Flood of Tears is the English-language translation of a freeware Japanese visual novel called FLOOD OF TEARS. The translation was led by Mr. Seung Park of Insani. The original Japanese game was developed by TMS and released in Japan on October 30, 2001. The English translation was published on May 19, 2005, and submitted during the precursor phase to the 2006 al|together visual novel translation festival. Of the more than 30 freeware Japanese visual novel translations submitted to the 2005, 2006, and 2008 al|together festivals, FLOOD OF TEARS is the second oldest Japanese game, having been published just three months after Plain Song, which I reviewed in December 2022. I am currently in the midst of a project to review nearly all of the al|together translations. Below, I submit my review of Flood of Tears as the 18th entry in the series (see completed reviews).

Flood of Tears is played through the perspective of Tarou Yamada, an ordinary middle school student with a penchant for comedy. He spends most of his time at school, and after school, bantering with his best friend and classmate, Hina Kawase, who plays the role of straight woman in his skits. Early in the game, Tarou also takes an interest in a mysterious, taciturn transfer student named Umi Shinoyama, feeling as if he had some previous connection to her despite having apparently never met her before. Through it all, Tarou must deal with his strange teacher, Yazawa the Shark, who uses Tarou as a sounding board for the manly adventures that make up Yazawa the Shark’s failed love life.

Looming over Tarou’s idyllic school days are his haunting dreams, one of which serves as the first scene of Flood of Tears.

But if that as the case, why were all these tears freezing where they stood?

Quote from opening scene of Flood of Tears

The specter of something dark is never too far from the forefront of Flood of Tears, and the overarching plot reveals itself in the game’s second half.

Flood of Tears is an interactive visual novel, featuring a total of two routes with distinct endings along with several dead ends. It is also one of the longer al|together visual novels, albeit still short by the standards of commercial visual novels.

With our brief introduction aside, let us turn to the review of the uneven, but ultimately surprisingly good, Flood of Tears.

Flood of Tears Details

English version

| Title | Flood of Tears |

| Translator | Seung Park (Insani) |

| Release Date | May 19, 2006 |

| Engine | ONScripter-EN |

| Official Websites | Insani; al|together 06 |

| Visual Novel Database | VNDB Page |

Original Japanese game

| Title | FLOOD OF TEARS |

| Developer | TMS (staff page) |

| Original release date | October 30, 2001 |

| Engine | NScripter |

| Archived Website | Prerelease and Final Capture |

Running and downloading Flood of Tears

Flood of Tears is available as a torrent download from the Insani website for Windows, MacOS, and Linux and as a direct download for Windows from Kaisernet. Note that the direct download links on the mirrored al|together 2006 site do not work in this case. However, it is also available in all versions as a direct download from a curated al|together collection on MEGA.

- Insani (Official torrents)

- Kaisernet (Windows direct)

- MEGA collection (direct)

It took me a couple of weeks to download the Windows torrent when I first tried in 2020. However, the state of the al|together torrents is significantly healthier now than it was in 2020. For those who are able, I recommend downloading a torrent for Flood of Tears and seeding it to help ensure that the official source remains accessible to all. But note the direct download options if you are either unable to download the torrent or want to read the novel as soon as possible.

Flood of Tears is written in ONScripter-EN, so the three guides that I have previously published for ONScripter-EN games apply. See my instructions for running them locally on Linux (from installed ONScripter-EN or from binary in directory) and for extracting the content of Windows ONScripter-EN .exe files and running them locally on other systems.

All of my tests of Flood of Tears have been done on Linux. My review is based on running it natively on Linux after extracting the contents of the Windows game into a directory and running the ONScripter-EN Linux build in that directory. However, I also tested the Windows version on Linux under WINE back in 2020, playing through one of the game’s two routes, and encountered no issues. Windows users who do have issues may consider trying a newer version of the ONScripter-EN executable (see my directions for doing so on Linux, the same principle would apply on Windows).

General overview of Flood of Tears

Flood of Tears is difficult to summarize in general, and it is even more difficult to summarize without spoilers. This review is free of meaningful spoilers, so I must tread carefully in offering a general overview.

Insani, the team behind the Flood of Tears translation, provided the following synopsis:

An annoying protagonist, an ordinary school life, a few friends here and there. This is the story of a young man who falls in love willingly, and perhaps of a couple young women who fall in love somewhat less willingly.

Insani

The synopsis is not inaccurate, but I fear that it may confuse prospective readers.

