On September 29, 2024, I reviewed a visual novel called The Dandelion Girl: Don’t You Remember Me? As the name suggests, The Dandelion Girl is based on Robert F. Young’s 1961 science fiction short story of the same name. In my review, I noted that the version of The Dandelion Girl that I was reviewing was a 2016 remake or remaster of a previous Dandelion Girl visual novel, which had been released on February 19, 2010. At the time I reviewed the 2016 Dandelion Girl, which is readily available as a freeware download on Steam and Itch.io, I stated that I hoped to also read the 2010 original version because the team behind the 2016 remaster noted that they had modified the original script. Unfortunately, I had been at the time unable to track down the 2010 Dandelion Girl.

(For those who are interested, you can read Robert F. Young’s short story here or in PDF form. That archived link comes courtesy of Wikipedia’s page about the short story.)

Not long after I published my review, a reader sent me an email with a link to a Mediafire download for the original 2010 Dandelion Girl. I was able to download the novel and confirmed that I could run it natively on Linux, albeit with a necessary tweak that I will discuss below. In this article, I will review the 2010 Dandelion Girl with a particular focus on how it differs from the 2016 version I wrote about previously.

In order to avoid re-inventing the wheel, I will structure my review of the 2010 Dandelion Girl as a companion article to my review of the 2016 re-master in a way that either presupposes familiarity with my review of the 2016 version or with either or both versions of the game. In this review, after some specific notes regarding downloading and installing the original version, I will focus on highlighting differences between the two similar adaptations of Young’s short story before offering my subjective opinion of the adaptation choices in the original 2010 version (I wrote in length about my opinion of the choices made in the 2016 version). However, neither this review nor my previous review spoil the late twists in The Dandelion Girl story, so you may consider both safe to read with or without prior familiarity with the short story or the visual novels.

The Dandelion Girl (2010) Details

I quote from the brief introduction I provided to the original Dandelion Girl project in my review of the 2016 remaster:

The Dandelion Girl was first made available in 2010 on the website of Ed Michaels, who I believe was the lead developer. There, he presented the novel as Dandy Girl. The website is no longer live but you can view an archived capture of the website here. Mr. Michaels noted he was not the sole developer, writing that most other developers who worked on the project “chose to remain anonymous.”

Thanks to one generous reader, I can now point readers to a download for the original 2010 Dandelion Girl:

The reader found this working download link in a 2010 forum thread (non-https, you can alternatively view my Internet Archive capture of the forum).

(Note: The Visual Novel Database entry for The Dandelion Girl, which covers both the 2010 and 2016 versions as well as several non-English localizations of both, has a download link for the 2010 version. However, as of the publication date of the instant article, that download link does not work.)

Like its 2016 successor, the original Dandelion Girl was written in ONScripter, a free and open source implementation of the popular Japanese visual novel scripting engine, NScripter. ONScripter is most often used for localizing NScripter visual novels into different languages – see for example the various flavors of ONScripter-EN used to localize more than 20 Japanese NScripter novels for the 2005, 2006, and 2008 al|together Festivals. One reason I was originally interested in reviewing The Dandelion Girl was because it was one of a very small number original English language visual novels (OELVNs) written in NScripter/ONScripter that are listed on Kaisernet website, which contains a useful directory of NScripter/ONScripter novels available in English.

Running The Dandelion Girl

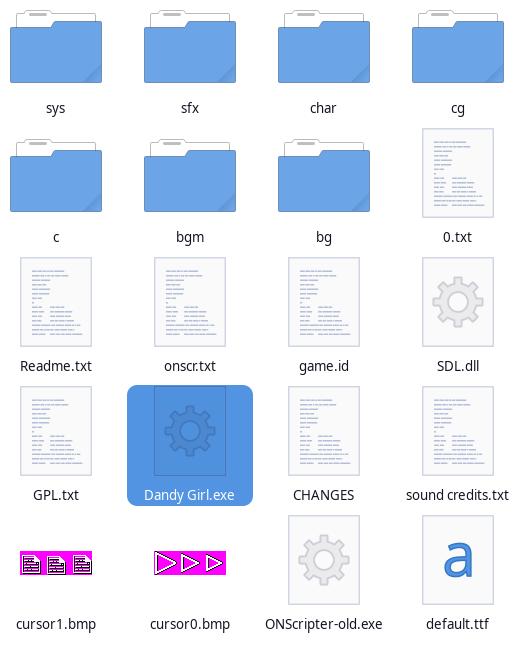

The Dandelion Girl comes packaged as a zip file. Once it is unzipped, the extracted directory, “Dandy Girlv.1.1”, contains all of the novel’s files and two executables for actually launching the novel.

