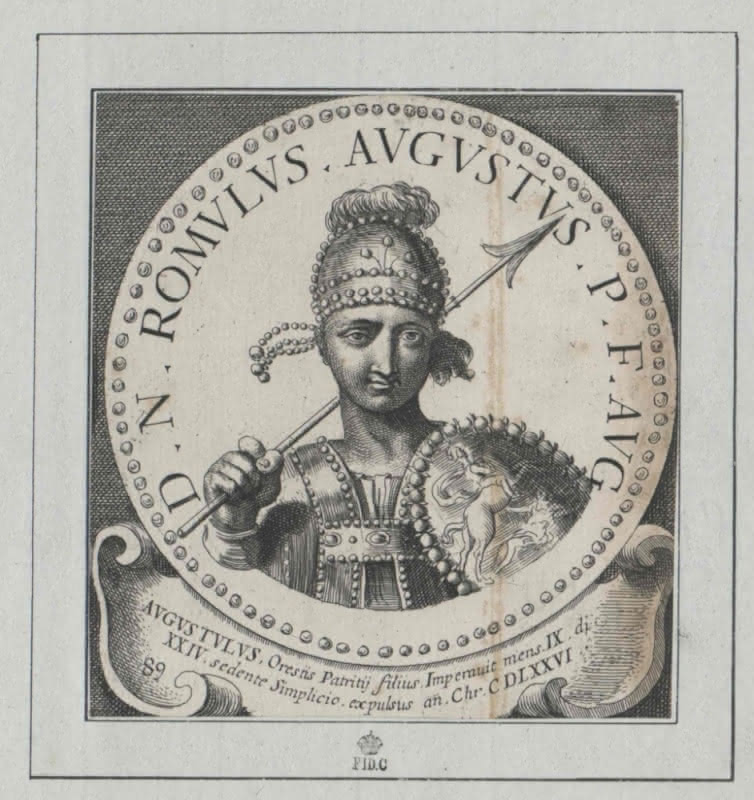

On September 4, 2020, I published an article commemorating the 1.544th anniversary of the “fall” of the Western Roman Empire. That post chronicles the last days of the Empire in the West in a brief overview. As I concluded, the Western Roman “Empire” did not “fall” so much as decay before transmogrifying. To be sure, there was little “Empire” left in the West in the decades preceding the capitulation of the boy-“emperor” Romulus Augustulus to the Germanic warlord, Odoacer. (The actual title of the last emperor was, of course, Romulus Augustus. “Augustulus” was a diminutive nickname.)

Having commemorated the 1,544th anniversary of the end of the Roman Empire in the West in 2020, I saw no reason to not similarly commemorate the 1,555th anniversary in 2021. For this year’s commemoration, I will focus on the life and times of Romulus Augustulus, who is traditionally considered to be the last Roman Emperor in the West. I will conduct my survey by studying all of the resources published to Project Gutenberg, making use of DuckDuckGo’s effective domain-specific search functionality.

As we found last year, and will find again, the sources on the “reign” of Romulus Augustulus and his post-“imperial” life are few, and those few sources are sometimes at conflict with one another. That the information about the dramatic personae of the final days of the Western Roman Empire is scarce is a symptom of the state of Rome at the end. Ultimately, deciding what became of Romulus Augustulus after his brief stint in the imperial purple is something of a choose-your-own-adventure endeavor.

- Revisiting Last Year’s Article

- Accounts of the Rise and Fall of Romulus Augustulus

- “General History of Rome: From the Foundation of the City to the Fall of Augustulus” by Charles Merivelle (1903)

- “The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” by Edward Gibbon (1782)

- “A Smaller History of Rome” by William Smith (1881)

- Procopius With an English Translation by H.B. Dewing

- “The Great Sieges of History” by William Robson (1856)

- “The Age of Justinian and Theodora” by William Gordon Holmes (1912)

- “A History of Germany” by Bayard Taylor (1882)

- “The Holy Roman Empire” by James Bryce (1871)

- Conclusion: A Modern Take

Revisiting Last Year’s Article

Before surveying sources about Romulus Augustulus, it will be useful to revisit the broader article that I wrote about the demise of Rome in the West last year.

On January 11, 395, the last Emperor of the unified Roman Empire, encompassing both Rome and Constantinople, died at the age of 48. Rather than pass the entire Empire to one of his young sons, he partitioned the Empire. The 17-18- year- old Arcadius became Emperor in the East, and the 10-year-old Honorius became Emperor in the West.

