in the game.

With those points in mind, Pokémon Red and Blue, perhaps more than any game created to that date, were very amenable to being presented in book form. Children, including me, enjoyed reading Pokémon strategy guides. To combine a strategy guide with an adventure book is not only a great idea, but an idea worth exploring and returning to today. Many kids today interact with the internet in ways that reduce their ability to attend to books and text-heavy games. Finding ways to build reading into games (see Pokémon itself) and games into reading (see this book) has potential for encouraging kids to read and develop healthy content consumption habits. Moreover, there are many creative independent game designers who could consider ways to combine games and reading to make interesting products for all ages.

Conclusion

Despite its flaws, it was fun re-visiting Pokémon: Pathways to Adventure more than two decades after I read it as a kid. I was almost surprised to discover how many details I remembered upon seeing them – for example, the strange omission of Ash’s loss to Misty (I did catch that as a kid), not to mention the ubiquitous Charmer the Charizard. I also love seeing good prints of the original Pokémon designs – we need more of those aesthetic watercolor illustrations. While this particular book did not accomplish all of its goals, it was still a fun read – and, as I noted above, I think that it provides some interesting ideas for game designers and educators to consider today (perhaps without the time constraints that haunted this particular effort).