Both of the provided executables, “Dandy Girl.exe” and “ONScripter-old.exe” are Windows executables.

Running Windows Build With WINE

Regular readers will know that I run Linux on all of my computers and that ONScripter games can generally be run natively on Linux, but I decided to first test the Windows build with the “Dandy Girl.exe” executable on top of the WINE compatibility layer. (Note that if you are using Steam, Lutris, PlayOnLinux, or another graphical front-end, the .exe file is not an installer, it is ready to launch so long as it is in the game’s directory.) I used Lutris as my WINE front-end and tested it using my system WINE (WINE-Staging 9.22):

The original Windows executable packaged with The Dandelion Girl launched with the help of WINE with no issue and appeared to run as expected. Moreover, the reader who found the game also ran Linux and noted that he had a good experience running the bundled Windows executable using Steam and its Proton compatibility layer (I previously wrote about setting Japanese language environments in Steam).

If you use Windows or are content running The Dandelion Girl on top of WINE or Steam-Proton, feel free to skip ahead. The next sub-section deals solely with issues inherent to running it natively on Linux.

Troubleshooting Running Dandelion Girl Natively on Linux

Having confirmed that I could run The Dandelion Girl’s bundled ONScripter executable on top of WINE, I wanted to try running The Dandelion Girl natively on Linux. While it does not come with a Linux ONScripter-EN build, I noted in my review of the 2016 The Dandelion Girl that it worked perfectly on Linux with the newest version of ONScripter-EN, which is free to download from its source code repository on GitHub. (Note: The game’s Readme, available in its directory, advises Linux and Mac users to “download the latest build of ONScripter for the relevant OS.” While this is sound advice, the link in the Readme is dead, so do not use that link.) The new versions of ONScripter-EN work without issue on the vast majority of older ONScripter-EN games I have played, including most of the al|together translations from 2005-08. I had no reason to expect that I would run into an issue.

Alas, I would have an issue – but fortunately it turned out to be a fixable issue. But first, let us go step-by-step.

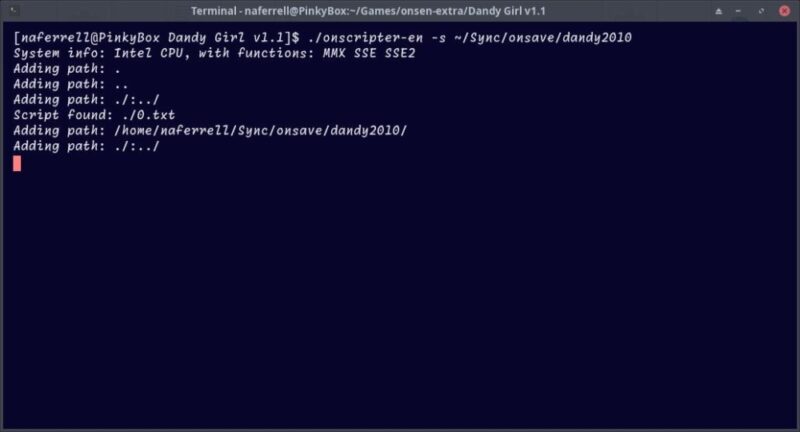

I downloaded the newest Linux build of ONScripter-EN from its GitHub repository. As of this test, the most recent build is version 2024-07-21. I then extracted the file from the archive and placed the executable, “onscripter-en”, in the novel’s directory. Linux users can launch the novel by double clicking the executable, but I launched it from the terminal so I could designate a save path.

The novel launched as expected, but I had a strange issue…

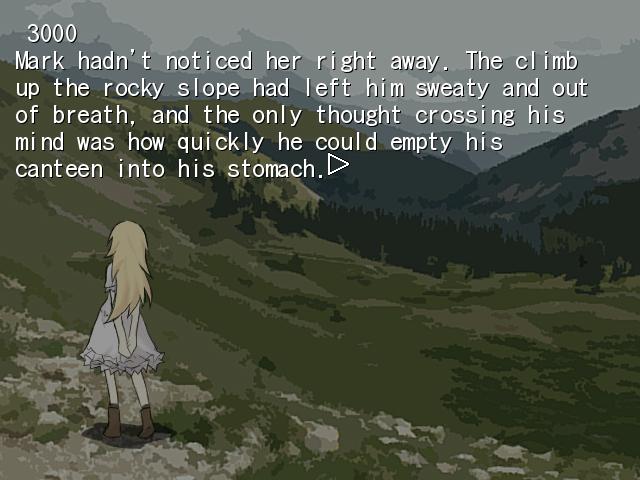

In several instances, the novel skipped through dialogue or scenes before I could see what was happening, and in others, a number, usually 500, 1000, or 3000, rendered above the text.

