In this Around the Web post, I will explore the story behind an interesting way to say “I love you” in Japanese. As the story goes, Natsume Sōseki, a renowned Japanese novelist who lived from 1867 to 1916 and inspired countless writers who came after him, once translated the English phrase “I love you” into Japanese as “Tsuki ga kirei desune.” Tsuki ga kirei desu ne, can be translated into English in various ways, but the end result is something to the effect of “the moon is beautiful, isn’t it?” That is certainly a curious and elegantly lyrical way of confessing one’s feelings, perhaps peculiar to the Japanese language and sensibilities.

The “Tsuki ga kirei” story has gained currency on both sides of the Pacific. Curiously, however, there is no contemporaneous account of the story having happened, and no reference to it in any of Sōseki’s writings. Did the story happen at all? If Sōseki never translated “I love you” as a question about the beauty of the moon, where did the story come from?

Before beginning, I wish everyone a happy White Day. What is White Day? I offered a specious explanation in a humorous dialogue in February.

Update: I added the new Takashionary subsection to the article on February 20, 2024. I also changed the text for some of the article links to make them more descriptive. The article otherwise appears as it was originally published except where I note otherwise.

- A Note Before Beginning the Inquiry

- How I Learned About the Phrase “Tsuki ga Kirei”

- The Anecdote About Natsume Sōseki and Tsuki ga Kirei

- Alternative Version of the Sōseki Anecdote: “Tsuki ga tottemo aoi naa” (“The Moon is so blue tonight”)

- Is “Tsuki ga Kirei” Commonly Understood in Japan as Meaning “I Love You?”

- Did Nastume Sōseki Translate “I love you” as “Tsuki ga Kirei desu ne”?

- “Tsuki ga Kirei” Appears as a Love Confession in Other Media

- The American Origin of “The Moon is Beautiful” as a Confession (Humor)

- The Moon is Beautiful, Isn’t It?

A Note Before Beginning the Inquiry

In my article on fact checking reform, I took the position that it is important to square with readers from the outset in order that they know the methods and perspective of the fact checker. This is, to be clear, not a fact checking piece, but I figured that I ought to follow my own tangentially-related advice and carefully lay out the parameters of the instant inquiry.

To start, I do not know Japanese at all beyond a few common words and phrases. I am in no way qualified to provide any sort of Japanese translation. For that reason, I will rely on sources for any notes about the intricacies of Japanese.

Second, my purpose in writing this article is not to prove or disprove that the Sōseki anecdote actually happened. I do not think that finding a limited selection of English-language sources online – many of which clearly rely on similar accounts of the story – suffices for such a bold project. Thus, while my view from the evidence I gathered is that the story is likely a later invention, I am not writing the article for the purpose of definitively resolving the posited issue.

Third, as I alluded to above, I am relying exclusively on English-language sources gleaned from English language searches. I conducted various searches using the following search engines: DuckDuckGo, Startpage, Swisscows, Peekier, Mojeek, Yandex, Goo, Gibiru, Metager, and Elephind.

What follows is an inquiry borne of curiosity and an appreciation of aesthetics. While there is some fact-finding, that fact-finding is incidental to the primary considerations that prompted this project. Furthermore, as I noted, I will add some personal flourishes to the narrative.

Aside – “Moon” vs “moon”

Some sources capitalize “Moon” while others leave it lower case. This is a public service announcement. If we are referring to our Moon, “Moon” should be capitalized. Our Moon is a specific place – it deserves capitalization just as much as “Earth,” “Mars,” or “Pluto.”

If we are talking about moons as celestial bodies in the abstract, lower case is appropriate. But Earth’s Moon should always be capitalized. I presume that under the same logic, “Tsuki,” which refers to our Moon in Japanese, should also be capitalized.

Please note that I speak not from a high horse – I often forget to capitalize “Moon” when it should be capitalized in my own writing.

For the purpose of this article, I will reprint quotes as they appeared – meaning “Moon” will sometimes be lowercase. When I speak for myself, however, I will capitalize both “Moon” and “Tsuki” when referring to Earth’s Moon.

How I Learned About the Phrase “Tsuki ga Kirei”

Below, I will explain how I first learned about the phrase “Tsuki ga kirei” and became interested in its meaning.

