The June 4, 1895 edition of Harper’s Round Table covered the miniature backyard railroad system of Reverend H.L. Warneford of Windsor, England. Warneford used the back of his garden to construct a model rail system running 80 feet in length. His remarkably detailed model included two stations, advertisements, a variety of bridges, a signal tower, a snow-plow, and more. We are lucky that the Harper’s Round Table article is accompanied by six photographs of Reverend Warneford’s meticulous model. In this article, I will cover the 1895 piece on one of the most impressive rail system models one is likely to ever happen upon.

Who Was H.L. Warneford?

The article provides few details about Reverend Warneford other than that he was a clergyman who lived in Windsor, England, and that he had a remarkable faculty for constructing model trains and tracks.

Overview of Warneford’s Model Railway System

Warneford built the model railway system in the rear of his backyard garden. In so doing, he took aesthetic advantage of the rear of his garden being bordered by a brick wall.

Warneford’s model rail system ran from a station he named “Chicago” to a station called “Jericho.” In total, the track was 80 feet in length and had a gauge of 2-5/8 inches. We will discuss the rest of the model railway with reference to the photographs included in the original article.

The Chicago Station and the Skew Bridge

The below photograph shows the Chicago station and the skew bridge that began right after the train left the station:

Regarding the Chicago station, the article notes that it included advertisements and terminal facilities. While it is a bit difficult to make out in the photo, you can see both if you look closely.

The skew bridge is one of the many bridges that we will see in Reverend Warneford’s garden train station. This bridge is notable because the photograph shows that Warneford had practical reasons for building it in light of the topology of his garden. Harper’s credited Warneford with “overcoming the inconveniences of the ground which usually require the mechanical ability of railroad builders.”

Three Bridges of the Model Railway

As we noted, Reverend Warneford’s yard had uneven terrain. Like any good rail system builder, he did not let this stop him. Warneford constructed a variety of bridges to ensure the continuity of his 80-foot miniature railroad in his garden. One may be impressed to find that he used different kinds of bridges. I was more impressed to read that he chose to use different bridges at different points based on “which would naturally be best suited to the particular form or ravine or cavity over which the road is run.” His bridge choices were governed by practical considerations concerning his backyard terrain. Of course, they were.

Harper’s described the Warneford’s cantalever bridge, pictured below, as one of the prettiest in his garden. (Note: The original article uses “cantalever” instead of “cantilever,” so I will replicate the original form in this article.)

The magazine noted that the cantalever bridge was modeled after the Forth Bridge between England and Scotland.

You may note a tunnel on the far right of the cantalever bridge photo. What is on the other side of the tunnel? An American trestle bridge, pictured below.

When the train leaves Chicago, it crosses the skew bridge. It then rides over the American trestle bridge, through the tunnel, and then over the cantalever bridge. The train must then chug through a cutting and over one final bridge before reaching Jericho. That final bridge, pictured below, is the steel tubular bridge, pictured below.

Harper’s recommended comparing the bridges to the brick wall in three of the four pictures for an idea of their size. The bridges were small, but very intricately designed.

Signals and Other Features

Astute observers will notice that the train tracks were “fully equipped with sets of signals.” Lest one think that the signals were there for decoration, Harper’s revealed that they were worked with telegraph wires and posts. The signals worked, but that was not all they did:

“There are not only signals for connections and ordinary use, but Dr. Warneford has even constructed a fog-signal apparatus, which is worked by a spring when the engine passes over it, causing a hammer to fall on a small blank cartridge; and this, exploding, is the signal for the train to come to a stop at a time when, either on account of fog or similar impenetrable mist, the ordinary signals would be of no use.”

Let no one say that the good Reverend left anything to chance. As I will discuss below, he prepared his miniature train system to cope with even more severe conditions than fog.

The Snow-Plough

Snow is not foreign to Windsor, England.

Warneford’s model rail system was buried in snow during the winter of 1895. In fact, you may notice that snow featured in most of the images we have already posted. The reverend could have cleared the snow himself, but what fun would that be? Do giants regularly clear snow from life-sized rail systems? I think not. Behold, below, Reverend Warneford’s miniature snow-plough engine:

Harper’s noted that the miniature snow-plough had a difficult job trying to clear the miniature train tracks. It is unclear how successful the miniature snow-plough effort was, but few would have even thought to test it.

In the above picture, note the quarter-submerged signal tower toward the back-right of the image.

The Jericho Station

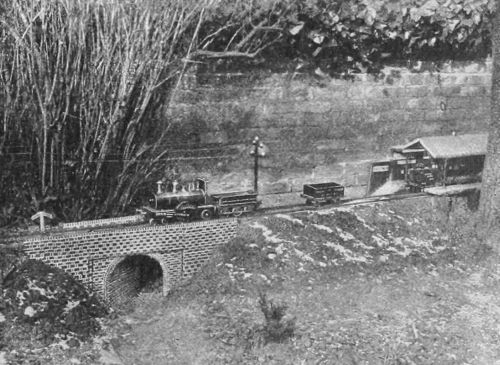

The train’s journey begins at Chicago and ends in Jericho after traversing four bridges, a tunnel, and occasional snowfall. Below, you will find a picture of the train entering Jericho Station.

The train’s arrival at Jericho would trigger a bell to signal that it had reached its destination. Harper’s keyed us into a button at the end of Jericho Station that triggered the bell. One observer who witnessed the train’s journey and noted the intricate signal towers opined that “the only thing that is lacking is the stentorian call of the conductor, ‘All tickets ready.’”

The Train

We have come a long way without discussing the train itself. Below, you will find an image of the train that I blew up (it is fuzzy for that reason):

Harper’s explained that the train was “a complete model of an ordinary English language.” In several of the pictures you will notice that the model steam engine produced steam. Harper’s explained that “the steam is generated by spirits…” The engine pulled along with it “a couple of trucks and a passenger-car.”

The article noted that one aspect of the train’s journey required some manual intervention from the Reverend:

“When the steam is up, and the train is started, the reverend gentleman has to run his level best to get to the next station before the train, otherwise it would be ‘missing.’”

The model train was good for exercise too.

The model train was “not more than eight inches long.” Harper’s noted that to produce a perfect model at that size must have involved remarkable care and attention to detail, but that Reverend Warneford proved that “such work is not impossible for anyone with a mechanical turn of mind.”

Other Notes on Materials

Parts of the train tracks in the images appear to be made of tiny bricks. According to Harper’s, however, those parts of the road were painted boards. While the Reverend did not use tiny bricks, his bridges were “sincere constructions in every part, watch ‘timber’ being set in place by itself, and the whole construction made to rely on its own strength, without any false support.” How strong were the bridges? According to Harper’s, the steel tubular bridge would “bear the weight of a small boy.” Similarly to the bridges, “[a]ll the castings for the wheels and machinery of the engines and cars are perfect in every way.”

Final Thoughts on the Warneford Model Railway

Harper’s concluded its article as follows:

“This whole railway, in fact, is a most interesting and suggestive piece of work, and it illustrates what mechanical ability and ingenuity can do, and how much amusement and profit even so busy a man as an English clergyman may find in working on such a thing as a hobby.”

Well said. Warneford’s railway was a remarkable piece of work, and his attention to detail was outstanding, allowing him to create an accurate railroad system model in a very small package. We are lucky to have six detailed images of his backyard rail system, although I wish we could also see it in action.