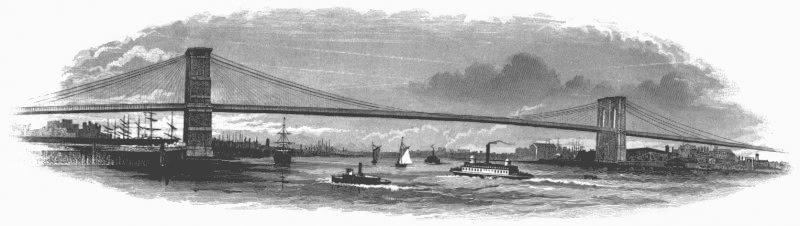

New York City’s iconic Brooklyn Bridge was officially opened to the public on May 24, 1883, after 13 years of construction. The opening was greeted by dignitaries (foreign and domestic), copious speech-making, and general merriment. Being from the area, and having featured contemporary photographs of the Brooklyn Bridge in these pages, I decided to put together a post containing original accounts of the festivities of May 24, 1883.

Before I begin, note that this post will cover the festivities – but not the orations delivered at the Brooklyn Bridge opening ceremony. I will reserve discussion of the speeches for a future post.

Note on footnotes

You can find all of my sources in the footnotes section of this article – all quotations from sources are assigned with a number matching the source footnote. See footnotes.

Preview of the festivities

The May 24, 1883 edition of The Sun, a New York-based newspaper, previewed the events that were to accompany the opening of the Brooklyn Bridge. First, it looked back on the Bridge’s origins:

On the 3d of January, 1870, the work of preparing for the foundation of the tower in Brooklyn was begun; and the stone tablet close to the top of that mighty pile bears the date of 1875. A similar tablet in the face of the New York pier bears the same date, although it was not finished and ready for the cable until a year later.[1]

In 1883, there was not yet a unified “New York City” consisting of five boroughs (consolidation occurred in 1898). Brooklyn and Manhattan were still distinct cities, each having its own mayor. The Sun highlights this point in other passages discussing the significance of the Brooklyn Bridge. For example, The Sun predicted that “[t]he bridge will doubtless be of great convenience to the inhabitants of both cities,” referring to Manhattan and Brooklyn.[1]

(Perhaps New York City’s five boroughs should have remained separate cities. Were New York City to be broken up, Brooklyn would be the 3rd largest city in the United States by population as of the 2020 Census (within 10,000 residents of Chicago, which would sit in second place), Queens would be fourth largest, and Manhattan would be sixth largest. But I digress.)

The Sun continued:

[T]o-day, a little more than thirteen years from the time of the beginning, Mayor Low will enter the bridge from the Brooklyn end with a crowd of his fellow citizens, and wait at the Brooklyn Station to receive the Mayor of New York, who will come across with a crowd of his fellow citizens, including the President of the United States.[1]

Seth Low was the Mayor of Brooklyn on May 24, 1883. By Mayor of New York, The Sun was referring to the mayor of an area which then consisted of Manhattan and part of what is now the Bronx. The Mayor of New York at that time was Franklin Edson. The President of the United States as of May 24, 1883, was New York’s own Chester Alan Arthur. The Sun, I gather, was not a fan of the President:

The distinguished party will be wise if they walk across on the raised footway in the centre. They should not walk very fast, for the grade is too steep for the ponderous form of President Arthur to be hurried much beyond the meditative step of a fisherman, if he is to arrive at the Brooklyn side with proper dignity.[1]

Setting aside The Sun’s colorful potshot at President Arthur’s weight and physical conditioning (but granting that “meditative step of the fisherman” and the use of “proper dignity” are much better shot-taking than what you see in newspapers these days), The Sun was correct to note “the grade” of the Bridge. The Brooklyn Bridge features a climb at the start of both its Brooklyn and Manhattan sides (necessarily turning into a descent at the respective far ends). It is comparatively flat in its center span over the East River.