This did not happen when running the Windows executable on top of WINE. I correctly guessed that those numbers represented delays, as in they were different values for keeping the scene from progressing for a certain period of time. For whatever reason, they were not being handled as intended by the native Linux ONScripter-EN. I will note additionally that I also tested an older 2012 Linux build of ONScripter-EN and had the same issue – so it is not particular to the up-to-date version. Before giving up and running the Windows version, I decided to see if I could fix the issue by modifying the game’s script. ONScripter games have a text file called 0.txt which contains the script and all of the ONScripter commands.

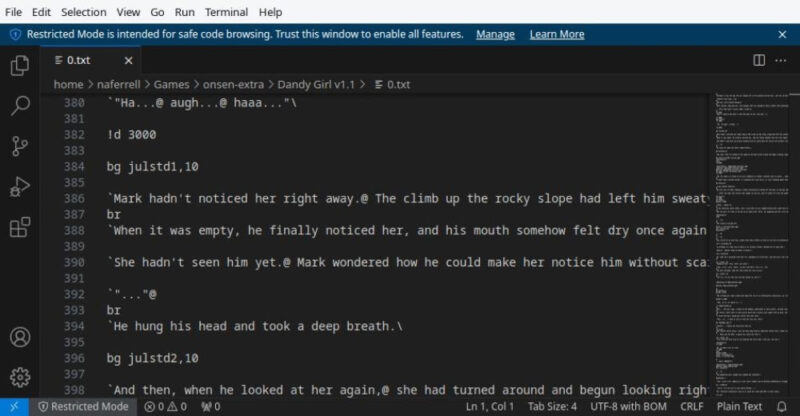

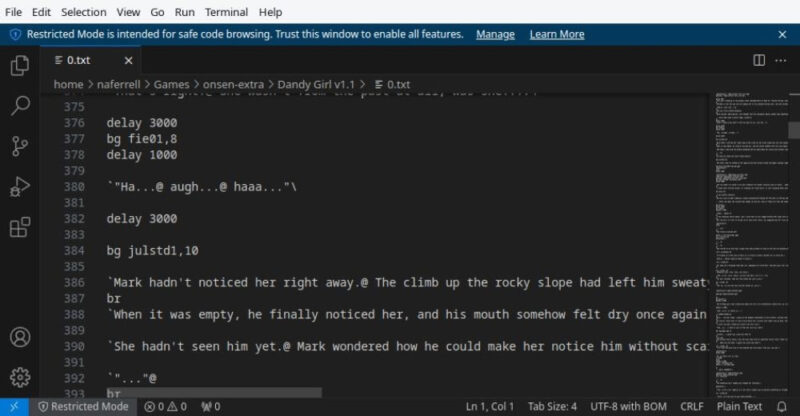

I noticed that all of the values for delay were prefaced with “!d”, see for example the script for the scene in the above screenshot.

I wondered if I could change !d to something which cooperated with the Linux ONScripter-EN. I am not actually an ONScripter expert, so I turned to the NScripter API Documentation on GitHub. According to the documentation, !d is indeed a “delay” command. However, it notes that one can use “delay” instead of “!d” – with the only technical difference being that “delay” supports variables. I decided to test replacing every instance of “!d” in the 0.txt file with “delay” using VS Codium.

Then I launched the Linux ONScripter-EN again.

As you can see, the “3000” is no longer visible. My review is based on the Linux build of The Dandelion Girl with my small modification to the script.

After I replaced !d with “delay,” everything appeared to work as expected – or so I thought. Everything was going along well until I saw the number 2000 appear a couple of times on its own line in the dialogue, notably when Julie begins talking about her dress. I checked the 0.txt file and saw that it has some instances of “!w” followed by a number denoting milliseconds. According to the API documenation, !w is a “wait” command which works similarly to delay, but the difference is while delay can be interrupted by clicks, wait cannot. Also similarly to !d, “wait” can be used instead of “!w” with the difference being that “wait” supports variables. I decided to try replacing every instance of “!w” with “wait” and sure enough my issues were again resolved.

(Note: I do not know as of the publication date of thsi article why the !w and !d are picked up running the original ONScripter-EN executable with WINE but not with the new ONScripter-EN on Linux.)

The Dandelion Girl Overview

To begin, I incorporate by reference the overview section I wrote about the 2016 Dandelion Girl. If you are not already familiar with either the 2010 or 2016 versions of the visual novel, I recommend that you read that first (note I recommend reading that section if you are only familiar with the short story). Here, I will offer some specific addenda and notes regarding the 2010 version of The Dandelion Girl vs the 2016 version.

