I build guitars in addition to being a musician. For my recent project, I constructed a unique nine-string guitar as a tribute to blues legend Big Joe Williams and his iconic nine-string guitar. My new nine string was painted by the talented Andy Finkle.

In this post, I will discuss my journey to building the Joe Williams-tribute nine-string guitar and the life of Williams.

Discovering Big Joe Williams Through Insomnia

I often learn things by watching videos while suffering from insomnia. While I was struggling to sleep one night about seven years ago, I played a video titled “American Folk Blues Festivals 1963 1966 The British Tours.” I had almost finally fallen asleep when I heard the announcer in the video say the following:

I’d like to bring you a gentleman who plays a nine string guitar, the only man in the world who plays a nine string guitar, the only man in the world who has a nine string guitar: Big Joe Williams.

I was suddenly wide awake and my interest was piqued. Williams took the stage and I was captivated by his performance. He performed the traditional Blues song, Baby Please Don’t Go. While I knew about the song, I had not been aware that Williams was responsible for arranging and popularizing it. I was mesmerized by the strange hollow sound that Williams’ guitar produced. His electrified acoustic guitar was covered in tape, and it had a strip with three tuning pegs jammed through the top of the head stock.

I immediately began researching Big Joe Williams, both to learn more about him and to learn about his unique instrument in the hope that I could replicate the design.

Who Was Big Joe Williams?

Joseph Lee Williams was born on October 16, 1903, in Mississippi. He rose to prominence as a blues musician in the 1930s and signed with Bluebird Records in 1935. I had been familiar with two of the songs that Williams popularized – Baby, Please Don’t Go and Crawlin’ King Snake – before I knew about Williams himself.

Williams died on December 17, 1982, after a long and distinguished career. His epitaph fittingly reads “King Of The Nine String Guitar.”

Big Joe Williams and Bob Dylan

My main musical interest is in the music and songwriting of Bob Dylan. While researching Big Joe Williams, I learned that he had a significant impact on Dylan.

According to an interview with Libby Rae Watson, Bob Dylan encountered Williams in Chicago. Williams referred to Dylan, who would sit at his feet and watch him play, as “Little Bobby.” Dylan picked up Williams’ technique of “double thumping his thumb on the guitar” and Williams encouraged Dylan to perform traditional blues songs.

Dylan and Williams played together in the early 1960s – billed as “Big Joe Williams and Little Joe.” Dylan played the harmonica and sang backup on Williams’ recording of Sittin’ On Top Of The World. In a poem that Dylan recited in 1963, he stated that he had too many influences to list them all, but went on to name just two: Woody Guthrie and Big Joe Williams.

On Big Joe Williams’ Unique 9 String Guitar

Many things went into making Big Joe Williams a unique musician. One of those was the instrument with which he was associated – the 9 string guitar.

A standard guitar has only six strings. These strings are tuned in “standard tuning” – which runs (from the lowest and thickest string to the highest and thinnest string):

E | A | D | G | B | E

Williams generally played in a tuning called “Open G” – which means that the guitar strummed open is a G cord. This means that his tuning (from thickest to thinnest) went:

D | G | D | G | B | D

Williams’ extra strings did not add extra notes like we see with modern electric guitars with extra strings, traditional Russian guitars, or antique harp guitars. Instead, Williams used the extra strings to double the strings. Unlike traditional 12 string guitars, where the doubled strings are tuned to octaves – meaning the second string in each pair is higher than the first string, but the strings are the same note – Williams tuned his doubled strings in unison. He doubled the 4th, 2nd, and 1st strings only. See the result below:

D | G | DD | G | BB | DD

Big Joe Williams always performed with the capo on the second fret, meaning that his guitar was tuned to an open A chord. He likely set his guitar up in this way for two reasons. Firstly, his set-up fit his voice. Secondly, this set-up made made it possible for Williams to hold the strings in place since he modified his guitars on his own and not professionally. There is a legend that Williams came up with his unusual guitar configuration to keep his friends, who were prone to touching his guitar, from being able to play it. While this is a fun story, it minimizes the science behind Williams’ set-up. He was a master at using the doubled strings for side licks and his control over the volume knob on the electric guitar pickup was impressive.

Williams sometimes employed even more unusual modifications:

When I saw him playing at Mike Bloomfield’s “blues night” at the Fickle Pickle, Williams was playing an electric nine-string guitar through a small ramshackle amp with a pie plate nailed to it and a beer can dangling against that. When he played, everything rattled but Big Joe himself. The total effect of this incredible apparatus produced the most buzzing, sizzling, African-sounding music I have ever heard.

Sounds Good to Me: The Bluesman’s Story, Virginia Piedmont Blues (Original)

My Quest to Build a Nine String Guitar

I sought to build my own version of Big Joe Williams’ iconic nine string guitar. However, there were challenges that I had to untangle. Williams modified arch top guitars and flat top guitars that had tailpieces (where the strings come from a metal retainer anchored to the base of the guitar) and floating bridges (removable wooden saddles where the strings sit).

The Challenges

I only build solid body electric guitars. Moreover, I wanted to come up with a more stable version of Williams’ modifications in order that my guitar would not need a capo to hold the strings in place. I knew that this would be a difficult project because I have no experience working with metal. For that reason, all of my components would either need to have been modified from pre-existing parts or I would need to commission the parts.

Initial Attempts

I experimented with several different methods to recreate Big Joe Williams’ iconic nine string guitar.

One idea I had was to drill through a traditional telecaster-style bridge and add an extra three strings that ran through the body. I also tried modifying an old Teisco-style tremolo system that had long-since lost its arm and ability to bend notes. For the latter idea, I used a wooden bridge and a string retainer by the head stock to put the extra strings in place. In so doing, I quickly discovered that modifying a pre-existing nut was difficult because I had to teach myself to carve the nuts and slot them from scratch, which I had never done before. This was, however, the only way to obtain string spacing that was both uniform and comfortable.

