For our first Around the Web of May, I will examine four May issues of The Nursery: A Monthly Magazine For Youngest Readers. Project Gutenberg currently has 48 issues of the nineteenth century children’s serial in its library. Because we are now entering May, I will examine the four issues in Project Gutenberg’s collection that were published in May – 1873, 1875, 1877, and 1881. For this post, we will look at a couple of articles and poems from each of the four May issues of The Nursery Magazine.

Good-morning, sir! Come in! Don’t make yourself a stranger. Hard times these, but you will find plenty of crumbs on the table. Don’t be bashful. You don’t rob us. Try as you may, you can’t eat us out of house and home. You have a great appetite, have you? Oh, well, eat away! No cat is prowling round.

From “Good-morning, Sir!” (see 1877 issue)

Before beginning, I will note that I was unable to find much information about The Nursery other than that it was published in Boston – so I will allow the content of the magazines to speak for itself. All of the pictures that I will use in the article are the original pictures from the magazine for the articles and poems that I summarize.

The Nursery Volume XIII – No. 5 (May 1873)

The May 1873 issue of The Nursery contains 13 stories, four poems, and one song – all of which you can read on Project Gutenberg. For this section, I will look at two of the short stories and one of the poems, and the song.

Naming the Kitten

Naming the Kitten is the story of two sisters, a mother cat, and a kitten. Alice, the younger sister, brought a kitten home, which already housed a mother cat.

She begged her older sister, Rachel, for permission to keep the kitten. The mother cat protested, but Rachel was unperturbed, quieting the cat with a saucer of milk. Rachel then considered the matter and told Alice that she could keep the kitten under one condition.

The condition is, that you give the kitten a name,–a name that I shall approve of.

Young Alice was eager to have a pet kitten, so she immediately began offering suggestions.

Alice confidently started with the name Arabella. Rachel did not approve:

Nonsense! that is too long and grand a name for a kitten. It will do very well for a proud lady-doll from Paris, but not for this little scratcher.

No good. Alice went for a simpler name. “How would you like the name of Betsy?” “Not at all,” Rachel replied, “I think it a homely sort of name.”

Alice could sense her opportunity to have a pet slipping away. She began throwing names at the wall:

Well, will any of these do?–Pet, Muff, Tabby, Tit, Tip-top, Scamper, Nap, Mop, Pop, Grab?

None of the names stuck. Rachel dismissed all of these desperate suggestions by suggesting that Alice had pulled them from a storybook.

Alice conceded that Rachel was correct – she had taken all of those ideas from a storybook. Alice, now frustrated, gave up on the naming the kitten – although she did not give up on keeping the kitten:

Name the kitten yourself, if none of those names will satisfy you. Put her on my lap, and I will get some cream, and let her lap it.

Finally, Rachel approved of something that her younger sister had said:

Lappit, did you say? That’s a new name, and a good one! You have hit upon a name at last. We will call the kitten Lappit.

Alice laughed, and Rachel, Alice, Lappit, and the mother cat went into the garden together.

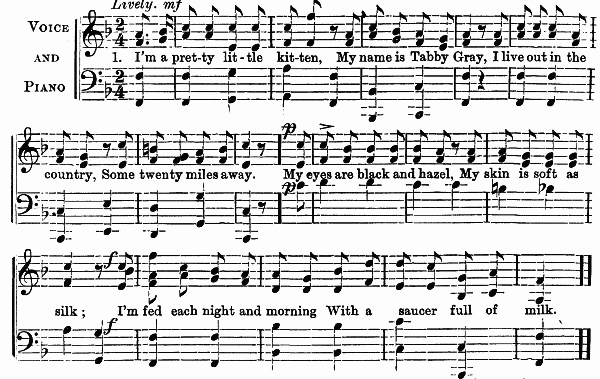

The Kitten

The May 1873 issue concluded with a song called The Kitten. Although it has no direct relationship with the story of Rachel and Alice, it seems fitting that we should follow that short story with The Kitten song. I think Victor should consider this for his next Quarantine Session.

“The Kitten”

I'm a pretty little kitten,

My name is Tabby Gray,

I live out in the country,

Some twenty miles away.