2017 Anime Series: Tsuki ga Kirei

Tsuki ga Kirei on Crunchyroll.

Tsuki ga Kirei in my recommended anime series from 2011-2020.

An anime (Japanese cartoon) by the name of “Tsuki ga Kirei” aired from April 6 through June 29, 2017. It was simulcast in the United States by Crunchyroll when it aired in Japan. I thought it looked interesting, so I watched the first episode when it was made available for streaming by Crunchyroll.

Tsuki ga Kirei is an unusually low-key love story set in ninth grade. It is light on dialogue and drama, but heavy on careful attention to detail in depicting the little moments and subtle emotions of the cast – especially the two main characters. One, Kotarō Azumi, is a bookish aspiring author who is a bit shy and awkward and earns mediocre grades in school. The other, Akane Mizuno, is a top student and star of the track team, but who is also anxious and quite self-conscious. The story held up well for twelve episodes, and it is for that reason that I listed it third in my article of recommended anime of the decade from 2011 through 2020 for New Leaf Journal readers.

The purpose of this article, however, is not to review Tsuki ga Kirei anew, but rather to explain how the show led me to take an interest in the phrase “Tsuki ga kirei.”

“Tsuki ga Kirei” in Tsuki ga Kirei

Tsuki ga Kirei made sense as the name of the series in context. It is, as I noted, a subtle show, featuring two characters who struggle to express themselves. The name makes additional sense in light of the fact that one half of the main character duo, Kotarō, is an aspiring author and bibliophile.

(Note: The forthcoming content in the next subsection and this section alone discusses an important scene at the end of episode three out of twelve of Tsuki ga Kirei. I suppose that it could be construed as a very minor spoiler, but I limit my discussion to addressing only the portion of the scene involving the phrase “Tsuki ga kirei.” I do not reveal the ultimate resolution of the budding drama in the scene. While I think that it should have no effect on one’s enjoyment of the show, consider yourself warned if you would prefer to view the first three episodes without any foreknowledge.)

The Moon is Beautiful Scene

The characters in Tsuki ga Kirei do not expressly reference “Tsuki ga kirei” until the third episode. I believe that I became aware of the translation of the phrase before that, not to mention that Crunchyroll translates the title as “As the moon, so beautiful.”

In the third episode, Akane and Kotarō are sitting by a pond which reflects the moon. They are both unable to say anything because of their mutual shyness and awkwardness. Kotarō wonders to himself: “Who was it that translated ‘I love you’ as “Isn’t the moon beautiful tonight?’” He narrows it down to Osamu Dazai and Natsume Sōseki. Dazai is another renowned author who was active during the 1930s and 1940s, and one of his stories – the oppressively depressing Schoolgirl – features in the first episode of Tsuki ga Kirei.

Instead of wrestling with the question of which author reputedly came up with “Tsuki ga kirei,” Kotarō says to Akane ,“the moon,” while directing her attention upward. Akane is surprised, but then says “I know, it’s so pretty” with a smile, likely unaware of what Kotarō was getting at.

What happened next? I encourage you to watch for yourself if you are interested. This article, however, leaves the charming series on a cliffhanger.

The Anecdote About Natsume Sōseki and Tsuki ga Kirei

In this section, I will link to several articles that offer accounts of the story of Sōseki translating “I love you” into Japanese as “Tsuki ga kirei desune.” These accounts will also offer somewhat different takes on how “Tsuki ga kirei desune” is best understood in English. I will lead with the accounts that I think are the most interesting and authoritative, while offering a broad selection of English-language resources for you to read and consider.

Toru on Lang-8: “The Moon Is Beautiful, Isn’t It? (I Love You)”

Toru. Published on July 21, 2016.

Mr. Toru describes himself as a teacher at a university in Tokyo, Japan, and he has posted 1,781 entries on Lang-8. Since I assume that someone who teaches at a Japanese university in Tokyo is fluent in Japanese and familiar with Japanese culture, this seems as good a place to start as any. I add as an unrelated point that he has an amazing user icon on Lang-8. The smiling tree looks like something that I would draw were I to have just a tiny bit more talent. But I digress.