The “annoying protagonist” is Tarou Yamada. While the ages of the cast are not expressly noted in the game, Tarou and his classmates appear to be junior high school students. As I noted in the article introduction, Tarou is a funny guy who likes to make jokes while slacking off.

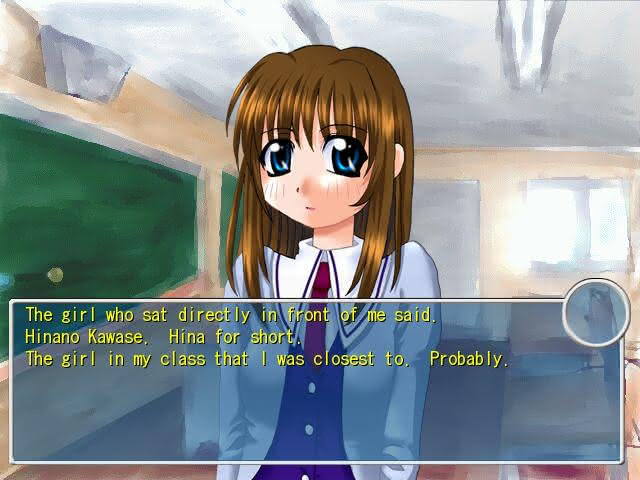

He lavishes most of his attention on his next-desk neighbor and best friend, Hina Kawase. For her part, Hina often expresses exasperation with Tarou’s antics, but she always plays along and serves as the perfect straight woman for his comedy routines.

Is Tarou annoying? I personally liked him and thought he was one of the better protagonists of the entire al|together visual novel collection, but even so he comes off better on the Hina Kawase route than he does in the Umi Shinoyama route. Mileage may vary regardless.

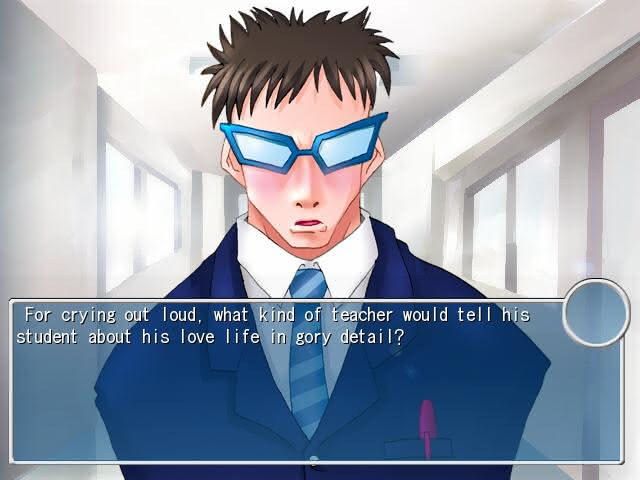

The third main character is Umi Shinoyama. Umi is a transfer student of few words – stoic, taciturn, and without friends. She first catches Tarou’s attention early in the story when she gets him out of an annoying situation with his teacher, Yazawa the Shark (Yazawa exists almost entirely for comic relief) and again later when Tarou bumps into her while running to school.

Moreover, Tarou has a strange feeling that he has some earlier connection to Umi, something that the story does not do much to dissuade the reader from believing. Umi is initially actively standoffish toward Tarou, but with enough persistence (this is arguably Tarou’s “annoying” route), he begins to break through.

Insani’s preview foreshadows the fact that Flood of Tears is a love story. Moreover, its set-up with Hina and Umi betrays that it is a branching love story with different routes resulting from the player’s choices. I understand what Insani meant when it wrote “young women who fall in love somewhat less willingly [than Tarou],” and the preview is generally accurate in one of the two cases, but I will note without spoilers that the less willingly pertains to the overall circumstances of the story rather than to Tarou’s conduct.

Insani’s synopsis includes an interesting assessment that would have, at the time of its publication, helped place the game in the context of popular visual novels of the day:

With plot structure and progression very similar to – and some might even say in homage to – works like Kanon and SNOW, this piece will most likely feel immediately familiar to most readers.

Insani

I am not familiar with SNOW, but I am familiar with Kanon (based on its second anime adaptation in 2006-2007 by Kyoto Animation rather than the original visual novel). Kanon is a branching romance story full of tragedy and magical realism elements. I am a fan of the anime, and having seen that reference before reading the Flood of Tears synopsis, I was already intrigued. Flood of Tears makes little secret of the fact that it has tragic elements – its haunting opening scene which nearly drops the game’s title and makes it clear that Tarou’s happy-go-lucky days with Hina (or Umi on the Umi route) may not be numbered.