My eyes are black and hazel,

My skin is soft as silk;

I'm fed each night and morning

With a saucer full of milk

The milk comes fresh and foaming,

Fresh from the good old cow;

And, after I have lapped it,

I frolic—you know how.

I'm petted by the children,

And the mistress of the house;

And sometimes, when I'm nimble,

I catch a little mouse.

But sometimes, when I'm naughty,

I climb upon the stand,

And eat the cake and chicken,

Or any thing at hand;

Ah! then they hide my saucer,

No matter if I mew;

And that's the way I'm punished

For naughty things I do.

The Life of a Sparrow

Story Link. By “The German.”

Not since I completed my series of articles on the January 1897 issue of Birds: Illustrated By Color Photography, have we published any content purportedly written from the perspective of a bird. Today, we end the drought with an old sparrow reflecting on a life lived well. I should note that we are fond of sparrows here at The New Leaf Journal.

The sparrow begins the story by telling us that he is “very old.” He is transcribing the events of his life “for the instruction” of his children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren.

The old sparrow recounted his parents’ story of seeking a new home to accommodate the needs of their growing family. Their search proved to be fruitful:

One lovely day in spring, they came to a pretty village which pleased them, and alighted on a cherry-tree to consult together. ‘Here we will remain,’ said my father. ‘Look at the cherry-trees and grape-vines. We have found the right place at last.’

The sparrow family settled on “a new house with a projecting roof, before which stood three large cherry-trees in full bloom.”

The old sparrow’s mother laid four eggs. Only his egg hatched. He was raised well – spoiled with “tender words.” Thanks to the nutritious means, the old sparrow was soon ready to fly.

One fine day I stood on the edge of the nest, fluttered my wings, and flew out of my father’s house. With many fears and a beating heart I at last alighted on an acacia tree.

Danger in Sparrow Life

With freedom can come trouble. One day, the old sparrow flew through an open window to enjoy some grain on the floor. A little boy trapped the sparrow, clipped his wings, and took him in. Although the old sparrow noted that the boy treated him well, he yearned to be free again. Fortunately, the old sparrow’s wings grew back, and in time he was able to fly out of the home just as he had flown in, and he returned to his mother.

Danger lurks in unexpected places for sparrows. On one autumn day, the old sparrow and his mother were eating grain on a gate. They did not realize that a kitty was lying in wait. The kitty sprung into action, seizing the old sparrow’s mother. The old sparrow’s mother was “very wise,” however. She played dead, lulling the kitty into a false sense of security. The kitty carried the old sparrow’s mother to the grass where he put her down. At that moment, she flew away, too fast for the kitty to catch her again.

Starting a Sparrow Family

The old sparrow grew into an adult sparrow. He chose for himself a sparrow-wife, and defeated his many rivals for her wing in marriage. He reminisced: “My bravery won her heart; and I think she has been well content with her choice.” The old sparrow and his wife built a nest and had five children, three sons and two daughters.

One of the sparrow’s sons became a pet. The old sparrow recalled that his son had been captured by “a friendly little maiden.” She treated him well, too well perhaps – making him quite fat. The old sparrow’s love of freedom was not inherited. His son perished fat and happy, and his maiden was quite sad.

The rest of the old sparrow’s children lived to start their own families. He concluded his recollections for them:

Our other children, one after the other, founded homes of their own, and all lived good and useful sparrow-lives. The multitude of my grandchildren I am no longer able to count.

Mistress Mouse

I conclude with the final piece in the magazine that featured a cat appearance. Below, reprinted in its entirety, is the poem Mistress Mouse.

“Mistress Mouse”

Mistress Mouse

Built a house

In mama's best bonnet.

All the cats

Were catching rats,

And didn't light upon it

At last they found it,

And around it

Sat watching for the sinner;

When, strange to say,

She got away,

And so they lost their dinner.

The Nursery Volume XVII – No. 101 (May 1875)

The May 1875 issue featured 13 stories (one with several poems), four poems, and one song. Although the format was largely like the 1873 issue, the layout and structure had evolved a bit in the two years. I will cover three pieces from this issue – focusing on grandmothers and spring. You can see the entire magazine on Project Gutenberg.

