Issue 2 of Volume XXXIII (33) of The American Bee Journal was published on January 11, 1894. What was The American Bee Journal? It touted itself as the “Oldest Bee-Paper In America” and as being “Devoted Exclusive—To Bee-Culture.” I suppose that we can say it came exactly as advertised. What shall we concern ourselves with from The American Bee Journal? A quaint matter, I assure you. We will study the issue’s biography of Mr. Franklin Wilcox, a prominent bee-keeper of his day, and his work at the 1893 World’s Fair.

Why are we doing this? Well firstly, I like to dig up unusual content from old magazines and journals for publication at The New Leaf Journal. Secondly, this will launch a new subsection of The New Leaf Journal – The Emu Bee.

Introducing a Wisconsin Bee-Keeper, Franklin Wilcox

The American Bee Journal met Mr. Franklin Wilcox at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. It described him as “[o]ne of the prominent figures on the wonderful gallery of the Agricultural Building at the recent World’s Fair.” The Journal stated that,while they had never met Mr. Wilcox before the World’s Fair, but wrote that “as in many other nice bee-folks whom we first met the past year, we have indeed a good and true friend.” (Quoted verbatim.) You can see the magazine’s picture of the esteemed bee-keeper below.

The American Bee Journal decided to write a profile of Mr. Wilcox for its first issue in 1894.

The Wisconsin Bee-Keeper From Ohio

Mr. Wilcox lived in Mauston, Wisconsin. He was born in Hardin County, Ohio, in 1840, making him 53 or 54 at the time of the Bee Journal’s profile. He moved to Juneau County, Wisconsin, in 1851, “near where he now resides.”

It was in Wisconsin that Mr. Wilcox first encountered bee-keeping. The journal explained:

There being no school to occupy his mind, for a few years he spent much of his time in the summer season hunting his father’s cows—for pastures were bounded only by the horizon, and the cows seemed anxious to find the outer edge; in the fall he frequently went with his father bee-hunting, and there learned from observation some practical lessons in bee-keeping, and we think he would spend a little time each fall yet, in the woods, “lining up” the wild bees, if time would permit.

The American Bee Journal on Mr. Franklin Wilcox

Franklin Wilcox at War

Like millions of other young men his age, Mr. Wilcox joined the Union Army in the Civil War. The American Bee Journal stated that he was in the Army for the duration of the war, but he was disabled from active service for one year after being wounded at the Battle of South Mountain in Maryland, in September 1862.

Mr. Wilcox wed at the closing of hostilities and settled on the Wisconsin farm where he still lived in 1894. “He thinks himself quite content with his comfortable home, a good wife, and four children.”

Franklin Wilcox as Bee-Keeper

The American Bee Journal wrote that Mr. Wilcox kept a few colonies of bees until about 1877 or 1878. About that time, “he subscribed for the American Bee Journal, and soon after added Gleanings, ‘Cook’s Manual,’ and several other bee-works.” These bee magazines set Mr. Wilcox down a new path. We are told that “[a]fter a few months’ reading, he chose a hive, and commenced bee-keeping in a new way, that astonished his parents and some of his neighbors.”

By 1894, Mr. Wilcox was a prolific bee-keepers. “He now commences each season with from 200 to 300 colonies of bees, and realizes as much profit from them as any farmer with the same amount of capital and labor.”

In addition to his bee-keeping, “Mr. Wilcox has been the Secretary of a farmer’s mutual insurance company for the past 15 years, which does business in four towns only, and carries a capital stock of $500,000.” According to inflation calculators, that would be just over $15 million in today’s money.

Franklin Wilcox’s Bee Exhibit at the 1893 World’s Fair

The issue of The American Bee Journal described the exhibit that Mr. Wilcox was responsible for at the 1893 World’s Fair. “At the annual meeting of the Wisconsin State Bee-Keepers’ Association, in February, 1893, Mr. Franklin Wilcox, of Mauston, Wis., was chosen to collect, prepare and arrange an exhibit of honey and wax at the World’s Columbian Exposition.” “World’s Columbian Exposition” refers to the World’s Fair that year. The Journal notes that Mr. Wilcox received $500 from the state board to put together the exhibit, just over $14,000 in today’s money.

Challenges Collecting Honey and Beeswax

Mr. Wilcox ran into difficulty because “February and March [of 1893] did not prove to be the most favorable time for collecting comb honey that should fairly represent the State.” At least it was not October. However, Mr. Wilcox traveled the state and “succeeded in obtaining about 800 pounds of comb honey, 500 pounds of extracted, and 200 pounds of beeswax, of the crop of 1892.” The article further notes that “[d]amages from freezing and rough handling reduced the quantity somewhat before it was finally installed in Chicago.”