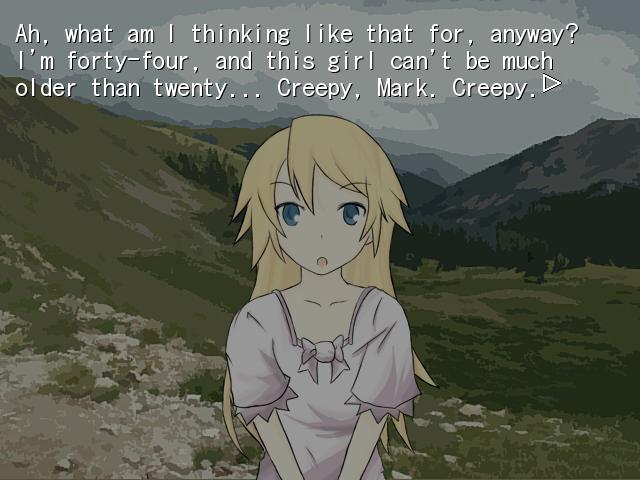

The 2010 version of The Dandelion Girl, just like the 2016 version, is told from the perspective of Mark Randolph, a middle-aged lawyer. However, Mark states in the 2010 version that he is 44, which is the same age he is in Robert F. Young’s source novel. The 2016 version leaves Mark’s precise age unstated. Mark begins the story while alone on vacation. He was supposed to be accompanied by his wife, Anne, but she was unable to join him due to jury duty – which is consistent in all three versions of the story. The 2016 adaptation had Mark note that his college-aged son had been with him on his vacation until shortly before the beginning of the story, but there is no reference to that in the 1961 novel or in the visual novel being reviewed here.

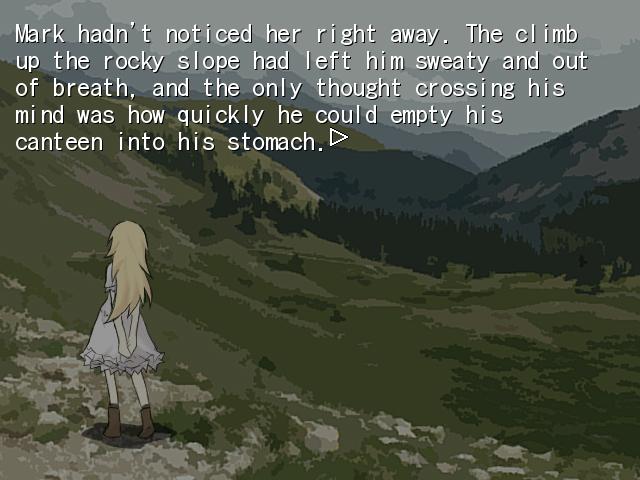

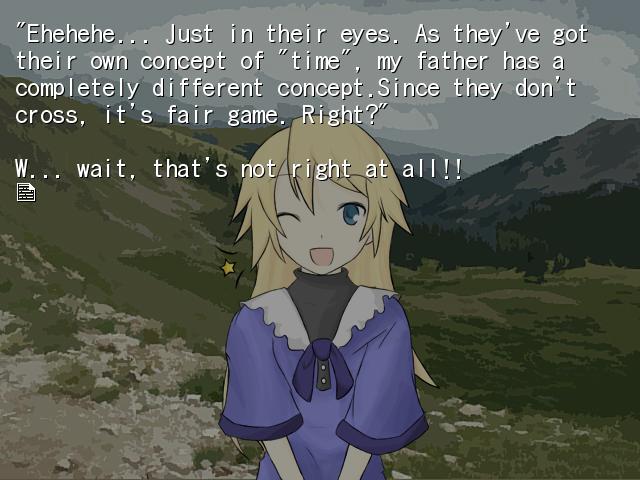

While hiking up a hilltop, Mark encounters a whimsical girl with dandelion-colored hair named Julie Danvers. Julie and Mark strike up a conversation and Julie reveals that she is from 240 years in the future – which Mark finds difficult to believe. Both versions of the visual novel make a bigger point of Mark not believing Julie than does the source novel – which is perhaps a consequence of Mark being the view-point character in the visual novels while the source novel’s story is told in the third person by the author. The 2010 version of the visual novel differs from the 2016 version in that Mark is less able to conceal his disbelief of Julie’s story and more pointed about not believing her in his internal narration – much to Julie’s playful chagrin.