Celebrating Grandmother’s Birthday

Story Link. By Emily Carter.

Four siblings – Emma, Ruth, Linda, and John – were considering what to do for their beloved grandmother’s 70th birthday. Emma, the eldest sibling, asked her three younger siblings for suggestions.

John, the only boy, had a wonderful suggestion for his sisters to consider:

Get some crackers and torpedoes, and fire them off.

John

Linda objected to that well-reasoned idea. She suggested that they serenade their grandmother instead.

Ruth, however, saw a flaw with Linda’s idea. For one, Ruth noted that none of the siblings could sing. For two, their grandmother was a “very good musician,” so she would be unlikely to enjoy poor singing. But Linda had given Ruth an idea:

Let us do this: Let us come to her as the ‘Four Seasons,’ and each one salute her with a verse.

Ruth

The siblings all found Ruth’s idea to be agreeable.

Choosing the Roles

Linda was the first to agree with Ruth’s idea, which was an addendum to her original idea. Linda seized the moment, laying claim to spring:

I’ll be Spring; for they say my eyes are as blue as violets.

Linda

Emma, the oldest sibling, claimed summer, for summer is her favorite season.

Johnny, apparently fully recovered from his fire cracker and torpedo suggestion being shot down, claimed autumn:

I’ll be Autumn, for if there’s any thing I like, it is grapes. Peaches, too, are not bad; and what fun it is to go a-nutting!

John

Poor Ruth, who had come up with the idea, was left with winter by default. “No matter! Winter has its joys as well as the rest.” I agree with Ruth – as I wrote in an article last September.

With the roles settled, there was one outstanding issue. Emma asked who would write the verses for them. Ruth replied that their teacher would do it, for “no one could do it better.” Ruth came through in the clutch again.

Setting the Scene for the Birthday

The four siblings greeted their grandmother on the morning of the 70th birthday. Their grandmother was sitting in her armchair with her cat at her side. The siblings entered the room one after another, with Linda as spring leading the procession, followed by Emma as summer, Johnny as autumn, and Ruth as winter. They formed a semi-circle around their grandmother. She smiled and waited to see what they had planned.

Below, in order, I reprint the seasonal readings.

Spring (Linda)

I am the spring: with sunshine see me coming; Birds begin to twitter; hark! the bees are humming: Green to field and hillside, blossoms to the tree, Joy to every human heart are what I bring with me.

Summer (Emma)

See my wealth of flowers! I'm the golden Summer: Is there for the young or old a more welcome comer? Come and scent the new-mown grass; by the hillside stray; And confess that only June brings the perfect day.

Autumn (John)

Mark the wreath about my head,—wreath of richest flowers; I am Autumn, and I bring mildest, happiest hours; In my hand a goblet see, which the grape-juice holds; Corn and grain and precious fruits, Autumn's arm enfolds.

Winter (Ruth)

Round my head the holly-leaf; in my hand the pine: I am Winter cold and stern; these last flowers are mine. But while I am left to rule, all's not dark and sad; Christmas comes with winter-time to make the children gald.

All the Seasons (Linda, Emma, John, and Ruth)

Here our offerings glad we bring, And long life to Grandma sing.