Honorius’s reign was long and plagued by military setbacks, internal discord, and the sack of Rome in 410. Honorious died in 425, and he was succeeded by the similarly feeble Valentinian III, who ruled until 455. The downhill slide of the Western Roman Empire accelerated after 455, save for a brief glimmer of hope in the four-year reign of Majorian (457-61), which was promptly snuffed out by a Germanic warlord named Ricimer. Ricimer installed a series of increasingly impotent puppet Emperors in the years following his murder of Majorian.

Meanwhile in 474 in the Eastern Roman Empire, the Emperor in Constantinople, Leo I, had sent Julius Nepos to Ravenna (which was the capital of the Western Roman Empire in 474) to depose the incumbent puppet Emperor and restore order to the West.

The Rise and Fall of Romulus Augustulus

Nepos worked hard but struggled to right the sinking ship that was the Roman Empire in the West. He appointed Flavius Orestes, who had once served in the court of Atilla the Hun, as his magister militum (“master of soldiers”). It did not take long for Orestes to take his soldiers and depose Julius Nepos, who fled before Orestes reached Ravenna.

Instead of naming himself Emperor, Orestes followed the example of Ricimer in naming another to the throne while he held the real power. However, while Ricimer had appointed adults to the purple, Flavius Orestes chose his young son, Romulus Augustulus – who nominally attained the imperial purple on October 31, 475. Romulus Augustulus is believed to have been somewhere between the ages of 6-14 when he became Emperor.

The boy-Emperor was not recognized in the East . where then-Emperor Leo II continued to acknowledge the exiled Julius Nepos. One of Ricimer’s generals, the Germanic Odoacer, had restless troops under his command. Odoacer’s troops wanted substantial land holdings in Italy. Orestes refused. Odoacer turned to arms, captured Ravenna, and murdered Orestes in August 476.

We know that Romulus Augustulus was compelled to abdicate on September 4, 476. In all extant accounts, Odoacer spared the life of the boy-emperor. The Roman Senate sent word to Zeno (the emperor in Constantinople), along with Romulus’s royal vestments, that the Roman world only needed one Emperor. Odoacer became King of Italy, and after Julius Nepos died in Dalmatia in 480, Zeno nominally became Emperor of East and West while Odoacer continued to rule Italy.

Accounts of the Rise and Fall of Romulus Augustulus

As I noted in the introduction, the purpose of this article is to collect book excepts about the short reign of Romulus Augustulus and what happened to him after he was deposed from Project Gutenberg. There are few sources about the life and reign of Romulus Augustulus. The sources on Project Gutenberg ultimately draw from those few sources – none of which are entirely reliable.

To be clear, this project is not intended to be a comprehensive study of the life and fate of Romulus Augustulus, nor is it intended to reach any conclusions on the matter. This is, more than anything, a curious exploration of what we can cobble together from the texts in Project Gutenberg’s collection (with two additional references). I may undertake a more serious study of the extant texts about the boy emperor in a future article.

“General History of Rome: From the Foundation of the City to the Fall of Augustulus” by Charles Merivelle (1903)

What better place to start the survey than a book with the boy-Emperor’s name in the title? Charles Merivelle was an English historian who lived from 1808-1893. His grand history of the Roman Empire was published posthumously in 1903. His book actually does not appear on Project Gutenberg – I found it on the Internet Archive. But since I quoted the pertinent passage in a section of last year’s article, an exception to the Project Gutenberg rule is warranted. You can follow along with the original text.

Merivelle on Augustulus

According to Merivelle, Romulus Augustulus – “[t]he child with whom the Western empire was destined to perish,” was six years of age when he nominally assumed the throne in 475. In reality, his age is unknown. Mr. Ralph W. Mathisen suggested that Augustulus may have been as old as 14. Wikipedia’s page for Romulus Augustulus settles on 10, while Britannica proposes no date of birth. I will note that six is on the low end of accounts of Augustulus’s age.

Merivelle reports that after Orestes put Odoacer to death, he spared Romulus Augustulus. He writes that Odoacer showed mercy to Odoacer’s son:

Paulus, a brother of Orestes, was likewise put to death, but the tender years of the infant emperor were spared, and he found a last tranquil retreat in the delicious villa of Lucullus, on the coast of Surrentum.

While nearly all of the accounts have Odoacer sparing Romulus Augustulus, there is variance on his ultimate fate. We will see some of the differences in the following texts.

“The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” by Edward Gibbon (1782)

Edward Gibbon devoted some time to describing the circumstances of Romulus Augustulus’s shallow rise and gentle fall in his magisterial Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.

