I began my review of the January 1897 issue of Birds: A Monthly Serial, or Birds: Illustrated By Color Photography, on January 5, 2021. Today, on March 17, 2021, we review the tenth and final bird from the issue – the Golden Oriole. Orioles are well known in the United States, so it should be more familiar to much of our audience than some of the more exotic birds that we covered previously. However, similarly to the Red-Rumped Tanager of the prior article in the series, we will have to work through some avian nomenclature issues that arise from the 1897 date of publication of the magazine.

The editors of Birds saw fit to omit a self-introduction by the Golden Oriole from its section in the magazine. For that reason, today’s review will be focused on Oriole facts and stories – much like the only other bird who did not receive space for a self-introduction, the Guianan Cock-of-the-Rock.

You can follow along with the original Golden Oriole content at Project Gutenberg and The Internet Archive.

The Golden Oriole, Illustrated

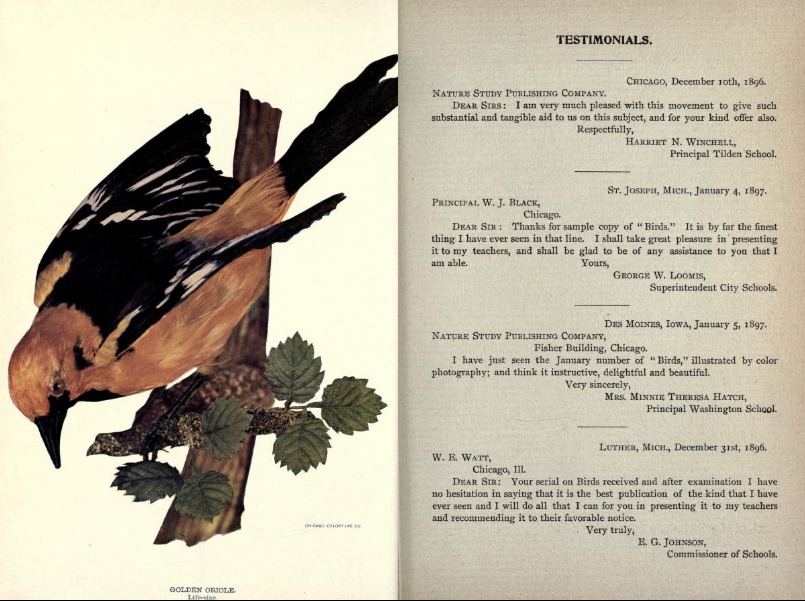

The editors saw fit to make up for the lack of first-bird content from the Golden Oriole with something of an action shot. The Golden Oriole’s black and white wings are a bit open, revealing the golden feathers underneath.

The “Golden Oriole” in Today’s Terms

Before proceeding with our Golden Oriole review, we should clarify what type of Oriole we are referring to. The Golden Oriole article in the magazine, which we will discuss in the next section, notes that “[w]e find the Golden Oriole in America only.” The “Golden Oriole” is a migratory bird – so that rules out non-migratory Orioles. Furthermore, it begins “appearing in considerable numbers in West Florida about the middle of March.” Finally, the article contains an anecdote from a gentleman about Golden Orioles breeding and raising their young in Southern Indiana – so we know that the Golden Oriole’s breeding range must encompass Indiana.

The name “Golden Oriole” appears to be used for foreign Orioles these days. For example, a quick search of eBird notes the Eurasian Golden Oriole, Indian Golden Oriole, and African Golden Oriole. Wikipedia goes as far as to state that the Eurasian Golden Oriole is commonly known as the “Golden Oriole,” without the geographic qualifier. In addition to the fact that the aforementioned Golden Orioles are not found in the Americas, as their names indicate, they look little like the Golden Oriole pictured above.

Thus, “Golden Oriole” in 1897 refers to a different bird than “Golden Oriole” does today. What is our “Golden Oriole”?

An Attempt to Answer the Question From 2012

Lee’s Birdwatching Adventures Plus, which also covered the Birds article in 2012, suggests that Birds is referring to the Spot-Breasted Oriole. While this may be correct, I am left uncertain after researching the matter.

According to Audubon, the Spot-Breasted Oriole does live lives in the Southeast of Florida but it resides there for all seasons and is not migratory. When did it arrive in Florida? Audubon states that “this large oriole apparently escaped from the Miami area in the late 1940s.” Our article was written in 1897, well before 1940, and its language suggests that the “Golden Oriole” in question arrived in West Florida from somewhere else every March. Furthermore, we are told that the “Golden Oriole” was also found nesting in Indiana, which would seem to disqualify the Spot-Breasted Oriole.