The Sun imagined a conversation between New York’s Mayor Edson and President Arthur, with Edson pointing out sights from the bridge to Arthur. I have some doubts that Edson would have deemed it necessary to teach Arthur, a long-time resident of Manhattan and power-player in New York politics, about the sights in Manhattan. But The Sun quickly showed that its objective was in this passage was to set up another punch-line at the President’s expense instead of predicting what would transpire:

[Mayor Edson] can point out the tall tower of the Tribune, whose roof is higher than the President can get on the bridge, unless he should ascend to the top of one of the piers. Gen. Arthur must not forget, however, that near to the Tribune is the unpretentious office of THE SUN, which has the same disposition to do justice to him as to every other man. About the only novel object that the President can call the Mayor’s attention to, will be a handsome steam yacht which was built for his own use by Mr. HENRY N. SMITH of Wall Street, the owner of Goldsmith Maid.[1]

Recounting the festivities

The Sun’s article was published in the morning edition of the paper, meaning that it was looking ahead to the Brooklyn Bridge opening ceremony instead of looking back at what had occurred. The official retrospective on what occurred on March 24, 1883, was published in Opening Ceremonies of the New York and Brooklyn Bridge, which was printed by the The Brooklyn Eagle Job Printing Department (the original printing building still exists on Old Fulton Street in DUMBO). It is available on Project Gutenberg in many formats (I will refer to it as The Eagle for simplicity).[2] The volume re-printed the orations delivered at the Brooklyn Bridge ceremony. While we will cover those in brief, we are most interested here in the Eagle’s description of the events of May 24, 1883. I will supplement the Eagle’s account by directing you to a very detailed account in the May 24, 1883 edition of Washington DC’s Evening Star (the report is described as a telegram report, but I will refer to it as The Evening Star’s report for the sake of simplicity).[3] The Evening Star report appears to have been completed after the festivities had begun but before the speeches for the Bridge ceremony were delivered in Brooklyn in the afternoon.

The Eagle’s account began: “The New York and Brooklyn Bridge was formally opened on Thursday, May 24, 1883, with befitting pomp and ceremonial, in the presence of the largest multitude that ever gathered in the two cities.”[2] According to The Eagle, “it was evidence that the popular demonstration would be upon a scale commensurate with the magnificence of the structure and its importance to the people of the United States.”[2] The Evening Star reported after the fact that the occasion lived up to the lofty expectations:

To-day was a gala day in Brooklyn. Throughout the city there appeared to be a general surrender of business to sight-seeing and celebration one way or another. The main business avenues, the heights and many of the streets clear out into the suburbs are decked most gailly with flags and bunting, and dowers for the bridal with the city over the river. Public buildings, private houses, street cars, wagons and trucks fly the colors of all nations in honor of the opening of the big bridge.[3]

The Eagle noted that the commemorations of the opening of the Brooklyn Bridge “were not confined to the metropolis and its sister city on the Long Island shore, nor yet to the majestic Empire State.”[2] The Los Angeles Herald evinced the national regard in which the Brooklyn Bridge was held in a May 25, 1883 report:[4]

The eighth wonder of the world–eighth in point of time, but first in point of significance, was to-day dedicated to the use of the people amid the booming of canon, the shrill whistling of a thousand steamers, and the plaudits of great masses of citizens, the Brooklyn bridge was formally presented to the citizens of New York and Brooklyn.

But while the opening of the Brooklyn Bridge was a nationally recognized event, the heart of the festivities was in Brooklyn, New York. The Eagle:

In the communities most directly benefited by the Bridge the demonstration was confined to no class or body of the populace. It was a holiday for high and low, rich and poor; it was, in fact, the People’s Day. More delightful weather never dawned upon a festal morning. The heavens were radiant with the celestial blue of approaching summer; silvery fragments of cloud sailed gracefully across the firmament like winged messengers, bearing greetings of work well done; the clearest of spring sunshine tinged everything with a touch of gold, and a brisk, bracing breeze blown up from the Atlantic cooled the atmosphere to a healthful and invigorating temperature. The incoming dawn revealed the twin cities gorgeous in gala attire. From towering steeple and lofty façade, from the fronts of business houses and the cornices and walls of private dwellings, from the forests of shipping along the wharves and the vessels in the dimpled bay, floated bunting fashioned in every conceivable design, while high above all, from the massive and enduring granite towers of the Bridge the Stars and Stripes signaled to the world from the gateway of the continent the arrival of the auspicious day.[2]

The Eagle reported on events in a down-to-Earth way as well. It noted that the festival mood had taken over “both cities,” here being Manhattan and Brooklyn, “[a]lmost before the sun was up.”[2] The New York Times reported one day after the opening ceremony that while the festivities spanned Brooklyn and Manhattan, it was a decidedly Brooklyn-centric affair:

“The pleasant weather brought visitors by the thousands from all around. … It is estimated that over 50,000 people came in by the railroads alone, and swarms by the sound boats and by the ferry-boats helped to swell the crowds in both cities. … The opening of the bridge was decidedly Brooklyn’s celebration. New York’s participation in it was meager, save as to the crowd which thronged her streets.”[5]

Business, according to The Eagle, “was generally suspended.”[2] The Evening Star offered more detail, first regarding Brooklyn:

To-day was a gala day in Brooklyn. Throughout the city there appeared to be a general surrender of business to sight-seeing and celebration one way or another.[3]

Note again that in the above passage, “city” refers to Brooklyn. The Evening Star reported separately on the state of business in Manhattan:

In New York also business was partly suspended to-day. Most of the down town exchanges closed at noon, and many business places suspended work for the afternoon.

While business were either closed for the full day or part of the day, “[t]he mercantile professional communities vied with one another in the extent and splendor of their decorations, while from the hearty voice of Labor arose a chorus of ringing acclamation.”[2] While regular business was closed, special business commemorating the occasion flourished:

The vendors of bridge souvenirs were about in hundreds, and found a ready sale for their wears. Enterprising merchants took this opportunity of advertising their wares on the backs of pictures of the Brooklyn Bridge.[3]

The Eagle reported:

Tens of thousands of men, women and children crowded into the streets, and, after gazing admiringly upon the decorations, wended their way in the direction of the mighty river span. From neighboring cities and from the adjacent county for many miles around the incoming trains brought multitudes of excursionists and sight-seers.”[2]

What sorts of the decorations and embellishments did these thousands of people see? I turn to The Evening Star for a detailed explanation, beginning with Brooklyn:

Fulton street, from its furthest end to the river front, is gay with colors. The decoration of the Academy of Music occupies the attention of a small army of men, and is being prepared for the reception tonight.[3]

“Fulton Street” today begins in downtown Brooklyn (just above Brooklyn Borough Hall) and runs for a long way, all the way into Queens. It once began from Fulton Ferry Landing in what is now DUMBO, which terminates at the foot of the new Brooklyn Bridge Park. There is now an Old Fulton Street running for a few blocks in DUMBO, disconnected from the rest of Fulton after many changes over the decades. Wikipedia has a good write-up on the different stages of Fulton.

The Evening Star continued:

All through Columbia Heights, and the streets opening into that fashionable neighborhood decoration was general, and the effect handsome.[3]

Columbia Heights here refers to what is now Brooklyn Heights. Brooklyn Heights has a street called Columbia Heights which runs adjacent to the Brooklyn Heights Promenade.

Columbia Heights, now Brooklyn Heights, housed two individuals significant to the occasion:

The houses of Col. Roebling, the chief engineer of the bridge, and that of Mayor Low, of Brooklyn, are decorated with flowers and bunting and the coat of arms of New York and Brooklyn.[3]

Sadly, Washington Augustus Roebling, the chief engineer, was unable to attend the ceremony due to poor health (note, however, that he lived until 1926):

The invalid engineer will receive the President and mayor, and in the evening for a brief hour the public. Col. Roebling is feeling better to-day but is too weak to leave his house and share in the ceremonies of the bridge.[3]

While Washington Roebling did not attend the opening ceremony, his wife, Emily Roebling, attended in his stead.[5] The “President” in the above passage refers to then-President of the United States, Chester A. Arthur, who as we learned in The Sun report was transiting the Bridge from Manhattan to attend the ceremony in Brooklyn.

The Evening Star detailed the festive scene in Manhattan, referred to as “New York” in its reportage:

Flags flew from the municipal and other buildings in the City Hall Park, from business houses along Broadway and other streets and from many private residences.[3]

City Hall Park sits right at the foot of the Manhattan pedestrian entrance to the Brooklyn Bridge, and City Hall is highly visible from the Bridge’s walkway when walking toward Manhattan. In contrast, Brooklyn’s Borough Hall is only a short walk to and from the Bridge’s pedestrian entrances on the Brooklyn side (about 5-10 minutes), but there is no view of the building from the Bridge or from Manhattan.