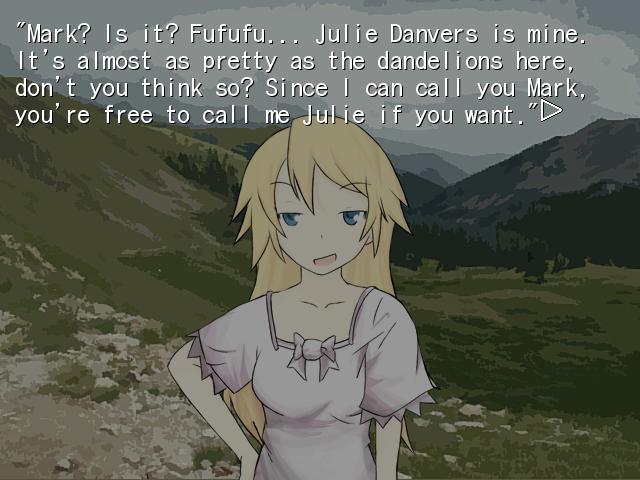

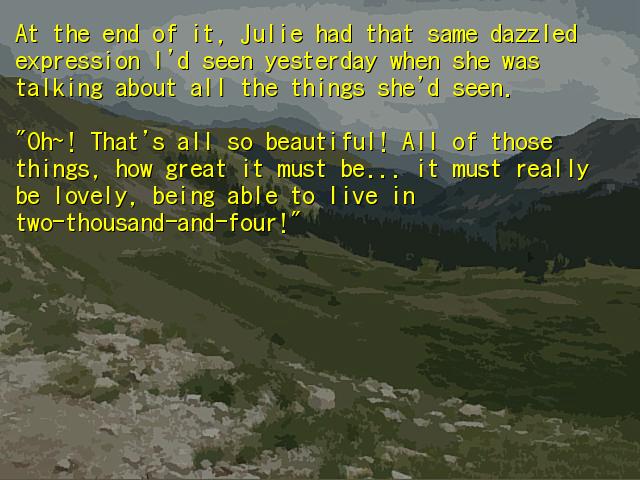

In both versions of the visual novel, Julie states that she is 17 – but in the 2010 version alone Mark initially describes her as looking to be about 20 (while opining that she could be younger before learning that she was in fact younger). Julie is 21 in Robert F. Young’s source novel. Another notable difference in the pieces is when the “present” transpires. The 1961 short story takes place in September 1961. The 2016 visual novel takes place in 1966. In my review of the 2016 visual novel, I explained how setting it in 1966 instead of 1961 like the short story resulted in some significant differences between it and the short story. I was very surprised when, close to the one-third mark of the 2010 visual novel, it is revealed that the “present” is 2004 of all times – and that Julie claims to be a time traveler from 2244.

The other points in my overview of the 2016 visual novel apply broadly to the earlier 2010 version. Of some significance, however, is that the 2010 novel is shorter – cutting out what is the third meeting between Mark and Julie that occurs in the 2016 novel and also in the 1961 source short story. The post-completion extras reveal that Julie did have a sprite for that third meeting, but I suppose it was left on the cutting room floor for the 2010 project. In any event, that third meeting only occupies a single paragraph in the original short story (it was expanded in the 2016 visual novel).

Technical Overview

To begin, I incorporate by reference my technical overview of the 2016 Dandelion Girl because the 2016 remake is substantially similar to the 2010 original that we are discussing here.

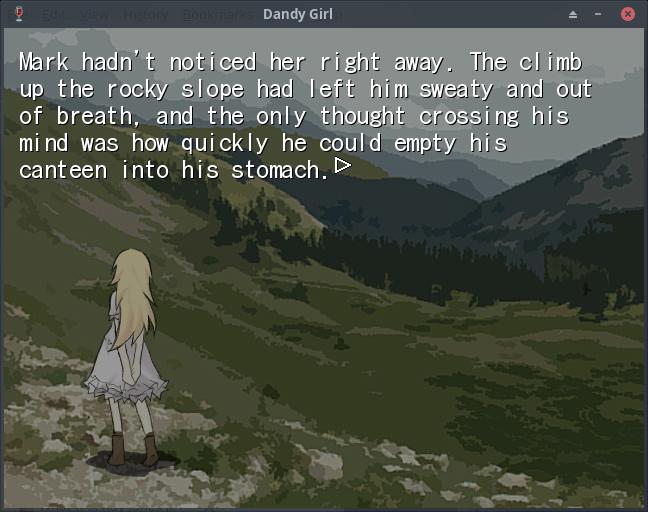

The 2010 Dandelion Girl has many of the visual hallmarks of a visual novel written in NScripter or a derivative thereof, a characteristic shared with the 2016 version. It is also an NVL-style visual novel, meaning that the text overlays the backgrounds and covers most of the screen. One minor but notable difference between the 2016 and 2010 versions is that the 2016 version has a mostly-transparent text box overlaying the background whereas the 2010 version simply overlays the text without a box. I think that the 2016 novel made a minor but welcome improvement in implementing a semi-transparent text box and it is superior aesthetically to the 2010 original largely as a result of that decision. The 2016 version of Dandelion Girl also has the better of the menus – it replaced the mostly ONScripter-default menus in the 2010 version with stylized menus which, at the very least, are an improvement.