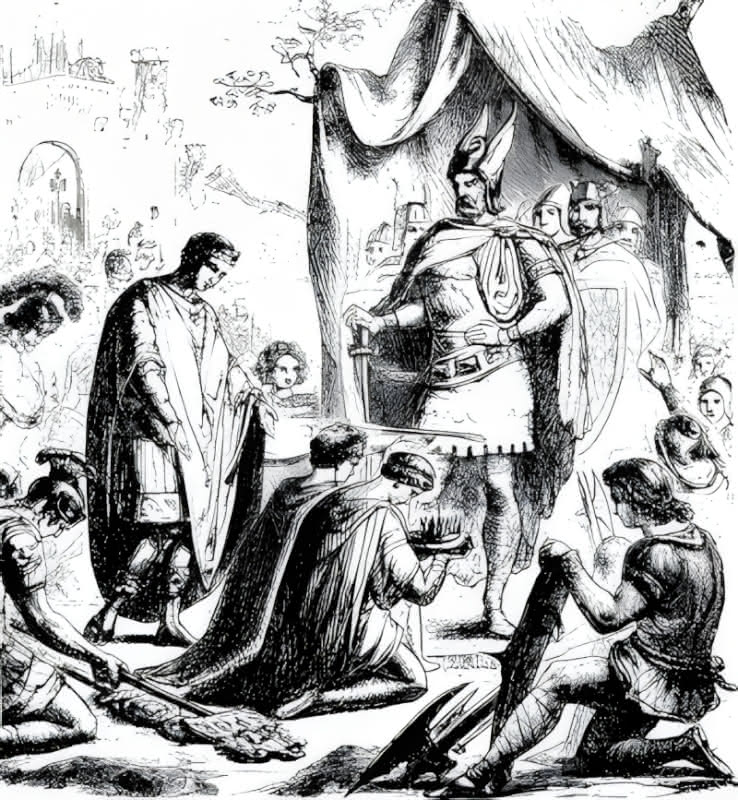

Gibbon wrote that after Orestes was executed, Romulus Augustulus was “helpless.” Without his father and Uncle (who was also killed), Augustulus “could no longer command respect.” In that condition, he “was reduced to implore the clemency” of Odoacer.

Gibbon wrote of Augustulus’s surrender:

The unfortunate Augustulus was made the instrument of his own disgrace: he signified his resignation to the senate; and that assembly, in their last act of obedience to a Roman prince, still affected the spirit of freedom, and the forms of the constitution.

Gibbon wrote about Augustulus’s life after his brief reign as Emperor in the most detail of all of our texts. According to Gibbon, Odoacer generously granted Augustulus clemency. Odoacer then dismissed the former emperor, along with the living members of his family, to the castle of Lucullus in Campania. The new King of Italy gave Augustulus an annual allowance of 6,000 pieces of gold.

Augustulus, according to Gibbon, lived out his days in Lucullus. Gibbon noted that in 488, the bones of St. Severninus were brought to Lucullus. Gibbon speculated that Augustulus was no more at that point. The castle was converted into a church and monastery in 500.

“A Smaller History of Rome” by William Smith (1881)

William Smith was an English lexicographer who lived from 1813 to 1893. He published a more easily digestible work of Roman history than did Gibbon and Merivelle. Although his history was indeed small, Smith found a place for the diminutive and nominal last Roman Emperor in Italy:

Orestes gave the throne to his son Romulus, to whom he also gave the title of Augustus, which was afterward changed by common consent to Augustulus. But Odoacer, the leader of the German tribes, put Orestes to death, sent Augustulus into banishment, with a pension for his support, and, having abolished the title of emperor, in A.D. 476 declared himself King of Italy.

Smith notes that Augustulus was Romulus’s nickname at the time of his reign. Furthermore, like the majority of the texts, Smith has Odoacer banishing Augustulus with a pension.

Procopius With an English Translation by H.B. Dewing

Procopius was a Byzantine historian who was active in the sixth century. The text I am citing to here is an English-language translation of his work by H.B. Dewing, first translated in 1920.

Procopius did not provide an age for Augustulus, stating only that he was a child. Dewing translated Procopius’s statement on Odoacer’s deposing Romulus Augustlus:

And when [Odoacer] had received the supreme power …, he did the emperor no further harm, but allowed him to live thenceforth as a private citizen.

Procopius said nothing about Romulus Augustulus’s activities as a private citizen.

“The Great Sieges of History” by William Robson (1856)

As the title of the book suggests, The Great Sieges of History reviews history’s great sieges. While I am not sure that Odoacer’s march to Ravenna qualifies in military terms, I suppose it does in importance. I will skip to where Robson describes Romulus Augustulus’s resignation:

Augustulus, abandoned by everybody, stripped himself of his dangerous dignity, and delivered up the purple to his conqueror, who, out of compassion for his age, left him his life, with a pension of six thousand golden pence, that is, about three thousand three hundred pounds sterling.