The Evening Star continued about the scene in Manhattan:

The houses along the route of the procession from the Fifth-avenue hotel to the city hall were decked with colors. At the New York end of the bridge workmen had been busy all the morning putting the finishing touches to the decorations.[3]

The Eagle wrote that “[t]he scenes presented during the day upon the streets and avenues of New York and Brooklyn will never be forgotten by those who witnessed them.”[2] The foregoing descriptions suggest that this is not hyperbole.

Our accounts are in accord in reporting that order was maintained. “Notwithstanding the enormous massing of people, the best of order was everywhere observable, and the day happily was free from any accident of a serious nature.”[2] From The Evening Star on the Manhattan side of the bridge:

The picket fence in front of the bridge had been removed and a strong force of police guarded its approach. Crowds of people began to gather early and awaited with great patience the arrival of the procession and the beginning of the ceremonies. All vehicles except street cars were prevented from passing below the streets near the bridge from an early hour in the morning, and at noon the street cars were stopped.[3]

The procession from Manhattan started toward the Bridge and for the speech-making in Brooklyn in the early afternoon:

Early in the afternoon the President of the United States, Gen. Chester A. Arthur, and the Hon. Grover Cleveland, Governor of the State of New York, the former accompanied by the members of his Cabinet and the latter by the officers of his Staff, were escorted from the Fifth Avenue Hotel to the New York City Hall, where they were joined by his Honor Mayor Franklin Edson and the New York officials.[2]

The Fifth Avenue Hotel was located at 200 Fifth Avenue. The President, Chester A. Arthur, maintained a presidential office at the hotel whenever he visited New York. The hotel was located between East 23rd and 24th streets, which is a good walk from the Bridge but not too far. Of course, President Arthur and New York Governor Grover Cleveland, who would succeed Arthur as President two years after the bridge ceremony, were not walking to City Hall. But that did not mean that no one would be going for the full walk:

The 7th regiment N. G. S. N. Y, the military escort for the occasion, assembled at their armory this morning in full uniform. A guard of twenty was detailed to march on either side of the President’s carriage. The command marched down Park and Fifth Avenues to the Fifth Avenue Hotel, the President’s quarters, where it was drawn up.[3]

The Eagle offered more detail about the military escort and some more noisy parts of the escort:

The Seventh Regiment, N.G., S.N.Y., Col. Emmons Clark, commanding, acted as escort to the Presidential and Gubernatorial party. The regimental band, of 75 pieces, headed the column and played popular airs as the procession moved along the crowded and gaily decorated thoroughfares.[2]

The Evening Star reported more detail about the procession’s trip through Manhattan (note that “the hotel” refers to the Fifth Avenue Hotel):

The sidewalks along the route were lined with people. On Madison Square it was estimated that there were 10,000 people. The President and invited guests occupied carriages which were drawn up in line on the south side of the hotel.[3]

We are also told of all of the members of the procession:

In the first carriage sat President Arthur and Mayor Edson. In the other carriages were Secretaries Frellinghuysen and Folgert, Postmaster General Gresham, Secretary Chandler, Attorney General Brewster, Marshal McMichael, District of Columbia; Mr. Allen Arthur, T.J. Phillips, Surrogate Rollins, Gov. Cleveland, Gov. Ludlow, of New Jersey; Gov. Fairbanks, of Vermont; Gens. Stryker and Slocum, Gov. Littlefield, of [Rhode Island]; staff of Gov. Cleveland, Gen. Carr and staff, Collector Robertson, Congressman Cox, Hono. Wm. Windom and ex-speaker Kiefer, state senators, and the Peruvian minister.[3]

My impression from The Eagle was that New York Mayor Edson was joining the procession at City Hall. However, it seems from this report that he had shared a carriage with President Arthur from the Fifth Avenue Hotel. However, both passages are a bit ambiguous. We are told that “[t]he committee representing the Brooklyn bridge trustees escorted the President and his cabinet into carriages, the other guests falling into line and taking the carriages assigned to them.”[3] When the carriages passed their military escort, “the command presented arms” before “[t]he military men broke into column and marched down 5th avenue and Broadway to the city hall park, where the members of the common council received the President and Cabinet.”[3]

The Presidential procession would, after winding through crowds in Manhattan, finally begin crossing the new bridge to Brooklyn. They completed the first third of the Bridge when they reached the New York Tower. There they were joined by “a battalion of the Fifth United States Artillery, under command of Major Jackson … and between the lines of brilliantly uniformed troops the distinguished guests passed upon the roadway.”[2] The arrival of the party at New York Tower prompted much loud fanfare:

The arrival at New York Tower was proclaimed to the multitudes on shore by the thundering of many cannon. Salutes were fired from the forts in the harbor, the United States Navy Yard, and from the summit of Fort Greene. The United States fleet, consisting of the ‘Tennessee,’ the ‘Yantic,’ the ‘Kearsarge,’ the ‘Vandalia,’ and the ‘Minnesota,’ Rear-Admiral George H. Cooper, commanding, was anchored in the river below the Bridge and joined in the salute. As the procession moved across the roadway the yards of the men-of-war were manned, and from the docks and factories arose a tremendous babel of sounds, caused by the clanging of bells, the roaring of steam whistles, and the cheers of enthusiastic people, while sounding from afar, in delightful contrast with the clamorous discord, silver chimes of Trinity rang out upon the river.[2]

The two locations specifically referenced in the above passage are in Brooklyn. The Brooklyn Navy Yard still runs along the East River, starting from the Brooklyn neighborhood of Vinegar Hill on one end and going into Williamsburg. If one walks along the Navy Yard, he or she will find him or herself just a couple of short blocks from Fort Greene en route.

Prior to the ceremony, The New York Tribune noted that “the guns on Governors Island” and “at Stagg-st and Bushwick-ave” would also join in the presidential salute.[6] Governor’s Island, which once hosted a military base, sits just off the south tip of Manhattan and is now largely park land.

The official ceremonies and speech-making for the opening of the Brooklyn Bridge were to take place “[i]n the ornate iron railway depot at the Brooklyn terminus” of the Bridge.[2] The station, it was reported, was “handsomely decorated” for the occasion.[3] From The Eagle:

The interior was bright with tasteful decorations, the prevailing feature being the sky-blue hangings of satin bordered with silver, and the coats-of-arms of the States appropriately interspersed amid a forest of flags.[2]

The Tribune offered more detail about the decorations at the railway depot prior to the event:

The station building at the Brooklyn end of the Bridge has been decorated lavishly with festooned flags, the coats of arms of all the States between the windows, and blue velvet hangings with gold embroidery overhead. The railroad tracks have been temporarily floored over and on them upward of 4,000 chairs have been placed.[6]

The placement of 6,000 chairs gives one an idea of the large size of the ceremony. I return to The Tribune’s account:

The speakers’ platform is near the northern end, toward this city, and the building is open at both ends.[6]

“This city” refers to Manhattan – recall that The Sun piece I began this article with noted the location of the Tribune building in Manhattan.

After praising the decoration of the station, The Tribune took a negative view – not seen in the accounts from after the fact – of one aspect of the location’s set-up, the acoustics:

A place more unfitted for oratory it would not be possible to provide. It resembles as much as possible a section of a tunnel 50 feet wide, open at both ends, and nearly 140 feet long. The voice even of the most powerful speaker will be lost and inaudible except within a very feet feet of him. To most of those within the building the speakers will simply appear to be going through the motions of delivering oration, and persons at the New-York end of the Bridge will have as good a chance of hearing what is said as most of those who have the white tickets of admission to the building. The only way to hear the speeches will be through the newspapers.[6]

Note a good line: “[P]ersons at the New-York end of the bridge will have as good a chance of hearing what is said as most of those who have the white tickets of admission to the building.” According to the Tribune, those interested in knowing what the speakers were saying would have done just as well to remain in Manhattan and wait for the speeches to be printed as they would have to obtain much sought after tickets to the ceremony proper in Brooklyn.

While our accounts were a bit vague on specific timings, The Evening Star reported that the ceremony at the iron railway depot commenced at two in the afternoon.[3] Prior to the official beginning of the ceremony, the parties of President Arthur, Governor Cleveland, and other guests and dignitaries were greeted by the 23rd Regiment, N.G., S.N.Y, commanded by Colonel Rodney C. Ward.[2] The Eagle reported that “[t]he regiment appeared upon this occasion for the first time in their new State service uniform, and performed their duties most efficiently.”[2] “The arrangements for the procession and exercises were under the direction of Major-General James Jourdan, commanding the Second Division, N.G., S.N.Y…”[2] The ceremony location was unsurprisingly crowded:

The building was thronged in every part. In the throng were many of the most conspicuous citizens of New York and other States, including representatives of the bench, the bar, the pulpit, the press, and all other professions.

