We fly into the home stretch of our review of each bird in the January 1897 issue of Birds: A Monthly Serial, also known as Birds: Illustrated By Color Photography. Last week, we showcased the Guianian Cock-of-the-Rock. Today, we leave the Americas to visit the Red Bird of Paradise, which makes its home in New Guinea and on neighboring islands. This avian Red Bird of Paradise is not to be confused with the botanical Red Bird of Paradise, which grows in Mexico and the American Southwest. Will the Red Bird of Paradise measure up to the other colorful birds we have covered? Read on to find out.

You can follow along with the original Red Bird of Paradise content at Project Gutenberg and The Internet Archive.

The Red Bird of Paradise, Illustrated

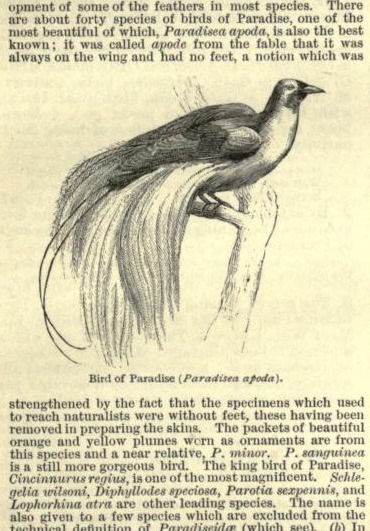

The magazine begins its Red Bird of Paradise section with a spectacular picture, seen below.

The Red Bird of Paradise is yellow, black, and, as its name suggests, red. Its head, neck, and breast are entirely yellow and black, as bold as a bee. Its back, wings, and dramatic tail are a reddish brown, darker on the wings and back and lighter toward the tail.

Below, you will find my clip of The Internet Archive copy of the magazine pages. The Internet Archive scan of the Red Bird of Paradise is a bit dimmer than the Project Gutenberg version, and the “reddish brown” feathers look comparatively browner. I will venture that the Gutenberg picture is closer to what it appeared when the magazine was brand new.

Mr. Red Bird of Paradise’s Self-Introduction

Birds resumes its tradition of obtaining comment from the featured bird itself after the Cock-of-the-Rock was too shy or humble to comment in the previous article. Below, we will hear from Mr. Red Bird of Paradise. Reader discretion advised, however. While the editors of Birds have on occasion take it upon themselves to traumatize their audience of children, we will find that Mr. Red Bird of Paradise decided to do so himself.

Where Does Mr. Red Bird of Paradise Live?

Mr. Red Bird of Paradise tells readers that he lives on a “very warm” island.

What About Ms. Red Bird of Paradise?

Mr. Red Bird of Paradise tells us that Ms. Red Bird of Paradise has brown feathers and no long tail feathers. This contrasts with Mr. Red Bird of Paradise, who brags that women like to wear his beautiful feathers. Ms. Red Bird of Paradise is also fond of he husband’s feathers, finding them to be “very beautiful.”

Red Bird of Paradise Parties

While I am not sure that any bird dances quite like the Cock-of-the-Rock from last week, Mr. Red Bird of Paradise is a bit of a show-off himself. He explains: “When we have a party, we go with our wives to a tall tree. We spread our beautiful plumes while our wives sit and watch us.” That sounds like a good time. What could go wrong?

Danger Lurks for Party-Goers

All parties have to end. Mr. Red Bird of Paradise explains that if he does not party carefully, bad things can happen. According to our beautifully-feathered friend, men would sometimes lie in wait, watching Red Bird of Paradise parties. At the moment that a Red Bird of Paradise much like Mr. Red Bird of Paradise would spread his feathers, the men would shoot an arrow at the Red Bird of Paradise. After skipping over some details, Mr. Red Bird of Paradise explains that the men would then dry the Red Bird of Paradise skins and take off the feet and wings.

This, according to Mr. Red Bird of Paradise, is why some people erroneously believed that the Red Bird of Paradise has neither feet nor wings. Apparently, those people were relieved of those notions much like young readers of the magazine in 1897 were relieved of sleep after reading this article.

The Other Way in Which Birds of Paradise Earned their Name

Mr. Red Bird of Paradise explains how he earned his name: “[P]eople also thought we lived on the dews of heaven and the honey of flowers. This is why we are called the Birds of Paradise.”

Red Bird of Paradise Facts

Mr. Red Bird of Paradise exited the stage to spread his feathers. We can only hope that he carefully checked his surroundings before doing so. Upon his departure, the editors of Birds took over to provide readers with facts about the Red Bird of Paradise from a third-party perspective. We will go over the short essay on the Red Bird of Paradise and supplement it with information from contemporary sources.