(Note: While Kanon and SNOW were both originally released as adult visual novels, Flood of Tears is fully appropriate for all ages.)

Flood of Tears Review

Below, I review Flood of Tears in several sections, beginning with a technical overview of the game’s structure, then looking at its aesthetics, and finally concluding with an assessment of the story and the novel as a whole.

Estimated reading time

Flood of Tears is one of the longer al|together visual novels. One Visual Novel Database reader reported 2 hours and 51 minutes for completing both of the game’s routes and several of its bad endings. Estimating the precise amount of time it takes to read Flood of Tears depends in part on how one reads, makes use of save points, and figures out the choices to get to the true endings. I suppose that 2 hours and 51 minutes may be right for some, but I will venture that it can be done by most readers in less time if one makes “correct” choices and skips a few sections of duplicate text on a second play-through.

Both Hina’s and Umi’s routes are similar in length, although I think (without having done the full word count assessment) that Hina’s is probably slightly longer.

Game-play and structure

Flood of Tears is one of the most interactive visual novels of the al|together collection. Playing to the end of Hina’s or Umi’s route requires nine choices. Three choices are unique to each route while six are shared, meaning that Flood of Tears has 12 choices in total.

The first six choices make up what I will describe as the game’s common route. No matter what the player has Tarou do, he will always be confronted with the same six choices on the common route. Depending on how Tarou handles these choices, there are three possible outcomes at the conclusion of the common route: (1) Player enters Hina route; (2) Player enters Umi route; or (3) Bad ending.

The first bad ending is the result of not accruing enough points with either Hina or Umi needed to enter their respective routes. Most, but not all, of the first six choices present a clear choice between spending time with Hina or spending time with Umi. While it is not necessarily the case that the player must choose Hina on every occasion for her route or Umi on every occasion for her route, some of the choices are mandatory for each. To use a non-specific example, of the first two Hina vs Umi choices, choosing Hina on one is mandatory for having access to her route while the second is optional, provided that the player chooses to spend time with Hina in the other instances. All of the Hina vs Umi choices are clear and obvious, so players should have no difficulty sticking to the path that leads to one of their routes. There is one choice between spending time with one of the girls or not spending time with that girl, but it is foreshadowed enough that it too should be fairly obvious.

(For those interested in experimenting, the game uses a formula to determine whether the player has enough points (for lack of a better term) to get on Hina’s or Umi’s route. You can see the game’s code in the 0.txt file in its directory, but make sure not to alter it for obvious reasons.)

Flood of Tears splits after the common route. Provided the player avoids the indecisive bad end, there is a Hina route and an Umi route. Both of these routes have three choices. Five of the six choices are of the “survive and advance” flavor, meaning that the correct choice continues the story while the wrong choice leads to a bad ending. These choices are not difficult, but they are less obvious than the common route choices. We previously looked at similar uses of the survive and advance structure in reviews of Plain Song and Wanderers in the Sky (not to mention literal cases in Night of the Forget-Me-Nots and a commercial visual novel called Bad End).

One structural note to be aware of is that Flood of Tears does not allow the player to save on choices. Some of the visual novels we have looked at actually allow you to create a save point on a choice, which makes it easy to re-do the choice (see a notable commercial example in my review of ACE Academy). However, Flood of Tears blocks saving on choices, meaning that it is generally wise to create save points at the start of each new day (the game’s events are generally broken into days, starting with Tarou waking up in the morning).

There is a menu option to skip to the next choice, making these save points valuable even if they are not made right next to a choice.

Visuals

While many of the games built with NScripter (the Japanese engine behind most, but not all, of the al|together visual novels) look similar, Flood of Tears is unique in many respects, including its art style and text box. Flood of Tears’ aesthetic may be an acquired taste, but you can judge for yourself from my assessment, supported by screenshots.

(Note that the art was by EMU, and we here at The New Leaf Journal are fans of emus.)

Characters

Only four characters have portraits in Flood of Tears: Hina, Umi, Yazawa the Shark, and Tarou’s mother.

Despite Yazawa being described by Tarou (to Hina’s confusion) as the mascot of Flood of Tears and being the subject of the game’s shortcut icon, Hina was featured on the website and promotional materials and is, in my opinion, the principal main character as well as the first to appear on screen. So let us begin with her.