The personae we noted as being in the procession were also present. We are also told that “[i]n the vast assemblage none were more conspicuous than the officers of the Army and Navy, who occupied an entire section and attracted great general attention.”[2]

The arrival of President Arthur and the rest of the main procession was “greeted with enthusiastic cheers.”[2] The procession members “occupied seats directly opposite the stand erected for the orators of the day.”[2]

The Tribune offered the most detail about the seating arrangements, listing the reserved sections of seats:[6]

- Sec. D – The President and Cabinet, Governor and Staff, United States Senators, Members of Congress, Governors of other States.

- Sec. E – Members of the Legislature, Common Councils of New-York and Brooklyn, City and County officials of New-York and Brooklyn.

- Sec. H – Army and Navy; National Guard.

- Sec. J – Press.

- Sec. K – Specially invited guests.

- Sec. M – Exclusively reserved for employees.

As I noted at the top, I will not discuss the speeches delivered for the Bridge-opening ceremony in thus article. However, I will note the speakers and event organizers (all information from The Eagle’s booklet).[2] Music for the ceremony was provided by the bands of the Seventh and Twenty-Third regiments. S.T. Stranahan presided over the ceremony, and we are told that he did so “with the skill and dignity gained during his long experience in public life.” The opening prayer was delivered by Bishop Littlejohn. William C. Kingsley, President of the Board of Trustees, spoke on behalf of the Board. Acceptance addresses were delivered by Mayor Seth Low of Brooklyn and Mayor Franklin Edson of New York. The mayors were followed by a cornet solo by J. Levy. Abram S. Hewitt delivered an oration on the opening of the Bridge on behalf of New York. He was followed by Richard S. Storrs, who delivered the oration on behalf of Brooklyn. (I noted while reading the order that the Mayor of Brooklyn spoke before the Mayor of New York, but New York’s selected orator spoke before Brooklyn’s selected orator.)

Post-ceremony festivities

The ceremony ended with a musical performance by the 7th regiment. However, The Eagle tells us that “[t]he celebration was continued in both cities throughout the day and far into the night,” featuring “[t]housands upon thousands of enthusiastic people crowded into the streets.”[2]

After the ceremony, President Arthur, Governor Cleveland, and the speakers and trustees were driven to the Brooklyn Heights residence of the Chief Engineer of the Brooklyn Bridge, Washington A. Roebling, where a reception was held.[2] The procession including the President and Governor was cheered as it made its way from the ceremony site to Roebling’s house. After leaving Roebling’s, the procession “proceeded to the residence of [Brooklyn] Mayor Low, where they were entertained at a banquet.”[2] After the Brooklyn Mayor’s banquet, “under the auspices of the Municipal authorities, a grand reception to President Arthur and Governor Cleveland was given by the citizens of Brooklyn at the Academy of Music (still present in Downtown Brooklyn, albeit in a different building than in 1883), and was attended by a great multitude.”[2]

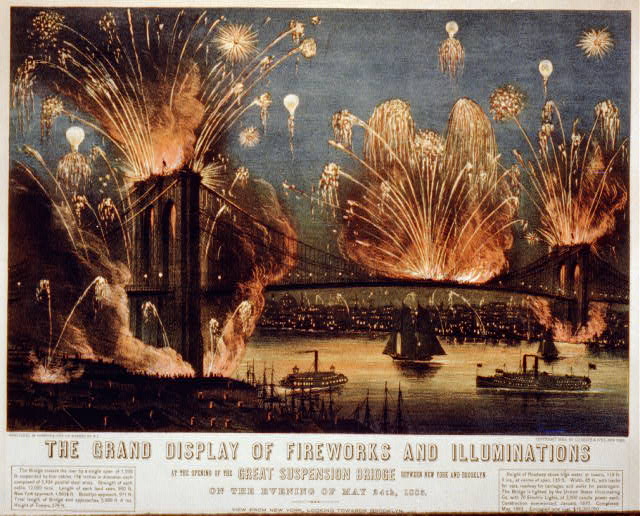

Those who missed reception at the Brooklyn Academy of Music were able to enjoy “the display of fireworks on the Bridge given under the direction of the Board of Trustees.”[2] We are told that “[t]he pyrotechnic exhibition was viewed by almost the entire populace of the two cities, and a vast concourse of visitors from abroad.” Many watched from boats on the East River, which was consequently “fairly blocked with craft of every description bearing legions of delighted spectators, and the streets and housetops were packed with people.”[2] It should come as no surprise that “[t]he display was generally characterized as one of the grandest ever witnessed in America.”[2]