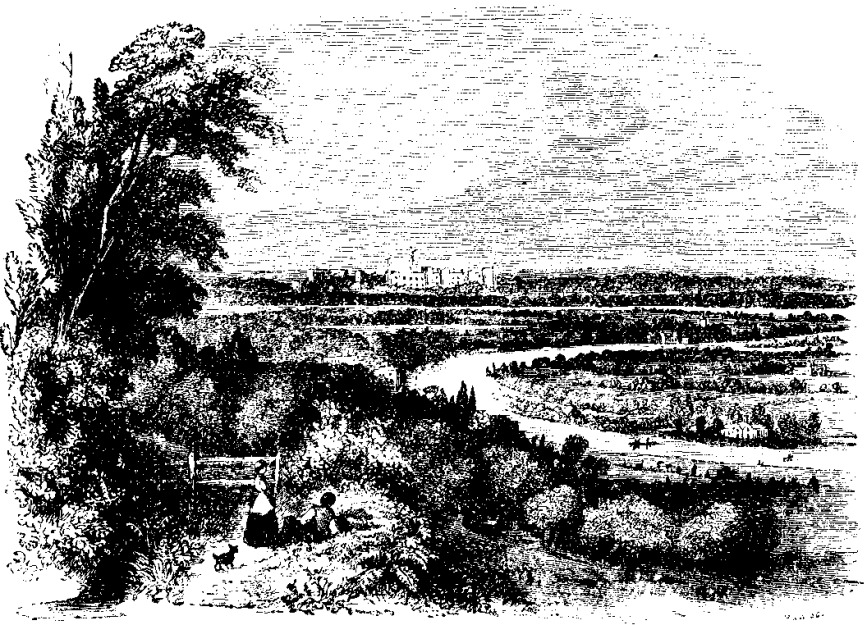

View From Cooper’s Hill

Story Link. By E.W.

The narrator of the story writes about his or her grandmother, who grew up in Windsor. Because the story is relatively short, I will reprint the original in its entirety, as it appeared in the magazine.

“The View From Cooper’s Hill”

When grandma was a little girl, she lived in England, where she was born. She lived in the town of Windsor, twenty-three miles south-west of London, the greatest city in the world.

Grandma showed us, the other day, this picture of a view from Cooper’s Hill, near Windsor, and said, “Many a time and oft, dear children, have I stood there by the old fence, and looked down on the beautiful prospect,—the winding Thames, the gardens, the fields, and Windsor Castle in the distance.

“This noble structure was originally built by William the Conqueror, as far back as the eleventh century. It has been embellished by most of the succeeding kings and queens. It is the principal residence of Queen Victoria in our day. The great park, not far distant, has a circuit of eighteen miles; and west from the park is Windsor Forest, having a circuit of fifty-six miles.

“It is many a year since I saw these places. I cannot expect to visit them again; but this picture brings them vividly before me.

“And so, dear children, should you ever go to England, don’t forget to go to Cooper’s Hill, and, for grandma’s sake, to look round upon the charming prospect which she loved so much when a child.”

May

One of the poems in the 1875 issue is called May. It is, unsurprisingly, about the month of May. Since the calendar turns to May here in 2021, I thought that this poem would make for a fitting addition to the instant article.

“May”

Pretty little violets, waking from your sleep, Fragrant little blossoms, just about to peep, Would you know the reason all the world is gay? Listen to the bobolinks, telling you 'tis May! Little ferns and grasses, all so green and bright, Purple clover nodding, daisies fresh and white, Would you know the reason all the world is gay? Listen to the bobolinks, telling you 'tis May! Darling little warblers, coming in the spring, Would you know the reason that you love to sing? Hear the merry children, shouting as they play, "Listen to the bobolinks, telling us 'tis May!"

Reading on the Bobolink

The bobolink is a small migratory blackbird that breeds in the northern United States and Southern Canada in the spring and summer. You can learn more about it on Cornell’s eBird site.

The Nursery Volume XXI – No. 5 (May 1877)

The May 1877 issue of The Nursery featured 15 stories, five poems, and one song. A couple of the stories in this issue involve horses, so I will cover both of the horse stories and two stories of avian kindness. The entire issue is available on Project Gutenberg.

The Young Lamplighter

Story Link. By Uncle Sam.

We are told that The Young Lamplighter is a true story.

Wallace, 10, and his brother Charles, 18, were the town lamplighters in a town near Boston.

As town lamplighters, Wallace and Charles were responsible for lighting the town’s 50 street-lamps. They would light the street-lamps every night. The task was made challenging by the fact that some of the street-lamps were “a good deal farther apart than the street-lamps in large cities.” Charles, being the elder brother, handled the most distant lamps.

Wallace had the service of his father’s saddle-horse. The horse was about the same age as Wallace, and was kind, gentle, and wise. Wallace and the horse had become good friends.