The 2010 and 2016 versions of The Dandelion Girl share most of their character sprites (Julie Danvers is, with a few limited exceptions, the only character with a sprite) and the background images, with the background images in both versions being modified photographs. However, the overlap is not perfect – I think (albeit I did not count) that the 2010 version has more total backgrounds than the 2016 remake, despite the 2016 remake being a longer piece. However, there are backgrounds new to the 2016 version which did not appear in 2010. The CG images are the same although some unused CGs from the 2010 version made it into the 2016 version. As I noted earlier – there is one Julie sprite from what is her third meeting with Mark in the 2016 version which was designed for 2010 but went unused in that piece.

As a result of 2016 having a longer script, I would estimate that it takes about 15-20 minutes longer to read – with the 2010 edition taking somewhere in the 30-40 minute range – although I was not timing myself playing either version.

Like the 2016 version of Dandelion Girl, 2010 has post-completion extras which are unlocked on the start menu after reading through the entire novel once. The extras are mostly similar between the versions – for example, much of the unused and joke art are the same in both. As I noted, some of the unused art from 2010 made it into 2016 and some scenes from 2010 were either excluded from 2016 or effectively re-written. The two most unique extras in the 2010 version are developer commentary – one section of which I excerpted in the section about modifying the 0.txt file to make the novel run correctly on Linux, and an “unused scene” which plays off a specific scene in the 2010 Dandelion Girl which was written very differently in both the 2016 remake and Robert F. Young’s 1961 short story.

Comparing the 2010 Dandelion Girl to its 2016 Successor

One of the lead developers of the 2016 Dandelion Girl stated in pitching the release that the team had written an entirely new script while keeping most of the assets from the 2010 version. I confirmed that this is true after reading the first version of The Dandelion Girl. However, both visual novels are similar enough that I begin here by incorporating by reference two sections from my review of the 2016 The Dandelion Girl and focusing on discussing how the 2010 version differs both from 2016 and the original 1961 short story, all without undue discussion of spoiler points.

- Writing and Story Review (in and of itself)

- Differences Between the Visual Novel and Young’s Short Story

I previously praised the 2016 Dandelion Girl for its choice of making Mark Randolph, the principle main character in the short story, the view-point character and narrator of the visual novel. It turns out that this decision derived from the 2010 novel, which also makes Mark the view-point character and narrator. In contrast, the 1961 short story is narrated from the author’s perspective. For example the author, being Robert F. Young, tells readers what Mark is thinking instead of leaving it to Mark to narrate his own thoughts. Making Mark the narrator is the correct choice for a visual novel – although it necessarily does away with some of the subtlety in the story-telling of the original work.

The beginning of the 2010 Dandelion Girl, specifically Mark’s first meeting on the dandelion-covered hilltop with the whimsical Julie Danvers, hews more closely to the 1961 short story – to the point of lifting key portions of Julie’s dialogue – than does the 2016 version. However, by the end of the novel, I came away with the feeling that the 2016 version on the whole was closer to the 1961 work.

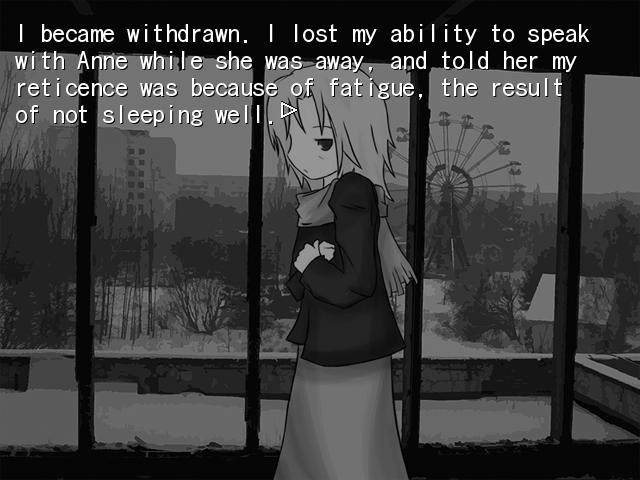

One place in which the 2010 visual novel stays closer to the source than does the 2016 version is Mark’s relationship with his mostly-unseen wife, Anne. In every version of the story, Mark finds himself on vacation alone after Anne, who had planned to go with him, found herself forced to remain behind for jury duty. The 2016 novel adds some flourishes – giving Mark a college-aged son who had accompanied him on vacation until right before the beginning of the visual novel’s story. It also tries to go beyond both the 2010 visual novel and the original short story in including details about Mark’s and Anne’s relationship. These details are absent from the 2010 visual novel as well as from the 1961 short story. On the whole, the 2016 visual novel goes through the most pains to paint Mark as suffering from general malaise even prior to meeting Julie Danvers – although generally similar sentiments are included in the 1961 work. While Mark’s encounter with Julie is what causes him to feel the most unease in every version of the piece, the 2010 visual novel focuses more more on that as the sole cause of Mark’s angst than does the 2016 version.