While The Eagle praised the night-time decorations in both Manhattan and Brooklyn, it noted that “[t]he illuminations in Brooklyn, particularly, were on magnificent scale…” Finally, we are told that order was maintained throughout the merriment:

Throughout the afternoon and evening the best of order was preserved; the casualties that occurred were few and unimportant, and the auspicious day ended without the intrusion of anything that would carry with it other than pleasant memories of the significant event which it commemorated.[2]

General thoughts about the Bridge

The Sun expressed optimism about the long term impact of the Brooklyn Bridge on what were then the separate and distinct cities of Manhattan and Brooklyn, although it noted that the impact would be seen more in some parts of Manhattan and in Brooklyn than in others:

[W]hile this lordly structure will excite the wonder and curiosity of every New Yorker, it will probably be a long time before it comes into such general use that the inhabitants of New York above Washington square will be seen any oftener on Brooklyn Heights than they have been formerly. But to the residents of Brooklyn great opportunities will now be opened. They can come over here to do their shopping and see the picture galleries, and there is no reason why Mayor EDSON, on behalf of the citizens of New York, should feel any hesitation about assuring Mayor Low, the representative of Brooklyn, of his distinguished consideration and that of the rest of mankind. And all the rest will come in due time.[1]

Mixed in with The Sun’s understandably Manhattan-centric perspective is an interesting reference to Brooklyn Heights, a Brooklyn neighborhood which we have covered often, and which sits adjacent to the Brooklyn Bridge. There is a reason, implied in this piece, why Brooklyn Heights is known as America’s first suburb.

One week after the opening of the Bridge, 12 people died and 36 were injured after a woman tripped on the Bridge causing panic and a stampede.[7] The Bridge would have other issues in its early years – but it immediately became of great service to the residents of Brooklyn and Manhattan, and eventually New York City as a whole. The Bridge not only supported pedestrians and eventually vehicles, but also, for a time as I wrote about previously, trains and trams. It is a testament to the sturdiness of the Bridge’s design that it stands today looking quite like it did on May 24, 1883, and supporting, in addition to vehicles, thousands of pedestrian crossings each day (I would prefer it become a little bit less popular, but I digress).

1883 ad: Shining brighter than the Brooklyn Bridge

The May 24, 1883 edition of The Evening Star provided a wire report which was of great service to my putting together this article. The May 25 edition had a follow-up reference to the Bridge. I say reference instead of report for a specific reason. A certain Mr. Lew Newmyer of Washington D.C., who we can infer sold children’s clothing, had apparently been following the Bridge news, and he had an idea for how he could capitalize on the hubbub:

The illumination of the Brooklyn bridge don’t begin to compare with the smile that illuminates your boy’s countenance when you buy him one of those $1.90 sailor suits, worth $4, or your bigger boy a $4 suit, worth $7.[8]

I tip my hat to the ingenuity of the ad – never would I have thought to promise that your son’s smile would be brighter than the Brooklyn Bridge if you buy my wares.

Footnotes

- [1] The sun. [volume] (New York [N.Y.]), 24 May 1883. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030272/1883-05-24/ed-1/seq-2/

- [2] “Opening Ceremonies of the New York and Brooklyn Bridge, May 24, 1883.” 2023. May 12, 2023. https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/28191/pg28191-images.html

- [3] Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 24 May 1883. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1883-05-24/ed-1/seq-3/

- [4] Daily Los Angeles herald. [microfilm reel] (Los Angeles [Calif.]), 25 May 1883. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85042459/1883-05-25/ed-1/seq-2/

- [5] The Learning Network and By The Learning Network. 2012. “May 24, 1883 | Brooklyn Bridge Opens.” The Learning Network. May 24, 2012. https://archive.nytimes.com/learning.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/05/24/may-24-1883-brooklyn-bridge-opens/

- [6] New-York tribune. [volume] (New York [N.Y.]), 24 May 1883. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030214/1883-05-24/ed-1/seq-1/

- [7] New-York tribune. [volume] (New York [N.Y.]), 31 May 1883. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030214/1883-05-31/ed-1/seq-1/

- [8] Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 25 May 1883. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1883-05-25/ed-1/seq-4/