The Kanon similarities noted by Insani are immediately clear in Hina’s design: The huge eyes and the near lack of nose. The character design style is a bit dated, but I am in favor of Hina’s design as a general matter. It is well-conceived and captures her terrific personality, which I will describe later.

However, one flaw in the character designs in Flood of Tears is a lack of variety.

Each character has only one pose and a fairly limited set of expressions. Hina only has four expressions, and one is of a bit lower quality than the first three.

Another minor knock on Hina and variety is that she has no smiling expression, despite being described as smiling on (very rare) occasions. Her neutral and annoyed expressions work well for most purposes since she is often responding to some absurd thing that Tarou said, either willingly or somewhat willingly playing along with his skit.

But she should have an extra expression. Moreover, there is one scene wherein Hina should have a non-school uniform outfit.

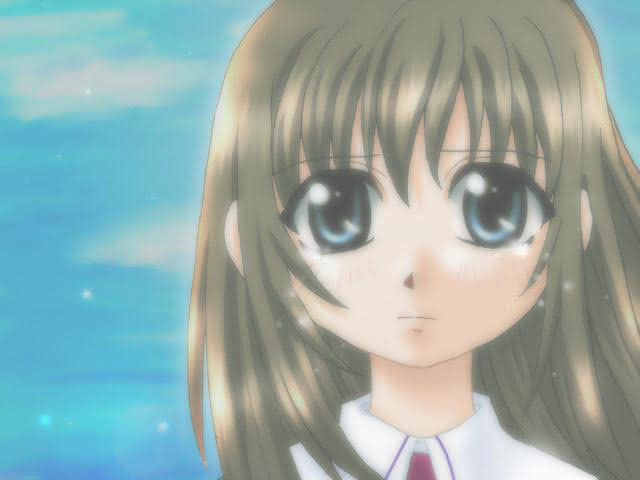

Next we have Umi.

Umi pretty much has a single expression, but unlike Hina, she does receive a non-school outfit.

I personally found Umi’s portrait a bit bland – it lacks the charm and character of Hina’s. While Umi shows a narrower range of emotions and reactions than does Hina, she could have still benefited from a few extra portraits.

Both Hina and Umi receive three CG scenes, including one for each at the end of their routes. (Note: One of Hina’s CG scenes is more of a hybrid between a normal scene and a CG scene, but I will count it anyway.)

Hina’s set of CG scenes are quite good in a thematic sense. Umi’s marked a step up in animation quality but left less of an impression.

Yazawa the Shark is a comic relief character and never plays a significant role in the story. His character design is certainly distinctive – I wonder if the developer had a teacher like him at some point.

Tarou’s mother plays a significant role in the latter stages of one of the two routes, but she otherwise exists for some minor comic relief. She only has a single portrait.

She could have used an annoyed expression, but her default is sufficient for her limited appearances. (Surprisingly, Tarou usually is the one with better grounds to be annoyed in their interactions.)

Backgrounds

After praising the previous novel I reviewed, A Winter’s Tale, for its large number of backgrounds, I will fault Flood of Tears slightly for having too few backgrounds given its length, even taking into account that most of the story takes place in just a few locations. Notably, it used the school hallway for everything that happened in Hina’s and Tarou’s school that was not in the classroom – including school festival events, and we were notably missing a distinct background for the shopping district and movie theater, both of which pop up at points during the game.

The background art style is perhaps more distinct than the character designs – and it may be another “for better or worse” situation. When I see the art, I think of Cray-Pas (did anyone else use those in school)? It very much looks like it was drawn in Cray-Pas.

Mixed in with the Cray-Pas backgrounds are a few more conventional sky and snow backgrounds.

One thing I will give Flood of Tears credit for is how it handles lighting. For example, the classroom (probably the most common location), road to and from school, school roof, and playground all have variations for different times of day.

The sky backgrounds (especially one sunset scene) and the classroom are the best of the bunch. On the whole, while the quality is mixed, I did genuinely like that Flood of Tears has a unique style that did not make me feel like I was looking at something I have seen in many al|together novels.

My main qualm is with the number of locations without specific backgrounds.

UI elements

Many NScripter visual novels had text run from the top of the page to the bottom, overlaying characters and backgrounds. However, we have also reviewed a number of NScripter/ONScripter-EN games that use text boxes, and Flood of Tears falls into the text box camp. This is fine by me – I prefer text boxes.