Where to Find the Red Bird of Paradise

The editors of Birds wrote that Birds of Paradise generally are found exclusively on New Guinea and neighboring islands. The Red Bird of Paradise specifically “is found only on a few islands.”

The 1897 information is consistent with contemporary sources. National Geographic writes that “Birds-of-paradise can be found throughout Papua New Guinea, the surrounding Indonesian islands, and a small part of northeastern Australia.” Cornell University’s eBird site places the Red Bird of Paradise on the western tip of Indonesia’s West Papua Province.

The Red Bird of Paradise’s conservation status is “near threatened.” According to the IUCN Red List, “[t]his species has a very small range and probably has a small population. It is likely to be declining slowly as a result of limited habitat loss, and trends in human activity and population change should be monitored carefully to clarify the level of threat.” Its status was last assessed in 2016.

More on the Red Bird of Paradise’s Name

The editors restate Mr. Red Bird of Paradise’s account of people in New Guinea thinking that the Red Bird of Paradise had no legs because they only saw poor desiccated bird corpses after the legs had been removed. That, of course, played a role in how the bird came to be named. Quoting from the editors:

[O]n account of their want of feet and their great beauty, they were called the Birds of Paradise, retaining, it was thought, the forms they had borne in the Garden of Eden, living upon dew or ether through which it was imagined they floated by the aid of their long cloud-like plumage.

The editors on the Red Bird of Paradise’s name

Out of curiosity, I checked the 1889-91 Century Dictionary to see if it had an account of the name of the Bird of Paradise. I found almost the same account in the dictionary, reproduced below:

[I]t was called apode from the fable that it was always on the wing and had no feet, a notion which was strengthened by the fact that the specimens which used to reach naturalists were without feet, these having been removed in preparing the skins.

From The Century Dictionary’s Bird of Paradise definition

There are two differences in Century’s account. Firstly, Century does not tie the name “Bird of Paradise” to the legends around the magnificent bird lacking feet. Second, Mr. Bird of Paradise suggested that people thought that the Red Bird of Paradise had no wings. Century, conversely, suggests that people thought “that it was always on the wing.”

The Red Bird of Paradise Minds Its Appearance

Dr. George Bennett, a nineteenth century explorer, reported the following account of a captive Red Bird in Paradise:

I observed the bird, before eating a grasshopper, place the insect upon the perch, keep it firmly fixed by the claws, and, divesting it of the legs, wings, etc., devour it with the head always first.

George Bennett (quoted in Birds)

This is turning into the most graphic bird article since a certain unfortunate pecking incident described in the Mandarin Duck article. Dark stuff. I hope that children did not follow the Red Bird of Paradise’s example in handling grasshoppers. That is how serial killers and genocidal despots are made. But I digress. There is a point to the story beyond gratuitous bird-on-grasshopper violence. Dr. Bennett continued:

It rarely alights upon the ground, and so proud is the creature of its elegant dress that it never permits a soil to remain upon it, frequently spreading out its wings and feathers, regarding its splendid self in every direction.

George Bennett (quoted in Birds)

Dr. Bennett made the Red Bird of Paradise sound a touch vain, but having seen its feathers, I blame it not. I must make an additional note that “rarely alights upon the ground” is a very elegant description. Well done, Dr. Bennett – at least with regard to the second half of the quote.

When the Red Bird of Paradise Cries

The Birds editors inform readers that the Red Bird of Paradise utters “very peculiar” sounds. These sounds “resemble[] somewhat the cawing of the raven, but change gradually to a varied scale in musical gradations, like he, hi, ho, how!” When the Red Bird of Paradise raises his voice, he can “send[] forth notes of such power as to be heard at a long distance.” The loud projections of the Red Bird of Paradise, we are told, “are whack, whack, uttered in a barking tone, the last being a low note in conclusion.” When the Red Bird of Paradise prowls the trees for unfortunate insects, he wisely is quieter, uttering “a soft clucking note.”

As vivid as the foregoing descriptions of the Red Bird of Paradise’s cry are, there is no substitute for the real thing. While young readers in 1897 had little hope of hearing the Red Bird of Paradise cry, we are far more lucky today. Cornell University’s e-Bird site hosts 14 recordings of the Red Bird of Paradise for you to enjoy in the comfort of your own home.

How Does the Red Bird of Paradise Spend Its Days?

