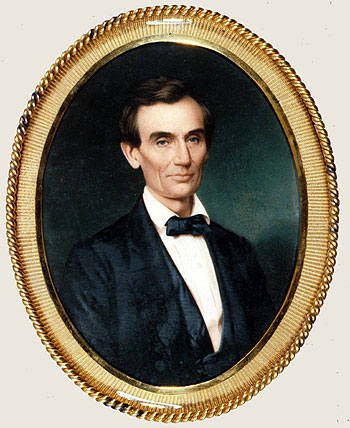

The March 1896 issue of McClure’s Magazine includes the backstory of an interesting 1860 ambrotype of Abraham Lincoln. The ambrotype itself was taken in Springfield, Illinois, on August 13, 1860 – less than three months after Lincoln had accepted the Republican nomination for president. Lincoln presented this ambrotype to J. Henry Brown, an artist who then completed a miniature painting of Lincoln in late August 1860 to commemorate his nomination.

Below, we will examine the story behind an 1860 Lincoln ambrotype and John Henry Brown’s watercolor-on-ivory miniature painting of Lincoln.

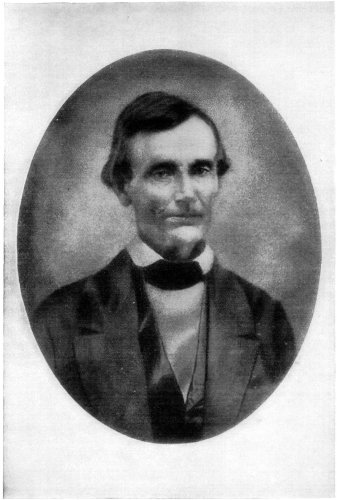

August 1860 Lincoln Ambrotype

Below, you will find the August 13, 1860, ambrotype of Lincoln, as it appeared in McClure’s:

According to McClure’s Magazine, its publication of the photo in 1896 was the first publication of the photo.

At the time of publication, the Lincoln ambrotype was owned by William H, Lambert, a gentleman from Philadelphia, who allowed the magazine to reproduce it.

For his part, Lambert had purchased the ambrotype from W.P. Brown of Philadelphia. W.P Brown wrote of the portrait:

This picture, along with another one of the same kind, was presented by President Lincoln to my father, J. Henry Brown, deceased (miniature artist), after he had finished painting Lincoln’s picture on ivory, at Springfield, Illinois. The commission was given my father by Judge Read (John M. Read of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania), immediately after Lincoln’s nomination for the Presidency. One of the ambrotypes I sold to the Historical Society of Boston, Massachusetts, and it is now in their possession.

John Henry Brown’s August 1860 Miniature Painting of Lincoln

McClure’s does not reprint the second Lincoln ambrotype that had been owned by John Henry Brown, but it does offer more information about Brown’s miniature painting.

Brown’s painting was engraved by a Samuel Sartain and circulated between Lincoln’s winning the 1860 election and his inauguration. You can view the miniature painting below, courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution:

McClure’s notes that Lincoln grew a beard not too long after Brown’s miniature was completed. Sartain, being a talented craftsman, adapted to this change in circumstances by adding a beard to his engraving plate. The engraving continued to sell well.

As of 1896, the original J. Henry Brown miniature painting of Abraham Lincoln was owned by Lincoln’s son, Robert Todd Lincoln.

John Henry Brown’s Journal

John Henry Brown died some time before 1896. He left behind a manuscript journal which contained, among many other things, several entries detailing his process of painting the miniature portrait of Abraham Lincoln. McClure’s reprinted the journal entries, spanning from August 12, 1860, to August 27, 1860, in their entirety. We shall do the same below, separating the entries into several sections in order to enhance readability.

August 12, 1860

The August 12, 1860, entry details Brown’s arriving in Springfield, Illinois. Brown wrote: “Sunday. Arrived here at three o’clock in the morning. Wrote some letters.”

August 13, 1860

Brown contacted Lincoln and presented him with his assignment.