I noted my negative opinion of changing Julie Danvers’ age from 21 (in the short story) to 17 (in the 2016 visual novel). Julie is also 17 in the 2010 visual novel, although Mark initially guesses that she is about 20. The 2010 visual novel specifies that Mark is 44. His age is left unstated in the 2016 remake but he is 44 in the 1961 short story. My negative opinion of making Julie 17 instead of 21 is the same with respect to the 2010 novel as it was with the 2016 novel – albeit the consequences of her age play out a bit differently. One positive point in the 2010 visual novel’s favor is that – on the whole – Julie comes off as slightly more mature, especially in the early-going. The 2010 novel fortunately lacks some of Julie’s Key visual novel-style verbal tics included in the 2016 version, in which she comes off as younger, especially when coupled with the strange Japanese-inspired choice to have Mark repeatedly scold Julie for calling him “Mr. Mark” – something I call strange because it does not make sense in English. In the 2010 novel, Julie and Mark initially agree to call each other by their first names, although Julie oddly lapses into “Mr. Mark” in the second half of the piece (it is not commented upon). However, with the exception of Julie’s laughter in the 2010 piece, her Key-esque verbal tics are mostly an innovation of the 2016 version of the visual novel. But setting aside the differences between the 2010 and 2016 visual novels, Julie comes off as younger and more immature in both pieces than she does in the original short story. The Julie of the short story is whimsical to be sure, but measured and intelligent – she is able to converse with Mark about philosophers and scientists and, while the short story only relates excerpts of their conversations, it seems plausible that Julie is charismatic and intelligent enough to captivate Mark. While the visual novels do not change the underlying scenario between Mark and Julie, they rely more on Mark’s loneliness and unexplained feeling of deja vu to explain his quickly taking to Julie. Both of those are key points in the short story as well – but Julie herself is a stronger character in the original work, even without the benefit of her well-drawn depiction in the visual novels.

The 2010 visual novel handles Mark’s feelings for Julie more directly than does the original short story or 2016 remake. Mark’s internal monologue in the 2010 visual novel when he is apart with Julie comes off as tormented by his attraction to her – both because of the age difference and because he is happily married, or somewhat happily, at least. To be sure, Mark’s discomfort about his odd feelings for Julie are present in the 2016 novel as well as the 1961 short story, and all three pieces make a point of noting how it creates some unease in his marriage, but the 2010 novel hammers home Mark’s attraction more than either of the other works. On this point, the 2010 novel draws the worst hand of the three Dandelion Girls in two respects. One thing that makes the 1961 short story a compelling read is that Mark’s conflicts, his unease, and their ultimate resolution were handled subtly. It is clear that Mark has complicated feelings for Julie and that these feelings make him uncomfortable on multiple dimensions without repeatedly saying as much – the author tells, but takes more of a show approach. The 2016 novel also makes less of a point of repeatedly articulating home Mark’s attraction to Julie and more to considering the multiple reasons he feels odd about her and how it affects his feelings about his marriage. Having noted that Julie is generally slightly more mature in the 2010 novel than in the 2016 counterpart (to the benefit of 2010), Mark’ character is slightly less measured and mature in 2010 than in 2016, which goes the other way and favors the re-make.

The 2010 visual novel handles Mark’s last meeting with Julie on the hilltop significantly differently than the 1961 short story or 2016 visual novel remake. This is one of the two most important scenes of the story and to go into detail would be to veer into spoilers, but Julie’s emotions are rawer and more visceral in the 2010 work than the 2016 short story, much less Julie’s comparatively more measured portrayal in the short story. While I do not begrudge the 2010 team’s interpretation of Julie’s feelings in this scene, I think it goes a bit overboard – especially given what we already know about Julie. Moreover, it portrays Mark in a way that complicates, or at least muddles, the ultimate conclusion of the story.