Above, we learned about the Red Bird of Paradise’s “soft clucking note” while hunting in the trees. What else does it do in the trees? “During the entire day he flies incessantly from one tree to another, perching but a few moments, and concealing himself among the foliage at the least suspicion of danger.”

In view of his gaudy plumage and the prevalence in 1897 of arrow-wielding hunters, he must do so with great skill. Indeed, National Geographic observes that the male Bird of Paradise’s beauty is impractical for everything but winning the attention of a mate. “Excessively long tail feathers might be great for attracting mates, but they aren’t exactly useful for survival.” This might be news to our friend the Resplendent Trogon. Fortunately for contemporary Birds of Paradise, National Geographic adds that do not have many natural predators, so they were able to focus on courtship instead of stealth. This paints a less perilous impression than some of the stories from 1897.

Extra Notes on Mating Rituals

Birds magazine does not discuss the Red Bird of Paradise’s mating dances much, despite Mr. Red Bird of Paradise’s having teased the subject. So, before continuing to the conclusion of the essay of the editors, I thought that it would be appropriate to turn again to National Geographic again for a short description of how male Birds of Paradise attract their mates. Note that the National Geographic content refers to Birds of Paradise generally.

National Geographic suggests that the dance moves of the male Bird of Paradise “may appear erratic.” However, “they are carefully choreographed to convince females that he is the best mate.” The male Bird of Paradise gauges his audience and works “tirelessly” to refine his moves until the female Bird of Paradise accepts him. While National Geographic notes that female Birds of Paradise look more subdued than the males, it adds that the females are in charge during the courtship, selecting their preferred mates.

Content from George Bennett’s “Wanderings in New South Wales”

The editors returned to Dr. George Bennett for some excerpts about the Red Bird of Paradise from his book “Wanderings in New South Wales.” Below, I will reprint the Bennett excerpt in its entirety:

This elegant bird has a light, playful, and graceful manner, with an arch and impudent look, dances about when a visitor approaches the cage, and seems delighted at being made an object of admiration. It bathes twice daily, and after performing its ablutions throws its delicate feathers up nearly over its head, the quills of which have a peculiar structure, enabling the bird to effect this object. To watch this bird make its toilet is one of the most interesting sights of nature; the vanity which inspires its every movement, the rapturous delight with which it views its enchanting self, its arch look when demanding the spectator’s admiration, are all pardonable in a delicate creature so richly embellished, so neat and cleanly, so fastidious in its tastes, so scrupulously exact in its observances, and so winning in all its ways.

George Bennett in “Wanderings in New South Wales” – Quoted by Birds

It is easy to see why Birds included multiple excerpts from Bennett. His prose in first faulting the Red Bird of Paradise for its vanity, but then pardoning it is clever and witty. “[A] delicate creature so richly embellished, so neat and cleanly, so fastidious in its tastes, so scrupulously exact in its observances, and so winning in all its ways.” I suppose any creature with such a long list of endearing qualities can be excused for being a bit full of itself.

An Unnamed Traveler’s Take

The editors included its treatise on the Red Bird of Paradise with the account of an unnamed traveler in New Guinea. The traveler was enchanted by the bird, and his description is enchanting in and of itself:

As we were drawing near a small grove of teak-trees, our eyes were dazzled with a sight more beautiful than any I had yet beheld. It was that of a Bird of Paradise moving through the bright light of the morning sun. I now saw that the birds must be seen alive in their native forests, in order to fully comprehend the poetic beauty of the words Birds of Paradise. They seem the inhabitants of a fairer world than ours, things that have wandered in some way from their home and found the earth to show us something of the beauty of worlds beyond.

An unnamed traveler on the Red Bird of Paradise, quoted in Birds

Concluding in Paradise

The Bird of Paradise content included the two best-written external accounts in the magazine so far. The excerpts from Bennett’s Wanderings and the unnamed traveler’s account were remarkably well-written and memorable. The magazine not only taught children about birds, but also about enjoying good writing.

To be sure, the Red Bird of Paradise content brought back some of the avian violence from earlier chapters. However, in this case, the avian violence was at least relevant to the story in that it tied into how the Red Bird of Paradise was seen by people and had earned its name.

The content was a bit short on some things about the Red Bird of Paradise, namely its mating rituals, but we were able to fill in the gaps with contemporary resources.

The Red Bird of Paradise continued our pretty bird series admirably, and I hope that you enjoyed learning about it as much as I did. The Red Bird of Paradise now takes leave to admire himself. Our next entry in the series will cover a variety of bird that many of us will be somewhat familiar with. I hope you join us for the Yellow Throated Toucan, coming soon.