Dismissing the Hooded Oriole

Lee’s also disqualified the Hooded Oriole as a candidate because its range covers the American Southwest, but not Florida. I consulted Cornell’s eBird and came away with the same conclusion. Furthermore, ABC Birds states that the Hooded Oriole can be found “as far north as Arcata, California,”and the Hooded Oriole would not be found in Indiana at any time of the year – another key point to bear in mind.

A Strong Contender: The Baltimore Oriole

No American Oriole perfectly matches the two key facts Birds gave us about the habitat of “Golden Oriole.” Based on the facts presented, however. Here, I will discuss the case for America’s most common Oriole – the Baltimore Oriole.

Birds notes that the “Golden Oriole” is migratory. The Baltimore Oriole is described by The Cornell Lab as a medium-to-long distance migrant, and a map showing the bird’s range from South America to Canada backs up the assertion.

Indiana lies squarely in the middle of its wide breeding range – which covers most of the Eastern United States and parts of the Southeast.

The Florida aspect of the Birds account does not line up perfectly with what we know of the Baltimore Oriole. According to Cornell’s map, however, Florida is the only part of the United States that is part of the Baltimore Oriole’s wintering range. Thus, there would seem to be Baltimore Orioles in Florida during the winter. Cornell also suggests that flocks of the birds begin arriving in Eastern and Central North America in April and May, a bit after March.

Despite the minor Florida discrepancies, I think that the Baltimore Oriole remains a possible “Golden Oriole” candidate. It may be that the editors of Birds were imprecise when they stated that Golden Orioles “begin arriving” in Florida in March. An alternative theory is that the editors were unwittingly describing Orioles who pass through Florida while migrating, either from further South (e.g., Cuba and Central America) or Orioles starting their journeys from Florida.

My Pick: The Orchard Oriole

Although the Baltimore Oriole has a strong case, the best candidate for the “Golden Oriole” appears to me to be the Orchard Oriole. Unlike the Baltimore Oriole, it appears to match the facts stated in Birds regarding Florida and Indiana.

The Orchard Oriole is a migratory bird like the Baltimore Oriole. Its range is a bit shorter – it winters in parts of Mexico, Central America, and the northern tip of South America. It breeds in the East and Central United States, but it has a slightly smaller breeding range than the Baltimore Oriole.

The Orchard Oriole’s case is compelling based on four facts. To begin, the Orchard Oriole, like the Baltimore Oriole, is a migratory bird. Second, citing to sources, Wikipedia notes that Orchard Orioles “depart from their winter habitats in March and April and arrive in their breeding habitats from late April to late May.”

A key point that favors the Orchard Oriole over the Baltimore Oriole is that Audubon shows the southern half of Florida as being part of its common migration route. This, in conjunction with the Wikipedia article, addresses two key points. First, since some Orchard Orioles begin migrating as early as March, it would make sense to see them on their migration routes during March. Second, because a large chunk of Florida is part of the Orchard Oriole’s migration path, it would make sense for them to suddenly appear in Florida beginning in March.

Finally, if you look closely at the Audubon map – in the link above, you will find an interesting point about Indiana. Audubon distinguishes between common breeding grounds for the Orchard Oriole and uncommon breeding grounds. Southern Indiana, the source of the “Golden Oriole” nesting anecdote, is a common breeding ground. Northern Indiana is an uncommon breeding ground.

Investigative Conclusions

Based on the limited information about the Golden Oriole, I think that the Orchard Oriole is the most likely candidate to be the bird discussed in the January 1897 issue of Birds. However, there is more than enough ambiguity in the Birds article, combined with the fact that some information about the bird in question may have changed since 1897, to believe that the “Golden Oriole” could actually be the Baltimore Oriole, or perhaps a different variety of Oriole that I missed. Furthermore, the editors may have lumped several orioles together – which may have happened to some extent in our previous article on the Red-Rumped Tanager.

Some readers may note from pictures that the Birds magazine Oriole photograph shows a bird with a mostly-orange head while the Baltimore Orioles and the Orchard Orioles seem to usually have black heads. I note that too – but I am not sure how to resolve that issue.

Golden Oriole Facts

Having escaped from the “Golden Oriole” identity weeds with what I hope is the correct answer, we now proceed to examine the Birds editors’ recitation of facts and stories about the “Golden Oriole.”

Do note that while I did conclude that we are likely discussing the Orchard Oriole and/or the Baltimore Oriole in modern parlance, I will refer to it as the “Golden Oriole” in the spirit of the magazine for the duration of this article.

Where Does the Golden Oriole Live?

“We find the Golden Oriole” in America only. As I noted above, I believe that the editors mean “America” as referring to North America rather than as to the United States exclusively. If I am correct in my belief that we are discussing the Orchard Oriole or the Baltimore Oriole, it does winter as far south as the upper edges of South America.