Flood of Tears’ text box is unique. It takes up about 1/3 of the screen and is semi-transparent-blue, allowing us see the background and character underneath.

There is also a circle on the top right of the text box. I am not sure why, but I suppose it adds some style.

The text is generally easy to read against the translucent blue background, but there are a few instances where Flood of Tears would probably run afoul of contemporary accessibility best practices.

When reading through text history, the text is rendered in yellow – which is generally easier to read than the default white.

Music

I counted about six background tracks in Flood of Tears, which is a bit underwhelming given its length. However, all of the tracks fell firmly in the “pleasant enough” category, giving the game a distinct ambiance without ever being overbearing or getting in the way. Despite the small number of tracks, I did not find them repetitive. I did note on the archived version of the official website that TMS once offered remixed versions of the tracks for download, but I was unfortunately unable to find a working download link.

Translation Quality

I preface my notes on translation quality by noting that I have not only not played the original FLOOD OF TEARS, but I also cannot read Japanese. Thus, I am assessing the translation in terms of (1) how it reads in English and (2) obvious discretionary translation choices.

I praised the previous game I reviewed, A Winter’s Tale, for a translation that read flawlessly in English. Flood of Tears reads very well, and I dare say that from the perspective of an English-only reader, it appears to be one of the finest achievements of the al|together translations. This should be no surprise in light of the fact that it was produced by Insani’s lead translator, Mr. Seung Park.

While I will delve more into it in the next section, the highlight of Flood of Tears are the interactions between Tarou and Hina. Most of their conversations until the latter stages of Hina’s route consist of friendly banter. The translation, which comes without any obvious or glaring flaws, does a superlative job of conveying their charming and funny interactions in English.

Tarou is endearing in his ridiculousness, and the script did well to have him occasionally indulge in grandiloquence as he tries to salvage his newest theory or story.

Hina plays off Tarou perfectly, falling for his bait before deftly playing the straight woman or threatening Tarou when he goes too far into his own world.

Hina’s writing shows range – the scenes where she takes the lead in making Tarou march to the beat of her drum are among the game’s best. Tarou and Hina were quite entertaining, and that was only possible with a script that reads well in English.

Tarou’s and Umi’s conversations do not flow like Tarou’s and Hina’s due to the fact that Umi says very little, even in the late stages of the game. The translation effectively conveys her stiffness and formality, which obviously serve as means to keep Tarou at a distance.

The early game reveal what struck me as a few decisions to Americanize references that might have otherwise been unintelligible to ordinary English readers.

Were Dave Chappelle and Eddie Izzard popular in Japan? I have my doubts, but I have no issue with the choice – the point of the scene was for Tarou to establish that he looked for inspiration to comedians in coming up with strange things to get reactions from Hina. The translation conveys this effectively. (I will add that the reference aged well too.)

Also notable: The game preserves honorifics. That Tarou uses Hina’s first name is notable..

Writing and story quality

Flood of Tears is a difficult visual novel to pin down, especially without discussing spoilers in detail. Before I offer my own assessment, I quote from Insani’s:

[Flood of Tears] possesses immense heart, which is why at the end of the day we, the translators, could only say a warm ‘thank you’ and turn a blind eye to what flaws it had.

Insani

Flood of Tears does have immense heart, and it also has some difficult-to-avoid flaws. It has a particular strength that largely overcomes the flaws and, in my assessment (based on some scores of videos I have seen in the Visual Novel Database), it deserves recognition for what it does well.

Flood of Tears has some significant similarities to another al|together 2006 submission that I reviewed, Shooting Star Hill. In Shooting Star Hill, the protagonist took a distinct interest in a shy, lonely girl named Kana Moriyama. Its set-up has marked surface similarities to Umi’s story in Flood of Tears, but what makes me think of the stories together is how they mix a down-to-Earth human story with extra elements. Shooting Star Hill spoke often of aliens. As one may infer from Insani comparing Flood of Tears to Kanon, it has its own set of unnatural elements.

One interesting thing about Shooting Star Hill was that it was possible to understand the novel’s message while interpreting all of its supernatural elements metaphorically. That is not quite the case with Flood of Tears. While Flood of Tears presents a human story – especially in the case of the Hina-Kawase route – its magical elements, foreshadowed by Tarou’s dreams, are more closely tied to the core of the story than were similar elements in Shooting Star Hill.