Every evening, ten-year-old Wallace would put the saddle on his father’s horse. The horse, familiar with the routine, knew the work ahead. The story described the horse looking into Wallace’s eyes as if to say:

We have our evening work to do, haven’t we, Wallace. Well I’m ready: jump on.

Wallace would mount the horse every evening. The horse would take Wallace to the nearest lamp-post. Upon reaching the lamp-post, the horse stood still. Wallace would then stand on his steed, take a match from his pocket, light the street-lamp, and then return to the saddle. The horse would then take Wallace to the next lamp-post, and so on and so forth.

After lighting all of the lamps, Wallace and his horse trotted home merrily. Before Wallace went to bed after their hard work, he saw to it that his trusted horse was well-fed and well-cared for.

Fanny and Louise

Story Link. By L.S.H.

This is the story of Fanny, a pony, and Louise, a little girl to whom Fanny belonged. While ponies are small, little girls are smaller.

Their Appearance

Fanny was described as having “a long black mane and tail.” She was attired in “a saddle and bridle with blue girths and reins.” For her part, Louise “had long brown curls” and “wore a gypsy-hat with blue ribbons.”

A Willful Pony, a Gentle Passenger

Louise was “a gentle girl.” She would have done well with a gentle pony. Alas for Louise, “Fanny was a very headstrong pony.” In a battle of wills, Fanny’s willfulness prevailed. For example:

When she was trotting along the road, with Louise on her back, if she chanced to spy a nice prickly thistle away up on a bank, up she would scramble, as fast as she could go, the sand and gravel rolling down under her hoofs; and, no matter how hard Louise pulled on the reins, there she would stay until she had eaten the thistle down to the very roots.

Thistles were not the only thing that caused Fanny to disregard the directions of gentle Louise on her back:

She would spy an apple on a tree, no matter how thick the leaves were;and, without waiting to ask Louise’s permission, she would run under the tree, stretch her head up among the branches, and even raise herself up on her hind-legs, like a dog, to reach the apple.

When Fanny wanted an apple, all poor gentle Louise could do was hang on for dear life:

Louise would clasp Fanny around the neck, and bury her face in her mane: but she often got scratched up by the little twigs; and many a long hair has she left waving from the apple boughs after such an adventure.

Fanny was also tempted by human culinary works. For example, there was one kitchen from which the smell of frying crullers wafted to Fanny’s nose. Fanny, quite intrigued, put her head in the window kitchen window, and waited to try one. Louise was little more than a bystander. Fortunately, the farmer’s wife gave Fanny a cruller. Satisfied with this snack, Fanny “went quickly back to the road, and behaved very properly all the rest of the way.”

Franny Meets Willful People

While Franny may not have always put the little girl on her back first, she was regarded as “a good pony.” The neighbors were quite impressed with Franny’s tricks. For that reason, they borrowed her for one reason or another (I do not suppose Louise had it in her to put up much of a fight). Franny did not like it when other people made her do things that she did not want to do, not considering her point of view.

On one occasion in the summer, the town minister borrowed Franny to visit a sick man about two miles away. The minister was very tired and warm in the summer heat. Half-way to the sick man’s house, Franny turned up lame. The minister noticed and led the poor horse instead of riding her. After the minister led Franny home, her whole family gathered around to see where she was hurt. Franny then perked up and pranced to her stable.

It had been all a trick to punish the minister for borrowing her. And it succeeded; for he never asked for Franny again.

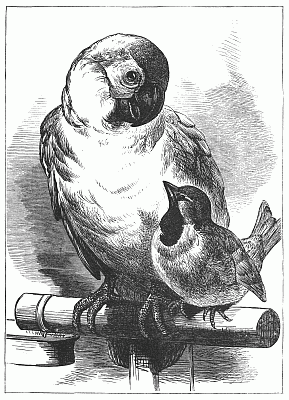

The Parrot and the Sparrow

Story Link. By Uncle Charles.

While Franny only pretended to be lame, this is the story of the time that Jacquot the parrot actually fell ill.

Jacquot lived at the Jardin des Plantes in Paris. There, he befriended a sparrow, with whom he would spend entire days sitting on the perch to which he was chained.