A gentleman by the name of Mr. Nuttall noted that the migratory Golden Oriole “appear[s] in considerable numbers in West Florida in the middle of March.” We also learn from an anecdote later in the piece that Golden Oriole nests were observed in Southern Indiana.

The Song of the Golden Oriole

The Birds editors have waxed poetic about the songs of some of our earlier feathered friends. They are a bit more subdued about the Golden Oriole – telling us that “[i]t is a good songster, and in a state of captivity imitates several tunes.” There is a good Golden Oriole fact – they can apparently learn different songs in captivity. The Parakeet we covered earlier may have company.

What Does the Golden Oriole Eat?

Like many other birds, “[t]his beautiful bird feeds on fruit and insects…”

On Nest-Building and Young-Rearing

We are told that Golden Oriole nests are “constructed of blades of grass, wool, hair, fine strings, and various vegetable fibers, which are so curiously interwoven as to confine and sustain each other.” Where do the Golden Orioles build these intricate nests? “The best is usually suspended from a forked and slender branch, in shape like a deep basis and generally lined with fine feathers.”

Audubon has an interesting article on hanging Oriole nests that is illustrated with a good number of photographs. That contemporary source notes two experts who “agree that even if the oriole’s craft is instinctual, it takes time and training to perfect it. In other words, only an expert nest builder would be able to take a snarl of fishing line and turn it into sanctuary.”

The Editors quoted Mr. Nuttall in describing the Golden Oriole in breeding season:

On arriving at their breeding locality they appear full of life and activity, darting incessantly through the lofty branches of the tallest trees, appearing and vanishing restlessly, flashing at intervals into sight from amidst the tender waving foliage, and seem like living gems intended to decorate the verdant garments of the fresh clad forest.

Once the Golden Oriole chicks are born, the Golden Orioles – the mothers in particular – are loving parents. The editors wrote: “It is said these birds are so attached to their young that the female has been taken and conveyed on her eggs, upon which with resolute and fatal instinct she remained faithfully sitting until she expired.”

We could not make it through an article without a bit of bird expiration.

Recognizing the Gentleman from Indiana

I noted on several occasions that the final bird article of the January 1897 issue of the Birds magazine concludes with the account of an “Indiana gentleman.” Since this Indiana gentleman played a key role in helping us narrow down the candidates for the title of “Golden Oriole,” I suppose I ought to yield the floor. Below, I will reprint his account in its entirety.

Account of the Indiana Gentleman – Reprinted Verbatim

“When I was a boy living in the hilly country of Southern Indiana, I remember very vividly the nesting of a pair of fine Orioles. There stood in the barn yard a large and tall sugar tree with limbs within six or eight feet of the ground.”

“At about thirty feet above the ground I discovered evidences of an Oriole’s nest. A few days later I noticed they had done considerably more work, and that they were using horse hair, wool and fine strings. This second visit seemed to create consternation in the minds of the birds, who made a great deal of noise, apparently trying to frighten me away. I went to the barn and got a bunch of horse hair and some wool, and hung it on limbs near the nest. Then climbing up higher, I concealed myself where I could watch the work. In less than five minutes they were using the materials and chatted with evident pleasure over the abundant supply at hand.”

“They appeared to have some knowledge of spinning, as they would take a horse hair and seemingly wrap it with wool before placing it in position on the nest.”

“I visited these birds almost daily, and shortly after the nest was completed I noticed five little speckled eggs in it. The female was so attached to the nest that I often rubbed her on the back and even lifted her to look at the eggs.”

My Thoughts on the Indiana Gentleman’s Account

The Indiana Gentleman explains the path to a Golden Oriole’s heart. While the Golden Oriole’s may begin wary of humans – judging by some past bird articles, this may be wise – one can get in their good side by offering some nest-building materials. With that being said, I have my doubts that most Golden Oriole mothers will be quite as amenable to being pet and handled as the one that the Indiana Gentleman came across.

A Golden Bird Conclusion

The Golden Oriole provides a nice capstone to January 1897 issue of Birds. While we did not get to hear from the Golden Oriole himself – we did get to do some detective work to figure out his identity. While I am not entirely sure that I am correct in choosing the Orchard Oriole out of a lineup, it was a fun problem to work through. Provided that the issue of identity of the Golden Oriole can be clarified, the article should make for engaging reading for today’s children, just as it must have 124 years ago.

If you think that I have the identity of Mr. “Golden Oriole” all wrong, I invite you to correct me in the Guestbook. If we receive a better answer (supported by evidence) than the one I came up with, I will publish it as an addendum to the instant series.

I look forward to concluding this article series with a piece on the poems from the January 1897 issue of Birds.