Back in May, I published an article on the subject of video game visuals that age well. In that post, I observed that as technology improves over time the games considered the most visually impressive in the moment on a technical level may not age as well as games that focus more on aesthetics than raw power. I noted that, with perfect hindsight, the most aesthetic well-known console game of the 1990s may well be Super Mario World 2: Yoshi’s Island, a game that won accolades for its visual style when it was released in 1995 but that did not awe audiences in the same way that the fully 3D Super Mario 64 did in 1996. I posed a question with respect to game development with an eye toward the future based on my survey:

[D]oes [a] game aspire to be a game of the hour or a game for all time? A game of the hour need only produce technically impressive visuals with respect to the current state of hardware. A game for all time must have genuinely pretty and aesthetic visuals that will continue to impress stylistically even after the current generation of hardware is obsolete.

That post focused only on game visuals. However, taking a broader view, I do not think that visuals, aesthetic or otherwise, are what is most likely to give rise to a game that ages well over the decades. That Super Mario World 2: Yoshi’s Island is beautiful would not support its enduring esteem without excellent game-play. But rather than address platforming games here, I want to consider story-centric games. A game with a heavy focus on narrative and story has unique potential to age gracefully so long as it is fundamentally fun to play. While other aspects may not age as well, a good story with a strong message is timeless.

I came across a very interesting 1993 interview with Mr. Hitoshi Yasuda, the scenario writer for an old RPG titled Laplace no Ma. The interview was translated and re-published by shumplations. The world of games was in an interesting place in 1993. The most successful console in the world was the Super Nintendo Entertainment System, and it was challenged primarily by the Sega Genesis in the United States and by the Turbografix 16 in Japan. However, a couple of next-generation consoles focusing primarily on 3D games were already in development, and 1994 would see the release of the first successful consoles of the revolutionary next generation, the Sony PlayStation and Sega Saturn. Thus, while the epicenter of the gaming industry was still set in the 2D era in 1993, impending change was on the horizon.

It is with this in mind that I turn to Mr. Yasuda’s interview. Mr. Yasuda was a scenario writer, which unsurprisingly led to his main interest in games being stories and structure. Mr. Yasuda was quite blunt in his interview, honestly listing things that he liked and did not like about the overall state of role-playing games in 1993. He provided an interesting answer to the question of what game developers needed to do to produce better role-playing games going forward:

Right now new hardware is coming out so fast, there’s no time to catch your breath. The consequence of that is developers focus on eye-catching visuals and sound, only trying to awe users. They’re selling cheap thrills, in other words. What I’d like to see in the future, is developers also value the thrill of a good story or battle system… that’d be nice, right?

Mr. Yasuda did not expressly reference posterity in his assessment. However, his quote ties in well to my article on video game visuals that age well while expanding the point to additional, more important areas. The concept of “eye-catching visuals” is usually relative, absent situations where the speaker is referring to aesthetics instead of realism or power. A game that pushed the limits of technology in 1993 or 1994 was unlikely to look particularly impressive by the late 90s, and insofar as realism went, the Sega Dreamcast obsoleted every console that came before it from the moment of its launch in 1999. That is, a game that relied on the sort of “cheap thrills” that Mr. Yasuda referred to with derision was unlikely to have a long shelf life. Conversely, a game that focuses on “the thrill of a good story or battle system” is not only likely to provide a richer experience in the moment, but also to be fun in the future, well after new technology renders the “cheap thrills” of the past “cheap” without the “thrill.”

Mr. Yasuda’s quote caused me to consider whether in the context of a role-playing game the story or the battle system is more important to the game’s aging well. To some extent, both are important. A good story can be marred by tedious game-play. Mr. Yasuda commented on this phenomenon:

I think battles themselves are very fun. However, if the encounter rate is too high, players get sick of it. This also weighs down the pacing of the story.