Their friendship was described as follows:

Jacquot … holding the sparrow at the end of his claw, would turn his head on one side, and gaze fondly on the little bird, which would flap its wings in answer to this sign of friendship. Then Jacquot would slide down to his food-tin, as if to invite the sparrow to share his breakfast.

On one occasion, Jacquot fell ill. “He trembled with fever, and looked very sad.” His sparrow friend tried and failed to cheer him up. Then the sparrow had an idea. The sparrow flew to the garden and returned to Jacquot with blades of grass. Jacquot struggled to eat the grass. The sparrow returned with more grass, and so on and so forth. After several days, Jacquot made a full recovery.

Jacquot would return the favor. One day, his sparrow friend was hopping in the grass as usual. Suddenly, a cat sprang from the bushes. Jacquot “raised a loud cry, and broke his chain to fly to the aid of his friend.” The cat fled, and the sparrow was saved.

Good-Morning, Sir!

Story Link. By Ida Fay.

In this story, the author tells the story of her sister, Helen, and her robin-friend.

A certain robin became very friendly with Helen. It would fly to Helen’s door every morning looking for crumbs for breakfast. Sometimes it would go so far as to perch on the table.

The author remarked:

It is very pleasant to form these friendships with birds; so that they learn to trust you and love you.

To the robin, Helen would say:

Good-morning, sir! Come in! Don’t make yourself a stranger. Hard times these, but you will find plenty of crumbs on the table. Don’t be bashful. You don’t rob us. Try as you may, you can’t eat us out of house and home. You have a great appetite, have you? Oh, well, eat away! No cat is prowling round.

Once the weather grew warmer, the robin visited Helen less frequently. However, “every now and then, he would make his appearance, as if it to say, ’Don’t forget me, Helen. I may want some more crumbs when the cold weather comes.”

The Nursery Volume XXIX – No. 5 (May 1881)

The final issue of The Nursery that we will cover features ten stories, nine poems, and one song. I will discuss two of the stories and two of the poems. You can read the entire issue, including the parts that I cover, at Project Gutenberg.

Papa Robin

Story Link. By Frances C. Sparhawk.

A young girl named Elizabeth was reading on her doorstep on one summer morning. She was often distracted by bustling birds and fluttering butterflies.

Elizabeth’s attention was arrested by a “shrill chirping.” She thought to herself that the chirping sounded pained, so she went into the backyard to find the bird.

Elizabeth found a baby-bird under a tree. It continued chirping shrilly. She picked it up and held it in her hand.

Elizabeth thought that it was best to return the baby-bird whence it came. She found its nest in the tree, but being a little girl, she was not tall enough to reach it. Elizabeth was clever, however, and she managed to reach the nest by standing on a knot on the tree. Elizabeth noted that the bird’s parents were in the tree. Satisfied that the situation had been resolved, she returned to her reading.

It was not long until Elizabeth was disturbed anew by the chirping of the baby-bird. Just as she had done the first time, she put the baby bird back in the nest. Little Elizabeth wondered what this bird’s parents were doing.

Elizabeth returned to her doorstep, but instead of reading, she watched the nest to see what would happen. She assumed that the parents would find a safer place for the baby-bird. Instead, Elizabeth watched the baby-bird fall from its nest again.

You stupid old Robin! Do you expect someone to be putting back your birdie for you all day? Why don’t you keep it in the nest.

Elizabeth retrieved the baby-bird for a third time. However, this time the papa Robin flew from its nest and pecked Elizabeth on the forehead.

The story concludes as follows:

Elizabeth stood still. She didn’t know what to make of this. But soon she began to laugh; and then she put the baby-bird gently on the ground, and went away. She at last understood what papa Robin meant to say to her by his peck. This is it: ‘Don’t interfere when I’m teaching my child to fly. You are very big, and perhaps you know a great deal; but you don’t seem to know that it’s not right to keep birds in the nest all summer. They would never find out what their wings are for.’

Carlo and the Ducks

Story Link. By Jane Oliver.

A young girl named Jane was walking her dog, Carlo. From the sound of the story, however, it seems that when Carlo saw two ducklings, he began walking Jane.

