The fourth bird in the January 1897 issue of Birds: A Monthly Serial is the Golden Pheasant. The serial’s Golden Pheasant article is shorter than the articles for the first three birds that we covered, so this post may be shorter as well. But the Golden Pheasant is no less striking than the Nonpareil, Resplendent Trogon, and Mandarin Duck, so perhaps the content will pack just as much of a peck. I apologize for the pun. To avoid further humor-related injuries, let us proceed to the review of the Golden Pheasant, and assess whether this 1897 children’s literature holds up in 2021.

You can follow along with the original Golden Pheasant content at Project Gutenberg and The Internet Archive.

The Golden Pheasant, Illustrated

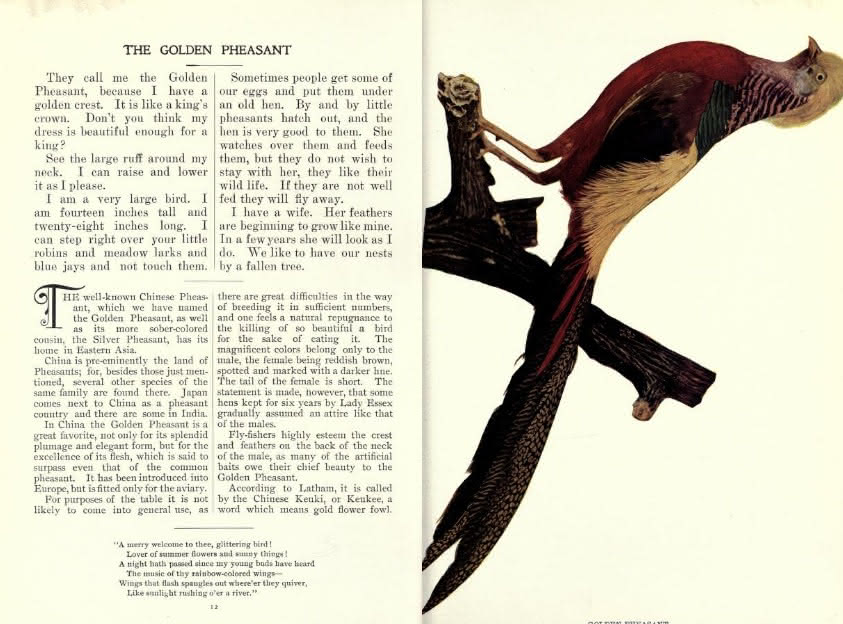

Below, you will find the magazine’s illustration of the Golden Pheasant.

The Golden Pheasant continues our trend of colorful birds, with shades of red, green, yellow, and brown. Its “hair” on the top of its head may set it apart from the first three. What is that, exactly? Let us ask the Golden Pheasant himself.

Comments from Mr. Golden Pheasant

The Birds magazine continued its concept of beginning specific bird content with a brief statement from the bird himself. In the case of the Golden Pheasant, there was an emphasis on “brief.” While the first three birds we covered each had a full-page statement or letter, the Golden Pheasant received just under half a page. Before one suggests that the Golden Pheasant was slighted, a few of the later birds that we will cover were not asked for comment at all. As we will see at the end, Mr. Golden Pheasant did get a poem in his honor to make up for the lower word count. I will cover the magazine’s poems in a separate post after finishing the rest of the bird content.

I now yield the floor to Mr. Golden Pheasant. How do we know it is “Mr.” Golden Pheasant? Well, he says so.

Mr. Golden Pheasant’s Regal Regalia

Where does Mr. Golden Pheasant’s name come from? “They call me the Golden Pheasant, because I have a golden crest.” What does that golden crest remind Mr. Golden Pheasant of? “It is like a king’s crown.” What a regal bird, indeed. Mr. Golden Pheasant agreed: “Don’t you think my dress is beautiful enough for a king?”

Mr. Golden Pheasant’s Size

Mr. Golden Pheasant made sure to tell children that he was a “very large bird,” standing “fourteen inches tall and twenty-eight inches long.” He gave an example of what this size would allow him to do: “I can step right over your little robins and meadow larks and blue jays and not touch them.” Do you hear that, nineteenth century American children? This mighty bird would scoff as he stepped over the puny little birds in your backyard. Take that. He is much smaller than our own Mr. Emu here at The New Leaf Journal, however. Couldn’t be this cocky if the Bird magazine was published in Australia. He noted blue jays too – I covered those in a separate matter.

With Mr. Golden Pheasant’s height, one might wonder whether he could readily reach things on the ground. Have no fear. “See the large ruff around my neck. I can raise and lower it as I please.”

Egg Thieves!

Mr. Golden Pheasant explained that sometimes, his Golden Pheasant eggs were stolen. “Sometimes people get some of our eggs and put them under an old hen.” Lest one worry about the hatchlings, “the hen is very good to them.” However, Mr. Golden Pheasant stated that although the hen is good to the little Golden Pheasants, “they do not wish to stay with her; they like their wild life.”

Why were eggs so often taken by people that Mr. Golden Pheasant had to make a note of it? A clue comes in the next section. There, Mr. Golden Pheasant explained that he and his wife “like to have our nests by a fallen tree.” Fallen tree? Well, I suppose that would make it easier for people to take the eggs. Other birds, like the Resplendent Trogon, stick to nests not only high in the trees, but also high in the mountains.