However, a long role-playing game with little in the way of story relies heavily on its game-play and battle system. This too can be an issue with respect to how well the game ages. Over time, the best developers (ideally) learn from earlier games and implement new battle systems and quality of life improvements to make long role-playing games more enjoyable.

For role-playing games with a story-focus, both the story and battle-system are important to a point. A good story will not save a game that is not fun, and a mediocre story next to a decent battle system may not age well compared to later games. But when forced to choose, I think that assuming the existence of a decent system, the story is more central to a role-playing game aging well. I will use the last three entries of the popular Persona series, Persona 3, Persona 4, and Persona 5 as an example (see my Persona 4 articles). I think that all three are still fun to play. The Persona series follows my above observation about battle systems. Persona 3’s battle system, as well as other systems, feels primitive compared to Persona 4. Persona 5 introduced significant improvements to the battle-system and other battle-related elements over Persona 4. But in this editor’s opinion, Persona 4, which has the best character writing of the series, is the best game of the trio, notwithstanding the technical and game-play improvements introduced in Persona 5. Persona 3 has the best atmosphere and a good overarching story, but even if I thought that it had the strongest writing and story, its battle system and other system-related limitations would likely hold me back from concluding that it aged better than its predecessors or successors.

I conclude with another New Leaf Journal tie-in inspired by Mr. Yasuda’s interview. The scenario-writer offered a suggestion for what he would like to see in more role-playing games:

I’d also like to see multi-scenario games, and multiple endings. I think Romancing Saga is very well-done. It’s a relatively new experiment, so players approach it not knowing how to play. The problem is when things become hackneyed and fixed.

My New Leaf Journal colleague, Victor V. Gurbo, expressed the same desire for games with branching paths, multiple endings, and open worlds in a 2020 post (see my response). With the benefit of hindsight, I think that the most ambitious multiple-ending efforts have been visual novels rather than traditional video games and role-playing games. However, many role-playing games and open world games allow the player to forge his or her own path to a defined conclusion.

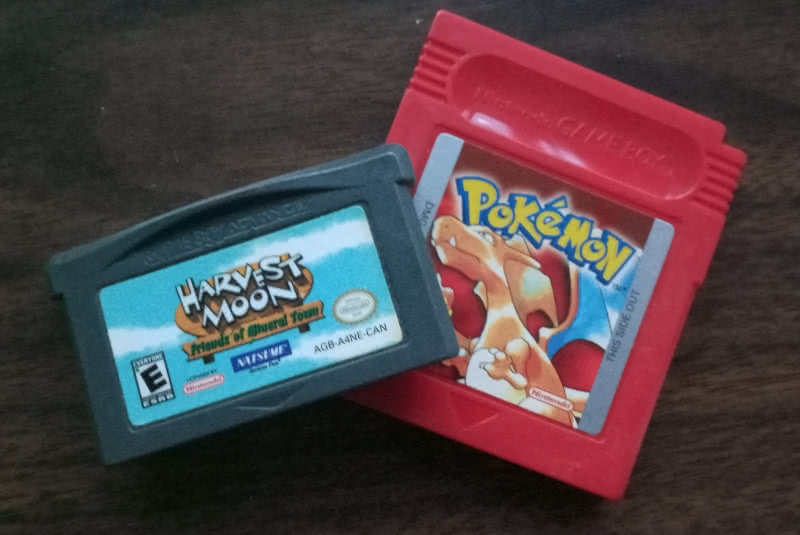

The Persona series is one such example in that the player has a good amount of freedom to spend his or her time in certain ways and get to know different characters. The most popular role-playing game series of all time, Pokémon, is another example of encouraging players to chart their own courses to a defined conclusion. I share Mr. Yasuda’s desire for more role-playing games with genuinely branching paths and narratives (another one of my favorite modern games, Fire Emblem: Three Houses, provides a decent example), but I think that role playing games that meet the minimum threshold of giving the player room to fill the pages of a story between the beginning and the ending are conducive to aging well, even if the ending is ultimately fixed.