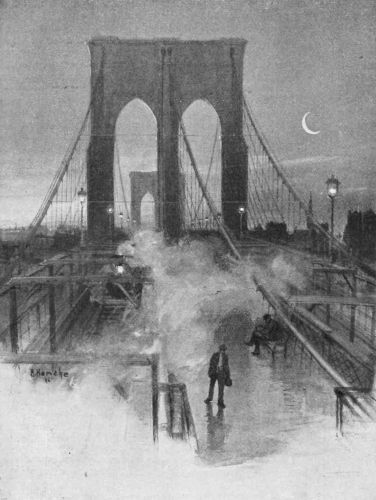

I have walked across the Brooklyn Bridge during the night on many occasions. With few crowds and a beautiful view of the New York City lights against the dark sky, the evening was always the best time to cross the Brooklyn Bridge. Never on those evening walks, however, did I think much of the Brooklyn Bridge’s cables. On August 6, 1895, Franklin Matthews, an evening-Brooklyn Bridge walker from more than a century ago, published his take on the Brooklyn Bridge’s “Cobweb Lane,” a special place that appears only during the night. In this post, I will review Matthews’ Cobweb Lane essay for Harper’s Round Table, with reference to my own night-clad treks across the Bridge.

Do note that I will not cover Matthews’ entire essay in this article. Instead, I will focus specifically on his description of the Brooklyn Bridge (and its mysterious Cobweb Lane) at night. I will address some of his other interesting 1895 Brooklyn Bridge observations in a separate post.

What is Cobweb Lane?

The most curious and interesting highway that I know of is Cobweb Lane.

Franklin Matthews

So began Matthews’ essay.

What is Cobweb Lane? Matthews started his description paradoxically: “[S]ome … have been in it in the daytime, but strangely enough they have never seen it…”

Many people had been in the Cobweb Lane, but few people have seen it? Whatever did Matthews mean? The “peculiar reason” people had been in Cobweb Lane without seeing it, according to Matthews, was that “Cobweb Lane doesn’t exist in the daytime.” Instead, “[i]t only exists at night.”

Where is this Cobweb Lane? Matthews assured readers of the nineteenth century American children’s magazine that it was closer than they might think from his description:

[Cobweb Lane] isn’t some out-of-the-way and quaint place in London, as, at first thought, its name might indicate, but it is in the most conspicuous place in Greater New York.

What is this most conspicuous place? Matthews promised to let readers in on the secret.

The Brooklyn Bridge’s Cobweb Lane

Matthews advised readers on how to see Cobweb Lane:

Cobweb Lane is nothing more nor less than the promenade on the Brooklyn Bridge. It doesn’t exist until after midnight, because not until then do the strands that hang from the big cables resemble the huge cobwebs that have suggested the name Cobweb Lane. The moon has to be in just the right position; the great cities of New York and Brooklyn must have gone to bed and left numerous lights, some in full glare and some turned down; the water in the river below must have a thin veil of mist hanging over it, and then, in the stillness of the night, if you will walk over the bridge you will see Cobweb Lane.

Night gives the Brooklyn Bridge promenade, today more commonly known as the pedestrian walkway, a different appearance. Only under the shroud of darkness does the Brooklyn Bridge promenade transmogrify into Cobweb Lane.

The Lights of Today and the Lights of 1895

Matthews’ take was an interesting one. As I noted at the top, I never thought much of the cables of the Brooklyn Bridge at night – I was always more taken by the cool air and lights. One note of potential difference between the contemporary view and Matthews’ view in 1895.

Matthews made special mention of “numerous lights, some in full glare and some turned down.” When he discussed the East River below the Brooklyn Bridge, however, he made no reference to the lights: “the water in the river below must have a thin veil of mist hanging over it…” One of the most striking features of a walk across the Brooklyn Bridge today (or a visit to DUMBO’s Main Street Park in the evening) are the lights of Manhattan dancing on the water’s surface. Matthews’ omission is perhaps indicative of New York City’s nighttime lights being less numerous and luminous in 1895 than today.