Before examining the overarching plot, let us look at the two main routes.

Flood of Tears’ strength comes in the character of Hina Kawase and her overall story arc. Hina is by all accounts a normal girl, but she is one of the most charming and best-written characters of the al|together collection (she holds her own compared to popular characters from commercial visual novels as well).

Tarou and Hina have a genuine rapport that comes through in their dialogue, and Hina’s reactions – from irritation to witty retorts – are always just right.

As I noted earlier in the review, Hina holds up well when she drags Tarou along with her own whims. Hina is fundamentally the sort of fictional character one could imagine being a good friend.

That Hina is charming, especially with Tarou, is critical to the latter stages of her route landing its emotional and thematic punch. It is only because Hina is likable and Tarou and Hina go as well together as they do that the final stages of their story, even with Flood of Tears’ unanswered questions, ultimately works.

While both Hina’s and Umi’s routes tie into Flood of Tears’ overarching story, Umi’s is more closely intertwined.

I give Umi’s route credit for taking a conventional start – a quite, standoffish girl who the protagonist has to wear down with persistence – to some unexpected places. Umi’s character and motivations turned out to be far more complicated than I expected – although some of this is foreshadowed if the player goes through Hina’s route before Umi’s.

While Umi’s route is important to making sense of Flood of Tears’ world and scenario, and even to understanding the conclusion of Hina’s route, it suffers by comparison to the former. Tarou’s character works in Hina’s route because of how natural his interactions are. In the case of Umi’s route, Tarou is a bit pushy as he works hard to break through Umi’s shell. It is in the early stages of this route – before Tarou gradually succeeds – where I could see one finding him annoying. Moreover, the fact that getting on Umi’s route requires having Tarou flake out on Hina on a few occasions does somewhat undermine his likability.

Despite the fact that Umi’s circumstances are unexpectedly complicated, her route is ultimately less compelling than Hina’s on a human level.

The overarching story of Flood of Tears is the most difficult point to assess. While I am limited in what I can say without spoiling, the first scene of the game – which shows Tarou’s dream – depicts a traumatic event, which looms over the story. It ultimately ties into both Hina’s and Umi’s routes. Neither route does much to fully demystify the supernatural plot, but Umi’s route answers more questions. What Flood of Tears leaves unanswered hurts it more than Shooting Star Hill and its unanswered questions because of the centrality of the supernatural elements to where bout of Flood of Tears’s conclude. This game raises, but does not fully explore, interesting questions about looking back, looking forward, and living in the present. It feels a bit unfinished, albeit one of the endings was decisive for reasons I will not disclose here.

Flood of Tears may be a bit too ambitious for its own good, but what it did well – the Hina-Kawase route in its entirety – it did exceptionally well.

Miscellaneous technical points

There are two disappointing technical points for Flood of Tears.

Firstly, despite being a multi-path visual novel with two endings and several CG scenes, there is no extra content after completing the game. I expected to see a list of endings, a jukebox, or at least a CG gallery. Unfortunately there was nothing t at all.

Secondly, Flood of Tears only has nine save slots. This is too few save slots given the length of Flood of Tears* and the number of choices. It was the first visual novel of my 18 (counting Flood of Tears) al|together reviews wherein I ran out of save slots while trying to test different choices and paths.

On the plus-side, Flood of Tears’ “skip to choice” functionality is useful for quickly trying different choices without needing to wade through previously-read text.

Conclusion

Flood of Tears had grand ambitions that it did not fully realize, but it fully realized the story of Tarou and Hina. This was the heart of the script, and for presenting one of the most natural character relationships that one will find in a visual novel, Flood of Tears deserves praise despite its flaws.

It is easy to fixate on what could have been at the expense of appreciating what was.

The Umi route, while not the same quality of the Hina route, proved to be an interesting read in its own right, raising questions that Flood of Tears did not get around to fully answering.

Despite feeling a bit unfinished in some respects, Flood of Tears is an easy al|together visual novel to recommend. The Hina route is worth the (free) price of admission alone and the Umi route is solid so long as one does not get hung up on comparing it to the game’s better half. That Flood of Tears invites player engagement and offers a somewhat complicated choice structure in the common route (by the standards of the al|together collection) should make it more accessible to potential readers who are not keen on playing a visual novel that does not invite any player input.

I join Insani in offering a warm thank you to TMS for a job well-done, and I also extend a warm thank you to Insani for the excellent translation.