Jane tried in vain to restrain Carlo, who was giving chase to the ducklings. The ducklings made it to the water, and Carlo temporarily stopped. The narrator notes that although Carlo was not fond of water, he would not have stopped his pursuit on account of that. Why did he stop?

The mother duck of the ducklings emerged from the water and confronted Carlo. Mother duck stood bravely before little Carlo, and Carlo was afraid. He barked at the duck, but that only betrayed his fear.

Madam Duck did not mind his noise in the least. She quacked at him fiercely. This is what she meant to say: ‘Look here, my young friend, you are a dog, and I am a duck. You are at home on the land, but I am at home on the water. Bark as much as you please, but, if you know what is good for your health, keep out of this pond, and let my ducklings alone’

Jane seemed to understand the duck, and her sentiments were entirely in accord with her.

Did you hear that, Carlo? Now don’t stop to answer, but come with me like a good dog, and we will have a run in the woods.

Carlo, chastened, did as Jane said and continued obediently on his walk.

The May-Queen

Poem Link. By Mary D. Brine.

The May Queen is a poem by Mary D. Brine, who has many nineteenth century children’s books and stories to her name. The poem begins with a grandmother telling her grandchildren about how, as a child, she and her friends would crown a May-day queen. The grandchildren, inspired by the story, crowned their own May-queen.

“The May-Queen” by Mary D. Brine

"When I was little," said grandma Gray, "We used to welcome the month of May With a song and a dance on the village green, Choosing and crowning our May-day queen. We used to choose of the prettiest girls, The one who had the sunniest curls, The one who had the merriest eyes, As clear and bright as the May-day skies. "We made her throne of the daisies white, And of yellow buttercups, golden bright, And we twined gay blossoms about the hair Of our dear little queen so sweet and fair." So grandma said, and the children heard, And a loving thought in each heart was stirred; And they whispered together, and laughed in glee, "Dear grandmamma shall our May-queen be!" Then they brought the chair with the cushioned seat, And the cushioned footstool for grandma's feet, And led her merrily to the throne, And crowned her queen of their hearts alone. They twined the daisies and buttercups bright In the queen's soft hair so silvery white, And better than jewels or necklace rare, Were the clasping arms of those children fair. And the bees and butterflies hovered around; And the sunbeams danced all over the ground; And the birds sang merrily in the trees; And the breath of summer was in the breeze; And the delicate hue of the azure skies Seemed to lend new light to the loving eyes Of happy, dear old grandmamma Gray, Crowned by the children their "Queen of May."

Small Beginning

Poem Link. By George S. Burleigh.

I conclude this post with a small beginning. In a prior Around the Web post in March, I identified crocuses as a sign of spring. In this poem, George S. Burleigh did the same.

“Small Beginning” By George S. Burleigh

When the first little crocus peeped out of the ground,

And slyly looked round,

Not a flower was awake, not a big of new green

Was anywhere seen;

And it seemed with a shiver the little one said,

"Oh, I am afraid,

The trees are so naked, the earth is so black!

Please let me go back!

You have called me too early, my dear Mother Spring,

I am such a wee thing!"

Then a bluebird whistled, "Oh no! My dear,

It is good you are here;

For now we are sure that spring is near."

Then a sober old robin came bustling by

With the sleep in his eye;

"Ah, me! how stupid I was to wait;

And now I am late!

The bluebird has piped, and the crocus has come;

And you know by the hum

The hot little bee is beating his drum."

Then sweet Mother Spring, with a sunshine kiss,

Said something like this:

"Thanks, brave little crocus, so slender and small,

For heeding my call

While orchards were leafless, and snow-drifts staid

In the all-day shade:

You are telling us sweetly that soonest begun

The soonest is done;

That little by little makes up the great,

And early obeying is better than late."

Conclusion

The four issues of The Nursery that I studied were all quite good. The stories and poems are all of high quality and would, in my view, make terrific reading for children today. I only covered a small selection of the content, and I tried to choose a small theme for each of the four issues. Those who are interested may consult the original volumes on Project Gutenberg. As I noted at the top, Project Gutenberg currently hosts 48 issues of the magazine, all published from between 1873 and 1881, inclusive.