A Walk Down Cobweb Lane in 1895

Matthews wrote a vivid description of the Brooklyn Bridge’s Cobweb Lane for an audience that would be unlikely to traverse it for several years at least. Like much of Matthews’ young audience in 1895, we cannot traverse the Cobweb Lane that Matthews did, although Cobweb Lane itself still exists. However, even if the Cobweb Lane of 1895 no longer exists as it once did, we have a clear account of it from Matthews:

There is East Cobweb Lane and West Cobweb Lane. The first is on the Brooklyn side of the bridge and the other is on the New York side. As you walk out on the promenade and look over the cities and the beautiful harbor, perhaps you soon will turn your eyes to the top of one of the towers as you approach it. You are now at the beginning of Cobweb Lane. The four big cables curve down from the top and hide themselves in some masonry at your feet, and when you look up the narrow spaces between them, as they reach away before you, the eye catches sight of strands of steel rope, woven regularly and gracefully, hanging from the cables and extending to the structure on which you are standing. These strands, when the moon shines just right, partly obscured and lying low in the south, are like the filmy threads of a monster cobweb spun in the sky.

The Moon is beautiful, isn’t it?

Searching for the Spider of Cobweb Lane

Did a spider rule Cobweb Lane? Matthews assured readers that it did not, as much as it may have seemed that a spider did:

Just as you are entranced with this fairy picture, and are wondering where the big spider must be, you look ahead of you on the promenade, and, as if coming from some hidden passage, you see a cloud of vapor. There is something approaching, surely. You wonder at once if the spider that could have strung this web in the air would have hot breath, and it is not until you hear a noise and are conscious that a train of cars has passed you that you begin to realize that it really isn’t a spider chasing along one of the paths of his web after you, in the hope of catching you and making of you a very choice morsel of a fly.

The Brooklyn Bridge Cable Railway System

What did Matthews mean by a “train of cars”? To be sure, the Brooklyn Bridge today does have vehicle traffic. But Matthews was unlikely referring to cars in 1895. It is possible that he was referring to the Brooklyn Bridge’s cable railway system, which was implemented at the time the Brooklyn Bridge opened in 1883. He could not have been referring to the old trolley car system on the Brooklyn Bridge that opened three years after the publication of the Cobweb Lane essay.

(Updated for clarity on August 16, 2021.)

Appreciating the Brooklyn Bridge in Night and Day

Although Matthews’ essay began with a description of the Brooklyn Bridge’s charm at night, he noted that he appreciated observing how its appearance changed in different times of day:

For nearly five years I have been going over the Brooklyn Bridge night and day, and it seems to me that every few days I see something in the arrangement of the details of the structure that I never saw before. It is a constant delight to watch the bridge under the varying conditions that affect it from day to day.

At night specifically, Matthews found that “[i]t is … interesting at the dead of night to see the workmen splice one of the car cables, taking out some broken strand and weaving in another.”

The Brooklyn Bridge is Not a Prosaic Thing

Matthews asked C.C. Martin, who was then the Chief Engineer of the Brooklyn Bridge, if he could tell him anything interesting about the Bridge that might escape the ordinary observer. Martin replied:

There isn’t much to be said. The bridge is a very prosaic thing.

Although Matthews did not agree with Martin, he understood Martin’s perspective:

He concerns himself with abstract mathematical formulas a good deal. He knows about the tangents and sines and cosines and curves and strains and all that, which some of us grown-up people studied about in college, and have been glad to forget in our humdrum lives since.

Matthews asked Martin if he knew where Cobweb Lane was. Unsurprisingly, Martin smiled and said that he did not. Matthews concluded:

[Martin] showed in that way that the bridge was a very prosaic thing to him; but I am sure that if you take no thought of mathematics, and look for the beautiful and interesting things about the bridge, you will be convinced that the bridge is not prosaic after all. A visit to Cobweb Lane will prove it.

Well said.