My initial efforts yielded two prototypes. One is now in the hands of Ronnie Wheeler, a blues and rock artist, while the other is part of a private collection.

Refining the Process

As I continued working on my nine string guitar methods, I discovered that many telecaster bridges are made with the option of stringing the strings through either the bridge or the body. This allowed me to set up the three unison strings directly through the top while I set the standard six strings through the body. In order to save myself from the trouble of having to add a notch and telecaster saddles, I went with vintage-style “threaded” saddles, which are covered with notches like a screw, allowing me to conveniently space the strings out without too much work. I also decided to place the three extra tuners on the right side of an almost-Fender-style headstock, while leaving the other six on the left, because the three tuners through the top were difficult to manage.

After deciding on my methodology, I set out to make my own stage-ready nine string guitars. I began building the one that I am detailing here at the same time I made a sibling guitar for Mark Caserta, a fellow-Brooklyn musician with whom I regularly collaborate. However, Mark’s guitar is a bit different than mine. I modified a twelve-string-style bridge for him with individually adjustable saddles. This set-up allows for more control in intonation. For my guitar, I stuck with the traditional Telecaster configuration, which I have been working with for the majority of my experiments.

Working With Andy Finkle

My Mother discovered Andy Finkle, a talented artist, on Instagram. I am not sure how she did, but she began periodically sending his posts to me. Andy’s work is wonderful. He usually depicts “cryptids” – which are animals and creatures derived from folklore such as Big Foot and Moth Man. My Mother first fell in love with his work when she came across a piece that depicts what appears to be a skinny alien – which she thought resembled a photograph of my Father when they were dating. I obtained the picture for her for Christmas one year, and in the process I began working with Andy.

Andy and I struck a deal. I constructed a baritone electric guitar for him. In return, he offered to paint a guitar body for me. I decided that I would use the guitar that he delivered to me for a nine string instrument.

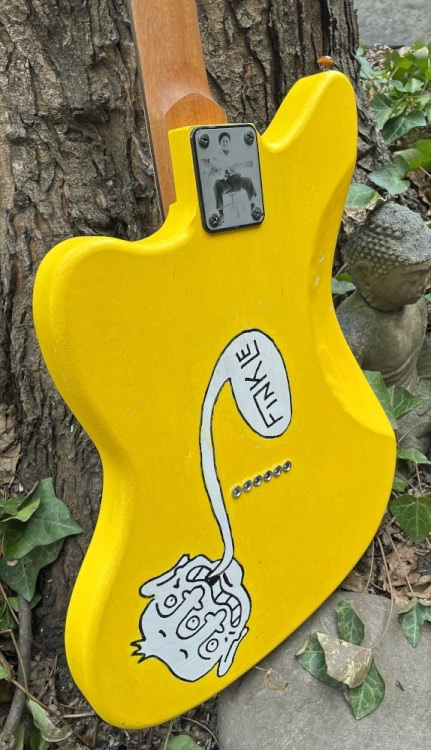

I sent Andy a “tele-master” style body, which is a cross between a Jazzmaster in shape and a Telecaster in configuration. Instead of asking him to paint something specific, I told him that he could paint it however he wanted. He responded that he would ”jam it full of Cryptids.” Andy delivered on his promise.

On the surface, Andy’s figures are charming and cartoon-like. However, there is a deeper, more sinister air to them, fully in tune with Cryptid lore. It is that depth that makes his work special. The guitar is absolutely wild and eye-catching, and I could not be more proud to have a piece of Andy’s work in my collection.

The Parts

I decided to go all-out on the components.

For the pickups, I contacted Rob Banta of Gemini Pickups to order a set of his coveted “Suprocaster” pickups. I sent him a picture of the guitar body and asked him to copy the colors in his work. For the bridge, I contacted Aldridge Empire and asked him to make a bridge to match the guitar aesthetic.

Instead of using the Fender-version saddles, I ordered a set of Glendale “Groovy 60s” cold-rolled steel-threaded saddles, which were an improvement because the threads are spaced out for the appropriate gauge of the string.

I decided to do something a bit weird for the electronics. Here, I reversed the traditional telecaster control plate so that the volume is closer to the guitarist’s hand than the selector switch. Instead of a tone knob, I added a 1950s telephone on/off switch that I had purchased at an estate sale.

This allows me to mute the guitar as well as to attempt volume control just like Big Joe Williams himself. I threw a Sperzel “Drop D Thing” on the headstock, which allows me to quickly drop my lowest string a full step and back up if I so choose.

Finally – in the realm of aesthetics – I had an image of Big Joe Williams laser-etched on the neck plate as a tribute to the legend who inspired the project.

Final Thoughts

The build was a success. I did my best to make the guitar’s configuration as interesting as Andy’s art – and I only hope that I did it justice. The Gemini Pickups are unparalleled, and I am happy keeping this set that Banta constructed.

I do not normally play in Open G – I am more partial to Open D or standard tuning – and I have found guitar strings in both tunings.

The tone of the guitar lies somewhere between a traditional six string and a twelve string. It is quite charming because it does not become overbearing with the octaves of the latter. Many folks are pleased with how it sounds, despite being confused by the unusual string count.

To hear the guitar in action, see me use it to play my original song, Ghost Woman Blues #2, along with Mark Caserta for the 2022 edition of NPR’s Tiny Desk Contest (video link). I published an article about Ghost Woman Blues #2 last October.

While I am happy with the progress that my project has made, I look forward to perfecting my nine string guitar builds for generations of guitars to come.