Called at Mr. Lincoln’s house to see him. As he was not in, I was directed to the Executive Chamber, in the State Capitol. I found him there. Handed him my letters from Judge Read. He at once consented to sit for his picture. We walked together from the Executive Chamber to a daguerrean establishment. I had a half dozen of ambrotypes taken of him before I could get one to suit me. I was at once most favorably impressed with Mr. Lincoln. In the afternoon I unpacked my painting materials.

You may refer to the first image in the article for one of the August 13 ambrotypes of Lincoln.

August 14-25, 1860

The following entries feature Brown’s notes and comments about completing his miniature painting of Lincoln.

- 8/14: “Commenced Mr. Lincoln’s picture; at it all day.”

- 8/15: “At Mr. Lincoln’s picture.”

- 8/16: “Mr. Lincoln gave me his first sitting, in the library room of the State Capitol. Called to see Mrs. Lincoln; much pleased with her. Wrote five letters.”

- 8/17, 18: “At Mr. Lincoln’s picture. Received an invitation from Mrs. Lincoln to take tea with them.”

- 8/19: “Sunday. Wrote letters.”

- 8/20: “Mr. Lincoln’s second sitting. Have arranged to have his sittings in the Representative Chamber.”

- 8/21: “At Mr. Lincoln’s picture. Heard from home; all well. ”

- 8/22: “Mr. Lincoln’s third sitting. ”

- 8/23: “At Mr. Lincoln’s picture. ”

- 8/24: “Mr. Lincoln’s fourth sitting.

- 8/25: “Lincoln’s fifth and last sitting. The picture gives great satisfaction; Mrs. Lincoln speaks of it in the most extravagant forms of approbation. ”

August 26, 1860

Brown completed his portrait of Lincoln on Saturday, August 25, and went to church on the morning of Sunday, August 26. There, he saw Lincoln, who was also in attendance. Perhaps with some time to breathe, he offered his positive appraisals of Abraham and Mary Todd Lincoln.

Sunday. At church. Saw Mr. Lincoln there. I hardly know how to express the strength of my personal regard for Mr. Lincoln. I never saw a man for whom I so soon formed an attachment. I like him much, and agree with him in all things but his politics. He is kind and very sociable; immensely popular among the people of Springfield; even those opposed to him in politics speak of him in unqualified terms of praise. He is fifty-one years old, six feet four inches high, and weighs one hundred and sixty pounds. There are so many hard lines in his face that it becomes a mask to the inner man. His true character only shines out when in an animated conversation, or when telling an amusing tale, of which he is very fond. He is said to be a homely man; I do not think so. Mrs. Lincoln is a very fine-looking woman, apparently in excellent health, and seems to be about forty or forty-five years of age.

This entry contains many nice touches that squarely place Brown’s entry at the time when it was written. Lincoln was not yet an iconic figure, but merely a prominent politician and, at that moment, potential next president. Brown speaks glowingly of Lincoln the man, while noting, interestingly, that he agreed with him “in all things but his politics.”

August 27, 1860

This is the final entry of Brown’s journal that was reprinted by McClure’s.

The people of Springfield who have seen Mr. Lincoln’s picture speak of it in strong terms of approbation, declaring it to be the best that has yet been taken of him. Received a letter from Mr. Lincoln indorsing the picture; also one from Mrs. Lincoln expressing her unqualified satisfaction with it; also one from Mr. John G. Nicolay, Mr. Lincoln’s confidential clerk; and one from the man who took the ambrotype. This would be, I suppose, the proper place to say a word about Springfield, the prairie city, as it is sometimes called. It is a very pretty place; the streets eighty feet wide. It contains many very fine buildings, and has a population of about ten thousand.

Final Thoughts and a Bonus Ambrotype

With that final entry, Brown moved on to whatever his next assignment was. Lincoln went on as well, and he would be inaugurated as the 16th President of the United States just short of 7 months after Brown completed his miniature. The most well-known photographs and paintings of Lincoln during his presidency come from 1861-1865. Despite the fact that very little time had passed since Lincoln sat for Brown on five occasions, the man in those presidential photographs appears a great deal older.

The 1860 ambrotypes and the miniature painting captured Lincoln the man, before he became the Lincoln of legend, at a particular time and place. Brown’s journal entries captured the sentiments of a painter at that specific time and place, when he likely had little idea how interesting his story would be to posterity.