Mr. Wilcox also had budgetary concerns. He was working under rules that limited each exhibitor in the exhibition “to 50 pounds of extracted, and 100 pounds of comb honey…” It adds that it would have been more cost-efficient if the exhibit could have been filled “with a large quantity of fancy honey from two or three exhibitors…”

The article listed several Wisconsin bee-keepers who contributed from their 1892 crop to the exhibition:

- Mr. J.J. Ochsner of Prairie du Sac (“sent some of the finest comb and extracted honey, and some choice beeswax; but the most attractive exhibit by Mr. O was his name and post-office address built of comb honey by the bees in letters formed for them as a guide”)

- Mr. C.A. Hatch of Ithica (extracted honey and beeswax)

- Mr. E.C. Priest of Henrietta (extracted honey and beeswax)

- Mr. Frank McNay of Mauston (comb and extracted honey and beeswax)

- Mr. A.E. Wilcox of Mauston (comb and extracted honey and beeswax)

- Mr. Adolph Vandereicke

Finally, Mr. Franklin Wilcox himself submitted comb and extracted honey and beeswax. The article does not note whether Mr. A.E. Wilcox of Mauston was related to Franklin Wilcox, but it seems like a fair inference to suggest that he was.

Procuring the 1893 Crop

Mr. Wilcox had the extracted honey put in glass jars “designed to show those commonly used in the retail trade.” The Journal added that “[It] nearly all appeared on exhibition in granulated form,” in part “because Mr. Wilcox believed that people should learn to know that pure extracted honey will granulate, and partly because he could not give it time enough to melt it so often as necessary to keep it in liquid form.”

After Mr. Wilcox created the exhibition with the crop of 1892, he asked the Wisconsin State Board for funds to replace the 1892 crop with the 1893 crop, when the crop would be ready. He was refused, but undeterred, he left the exhibit to find fresh honey in August after finding that other states had improved their exhibits. The Wisconsin Board reversed course, and promised $100 to Mr. Wilcox to pay for transporting and installing the fresh honey.

Mr. Wilcox’s call for immediate contributions of honey was answered. J.W. Kleeber of Reedsburg contributed 50 pounds of honey, and J.J. Ochsner, who had previously contributed from his 1892 crop, contributed 300 pounds and an additional 200 pounds from himself and his son.

All’s Well That Ends Well

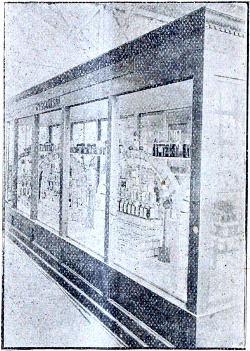

This was arranged on five large arches, as shown in the illustration herewith, with pyramids of honey underneath. Those columns with a square base and two balls on top are beeswax. The remainder of the [beeswax] was is in fancy balls, bells, hearts, etc., and may be seen on top of the sections, glass and jars of honey.

The American Bee Journal on Wisconsin’s Bee-Keeping exhibition at the 1893 World’s Fair

It noted that the previously described name and post office address of Mr. Ochsner, made of comb honey, are in the above picture, albeit hard to see.

The Wisconsin exhibit was much-loved, winning awards along with Michigan “mainly due to the untiring efforts and wisdom of one man,” Mr. Franklin Wilcox. The Journal opined that Mr. Wilcox “worked faithfully and hard in securing and placing [his] exhibit,” and that he “won lasting honor, if not financial reward,” for his efforts. The Journal concluded that it was unlikely that Wisconsin bee-keepers “will soon forget the [man] who did so much to win new laurels” for the Wisconsin bee-keeping industry.

Concluding Bee Thoughts

Old magazines and journals like this edition of The American Bee Journal are full of stories and anecdotes about interesting people who are otherwise mostly lost to history. Mr. Franklin Wilcox was a prominent man within Wisconsin bee-keeping and farming circles. He was called upon by his trade organization to take the lead in organizing Wisconsin’s bee-keeping exhibition at the World’s Fair. It sounds like he had a difficult job from the short description, but he was ultimately successful and “won lasting honor” for his efforts.

Mr. Wilcox apparently took up bee-keeping in earnest after reading about it in The American Bee Journal and several other prominent bee-publications of the day. He served his country before successfully serving his State at the World’s Fair. We cannot give him much for his efforts and a life well lived other than lasting honor in the pages of The New Leaf Journal.