Mr. Golden Pheasant’s Wife

Mr. Golden Pheasant was married. Regarding his wife, “[h]er feathers are beginning to grow like mine.” What did this mean? “In a few years she will look as I do.” In light of this revelation, I suppose that it was necessary for Mr. Golden Pheasant to state his sex outright.

Golden Pheasant Facts

Mr. Golden Pheasant returned to his fallen-tree nest and the editors of Birds: A Monthly Serial took the stage to tell us more about the gold-crested bird. Will the content be child-friendly for once? Well, perhaps a bit more than previous entries…

Where Does Mr. Golden Pheasant Live?

The Golden Pheasant is also known as the “Chinese Pheasant.” If that was not enough of a hint, the magazine continues to tell readers that it “has its home in Eastern Asia.” So too does the Silver Pheasant, which the magazine observes is the Golden Pheasant’s “more sober-colored cousin.”

While China was the principle place to find Golden Pheasants, “Japan comes next to China as a pheasant country and there are some in India.” Golden Pheasants were introduced to the United Kingdom around the time the magazine was published. The magazine did make reference to this event – “It has been introduced into Europe, but is fitted only for the aviary.” Today, Golden Pheasants are found in North America, South America, and parts of Western and Northern Europe.

An Entry on Entrees

In the last bird review, we learned that the Chinese valued the Mandarin Ducks for their aesthetic qualities and for their fidelity to one another. Here, we learn that the Chinese valued the Golden Pheasant “not only for its splendid plumage and elegant form, but for the excellence of his flesh, which is said to surpass even that of the common pheasant.” So begins the discussion of Golden Pheasants for dinner.

The magazine noted optimistically that, despite the Golden Pheasant’s being considered a delicacy, “[f]or purposes of the table it is not likely to come into general use…” Why so? “[T]here are great difficulties in the way of breeding it in sufficient numbers…” That fact likely explains why Mr. Golden Pheasant complained about humans stealing eggs from feral Golden Pheasant nests. If they could not be readily bred domestically, the eggs would have to be pilfered from the wild.

The magazine further suggested that the general adoption of Golden Pheasants for the dinner table was hindered by the fact that “one feels a natural repugnance to the killing of so beautiful a bird for the sake of eating it.”

The conservation status of the Golden Pheasant is currently “Least Concern,” and none of the contemporary sources make special note of people eating them. This all comes together to suggest that the optimism of the editors of Birds: A Monthly Serial, was well-founded. They are common in aviaries, however, suggesting that they can, in fact, be bred in captivity without too much difficulty.

The Colors of the Golden Pheasant

Like most of the other birds we covered, the male Golden Pheasants are generally more colorful than the females. “The magnificent colors belong only to the male, the female being reddish brown, spotted and marked with a darker hue.” Furthermore, “[t]he tail of the female is short.” What did Mr. Golden Pheasant mean when he suggested that his wife would soon look the same as him then? “The statement is made, however, that some hens kept for six years by Lady Essex gradually assumed an attire like that of the males.”

A quick search of contemporary sources revealed no reference to female Golden Pheasants adopting the bright colors of their male counterparts. Wikipedia notes, however, that “[t]here are … different mutations of the golden pheasant known from birds in captivity, including the dark-throated, yellow, cinnamon, salmon, peach, splash, mahogany and silver.” This passage does not sound similar to the story of Lady Essex’s lady Golden Pheasants.

According to Animals Network, the reason why female Golden Pheasants are not colorful is because they “can’t afford showy features and gaudy colors, not when they have a brood to raise.” It continues, “[t]heir brown color helps them blend in with their surroundings, better allowing them to incubate eggs and raise chicks.” Perhaps Lady Essex’s Golden Pheasant hens became more colorful because they did not have to fear predators? It seems a bit unlikely, but who knows?

Fly-Fishers and Golden Pheasant Feathers

The editors of Birds stated that Golden Pheasants were much admired by the fishing community. “Fly-fishers highly esteem the crest and feathers on the back of the male, as many of the artificial baits owe their chief beauty to the Golden Pheasant.”

The Chinese Name

The editors wrote that that the Chinese called the Golden Pheasant “Keuki” or “Keukee.” That meant “gold flower fowl.” The editors cited to Latham’s “General History of Birds,” published in 1896, for this fact. I found no alternative source that cites to it. Latham’s stated that the name also means “wrought fowl,” noting its hardiness. If any Mandarin speakers read this, feel free to explain in the Guestbook whether Latham’s was correct.

The Golden Coronation

The Golden Pheasant article was lighter on content than the first three bird posts, but still enlightening. Nothing in the post was completely out-dated. Furthermore, it offered a few interesting anecdotes that would not be easy to find today. The story of Lady Essex’s hens is interesting, although perhaps dubious. Latham’s discussion of the Golden Pheasant’s name in Chinese is worth looking into. The fly-fisherman anecdote was noteworthy.

The article discussed the subject of Golden Pheasant hunting without descending into gratuitous bird violence, as it did with the Resplendent Trogon. While this was not the most dense article, it makes for good reading today as it must have done in 1897.

In the next issue, we will leave China but remain in the Pacific to cover the Australian Grass Parakeet. Consider it my continuation to an otherwise unrelated article that I wrote about a “FOUND PARAKEET” sign.