This segues into my biggest issue with the 2010 visual novel vs the 2016 remake and why, despite some of my issues with the 2016 take, I think the remake ultimately has the better of the script debate. I will have to pull my punches on this issue to avoid spoilers since it relates to the ultimate conclusion of The Dandelion Girl. Julie relates a theory to Mark in their second meeting – and that theory is related the same way in the visual novels as in the short story. Only in the 2010 version of the visual novel does Mark do his own internal wrestling with the Julie’s theory – and I dare venture that I suspect the way Mark goes about considering the theory played a role in the team’s decision to set the novel in 2004. Then we skip ahead to Mark’s and Julie’s final meeting – here Mark is again wrestling with the same theory in the 2010 version and the scene is simultaneously dominated by Mark’s and Julie’s more visceral emotions. These two points influence the conclusion of the 2010 visual novel. To be sure, The Dandelion Girl concludes the same way – in terms of what ultimately happens – in all three cases. But the 2016 adaptation does a better job of capturing what I think was the central point of the original short story – to avoid spoilers I will summarize it as sometimes someone is exactly where he or she is supposed to be. Again noting I had some issues with certain adaptation choices in the 2016 version, the central message comes through. In the 2010 version, the central message is muddled by Mark’s theorizing and what I consider the novel’s unfortunate choice to tell instead of show in the finale. Regarding the finale, I was not entirely on board with the 2010 novel’s interpretation of why a certain character left something unsaid, but I do not begrudge it for offering its own take outside of my critique of telling instead of showing.

Finally – I reach what may be the most curious decision of the 2010 adaptation. I did a double take when it was first noted that the events of the novel take place in 2004. As I noted, the short story takes place in 1961 and the 2016 novel in 1966. I noted with respect to the 2016 novel I had some suspicions as to why the team set its story in 1966 instead of 1961 and I appreciated what they tried to do – placing a greater emphasis on Mark’s past military service – even though I did not think it fully pulled it off. But why is the 2010 version set in 2004? It is not clear to me and I suspect the answer may be, in light of Mr. Michaels’ noting in the post-completion extras that the project took a long time to complete, that the loosely assembled team began working on The Dandelion Girl in 2004 (that is just my speculation, however). One would think if one makes the decision to set a story in 2004 instead of 1961, there would be an obvious reason for doing so and some material changes to the story. But it is hard to highlight many points where it makes a difference. I will submit that in the 2010 version some of Mark’s dialogue and internal monologue feels more 2004 than 1960s; , see for example my note on his wrestling with Julie’s theory. Mark had still served in a “war” in the 2010 version – although it is less than clear which war he would have served in (it is almost certainly World War II in the other two Dandelion Girls). One scene where Mark smoked a pipe in the original work becomes a cigarette in the 2010 version without changing enough dialogue to cover the alteration. Finally, there is one stray reference in the 2010 version to computers that would have been out of place in the original timeline. In the end, placing the events of The Dandelion Girl in 2004 instead of 1961 in the case of this adaptation had surprisingly little impact. I would have been interested in seeing the team try to do a little bit more with the idea.

Conclusion

I had been curious to compare the 2010 version of The Dandelion Girl to the 2016 remake I played first to evaluate the changes made in the second version. Taken together, I think that the 2016 remake is the better Dandelion Girl visual novel. The 2010 version handled Mark’s and Julie’s first meeting better than did the 2016 version, and it would have been a stronger piece had Julie been written more like she was for that first meeting for the entire story. The 2010 version’s omission of some of the 2016 version’s additional story-points is not, on the whole, necessarily a flaw. But beyond the first day – the 2016 version’s story generally has the better of things, adding its own flourishes to the story but doing a better job of delivering the message at the core of Robert F. Young’s work in the final analysis. Its excesses in making Julie at times a bit too weird and some interesting additions that were not ultimately fully justified are not enough to tip things in the 2010 version’s favor. We can add the improved presentation and welcome extra length in developing Mark’s and Julie’s relationship to the list of factors favoring the remake version. But while I prefer the remake, it owes a great debt to the 2010 version – to that end most of the screenshots would be indistinguishable without the stylized text box in the remake.

Having considered two adaptations of The Dandelion Girl, I submit that the character of Julie provides the most room for a re-interpretation. However, instead of reducing her age by four years and giving her the verbal tics of a weird bishoujo heroine, I would recommend approaching her claiming to be from the future from a different character. Robert F. Young wrote the original short story in 1961 and imagined Julie from that perspective. Someone adapting the work decades later could plausibly imagine the future Julie comes from, and how it may shape her character, differently than did Young in the original work. While the two visual novels certainly reimagined Julie to a point, I do not think they did so in what could have been the most interesting way.

If you are looking for my recommendation – I would suggest reading Robert F. Young’s short story first since it is the best version of The Dandelion Girl and the best way to experience it in the first instance. My overall view of the visual novels is generally positive when considering the medium, and I would recommend beginning with the ultimately superior 2016 piece. If you are a fan of the story or simply interested in seeing some dramatically different choices in adapting it to different media, I would also recommend reading the 2010 version and coming to your own conclusion about the choices it and the 2016 remake made in adapting a classic science fiction short story into the visual novel format.