After describing Odoacer’s march toward Ravenna as creating “frightful carnage,” Robson provided a gentle account of Odoacer toward the deposed Romulus Augustulus.

“The Age of Justinian and Theodora” by William Gordon Holmes (1912)

Holmes history of the reign of Justinian in the East includes a brief passage on the fall of Rome in the West:

Odoacar was the head of the barbarians in Italy, whilst a youth named Romulus Augustulus was formally recognized as Emperor. The potent barbarian abolished the Imperial throne and relegated its occupant to a decent exile in the castle of Lucullus in Campania. At the same time he deprecated the anger of Zeno, the Eastern Emperor, and forwarded the Imperial regalia to Constantinople in token of his submission to him as a vassal.

While Holmes was light on details, he notes that Romulus Augustulus was sent “to a decent exile in the castle of Lucullus in Campania” – which is in accord with most of the texts.

“A History of Germany” by Bayard Taylor (1882)

Bayard Taylor was a nineteenth century American translator and diplomat. Taylor’s A history of Germany was published posthumously. It is noteworthy among our texts in that it appears to draw from different sources than did Gibbon and the English historians. The pertinent section reads as follows:

Odoaker … took the boy Romulus Augustulus prisoner, banished him, and proclaimed himself King of Italy, in 476, making Ravenna his capital.

Unlike most texts, Taylor says nothing of Odoacer giving Romulus Augustulus a pension or ensuring that he had reasonable accommodations in banishment. As we will find in my conclusion section, some of the ancient accounts reported Romulus’s being banished without any mention of a pension or otherwise generous accommodations. Although Taylor’s discussion of the matter is short, it seems to be likely that he credited different accounts than did Gibbon and the majority of English histories from the nineteenth century that followed Gibbon’s lead.

“The Holy Roman Empire” by James Bryce (1871)

James Bryce was a nineteenth century professor in England. His history of The Holy Roman Empire briefly touched on Odocaer’s deposing Romulus Augustulus:

When, at Odoacer’s bidding, Romulus Augustulus, the boy whom a whim of fate had chosen to be the last Caesar of Rome, had formally announced his resignation to the senate, a deputation from that body proclaimed the Eastern court to lay the insignia of royalty at the feet of Eastern Emperor Zeno.

Bryce offered no other details about Romulus Augustulus, but this telling is notable for its statement that he announced his resignation as emperor to the Roman Senate – a fact not specified in all of the texts.

Conclusion: A Modern Take

In last year’s article, I examined differing accounts of Romulus Augustulus’s fate with reference to an article by Mr. Ralph W. Mathisen, a professor of classics at the University of Illinois.

Mathisen cited to the original source material underlying the histories that are available on Project Gutenberg. In sum, all of the histories agree that Odoacer spared Romulus Augustulus’s life. Furthermore, the accounts that discussed the fate of Romulus Augustulus with specificity generally agree that Odoacer had him sent to the Lucullan castle in Campania.

The difference in accounts appears to be one of tone. Some of the ancient writers described Augustulus as being banished or exiled to Campania, without mention of a pension or allowance. Other accounts, likely relied upon by Gibbon, described Odoacer giving Romulus Augustulus a generous pension.

Mr. Mathisen noted that one account, that of Anonymous Valesianus, reported that Romulus Augustulus ruled for a decade (for this he has no explanation). He added that it has been suggested that Theodoric, the Ostrogothic King of Italy who deposed Odoacer in 488 and ruled until 526, was writing to Romulus Augustulus in a letter he addressed to “Romulus,” sometime between 507 and 511.

Open Questions

While I stated that the purpose of this article was not to reach conclusions, it seems generally well-settled that Odoacer spared Romulus’s life and sent him to Campania. There are, however, two open questions that will likely never be resolved. First is whether Odoacer gave Romulus a pension or whether he exiled him without one. Second is how long Romulus lived post-reign. Gibbon speculated that Romulus did not live long, but Mathisen noted that some believe that Romulus and his mother played a role in the establishment of the church and monastery centered on the remains of St. Severinus.

While there is, as Mr. Mathisen noted, evidence that can be interpreted as pointing to Romulus being alive as late as 511, Mr. Mathisen is confident that Romulus was dead by the time Justinian invaded Italy in the 530s. As evidence, Mr. Mathisen noted that Procopius – who we cited to in our survey – made no mention of Augustulus being alive in his account of Justinian’s campaign.