Mr. Toru’s post begins by noting that the phrase “tsuki ga kirei desune” “sometimes becomes a hot topic.” I assume by that he is referring to the authenticity of the account of the phrase’s origin and whether it actually constitutes a romantic confession. For the time being, let us set aside the “controversy” to consider his account of how the phrase was born and what it actually means.

Toru on the Literal Meaning of “Tsuki ga Kirei desune”

Mr. Toru states that the literal meaning of “tsuki ga kirei desune” is “the moon is beautiful, isn’t it?” That is the most common translation I saw before sitting down to research this article, for whatever that is worth. Mr. Toru adds that in addition to the phrase’s literal translation, it might embody the additional meaning of “I love you.”

Toru on the Sōseki Tsuki ga Kirei Anecdote

Mr. Toru reports that, as the story goes, Sōseki heard his student translate “I love you” from English into Japanese as “ware kimi o aisu.” He explains that “ware means I, kimi means you, and aisi means love). Thus, “I love you.” That is certainly a literal translation.

Mr. Toru recounts that Sōseki is reported to have responded: “Japanese people don’t use such an expression, you should say ‘the moon is beautiful isn’t it?’”

He adds that Sōseki’s view was that any Japanese person could understand the true meaning behind “tsuki ga kirei desune” as a profession of love even though none of the words translate to “I” or “love.” Mr. Toru notes that some think of the expression as “affectional, graceful, and beautiful.”

Toru’s Disclaimer on Confessing With “Tsuki ga Kirei Desune”

If you fall in love in Japan, are you safe using “Tsuki ga kirei desune” to confess your feelings to your beloved? Well, Mr. Toru is not so sure.

It might not actually convey the meaning of ‘I love you,’ please be careful.

Toru on saying “Tsuki ga kirei desune” to confess love in Japanese

I found Mr. Toru’s disclaimer interesting. In his post, he suggests that the Sōseki story is known to some extent in Japan. However, he adds that the “love confession” itself, “Tsuki ga kirei desune,” may not always convey “I love you” to all people. I think that he is most likely saying that while the Sōseki story is known in Japan, “Tsuki ga kirei desu ne” is not so ubiquitous that all Japanese people, or even most Japanese people, would understand it as a love confession. Perhaps many in Japan, if not most, would understand the confessor as stating that the moon is beautiful rather than stating that he or she is in love.

Indeed, the anime Tsuki ga Kirei provides a subtle example of this. Kotarō does not complete his indirect confession – halting at “the Moon…” Akane, after looking at the moon, smiles and agrees with him that the Moon is pretty. Nothing more. She clearly does not understand Kotarō’s reference to the Moon as a love confession, nor does it prompt her to confess her love for him. Had Akane thought that pointing out that the Moon was pretty could be seen as a love confession in that context, she would not have done so at that moment. It is worth recalling as an additional point that even the bookish Kotarō could not remember exactly which of two iconic Japanese authors the phrase was attributed to.

Yuri on Italki: “Confessing Your Love in Japanese”

By Yuri. December 16, 2016.

Ms. Yuri, like Mr. Toru, is fluent in both English and Japanese. She states unequivocally from the outset of her post that “tsuki ga kirei desu ne,” which she translates as “the Moon is beautiful, isn’t it?” means “I love you” in Japanese.

Her account of the Sōseki story is nearly identical to Mr. Toru’s in terms of the facts presented – including Sōseki’s specifically proposing “tsuki ga kirei desu ne” as a preferable translation of “I love you” to “ware kimi o aisu.”

Ms. Yuri offers some interesting information in explaining how a confession of love in the form of “tsuki ga kirei desu ne” would work in practice.

You can use this phrase with someone you like, while you’re under the moon. An appropriately literary response would be 死んでもいいわ | shindemo iiwa (I can die happy). This is the translated from the works of novelist Shimei Futabatei (1864-1909)

I actually knew this because my friend discovered the proper literary response to Tsuki ga kirei desu ne. I did not know that it derives from Shimei Futabatei. (Note: See my new 2024 addition to the article for a critical take against shindmo li wa being a proper response to tsuki ga kirei and the backstory of the former phrase.)

Ms. Yuri’s post suggests that Tsuki ga kirei desu ne may be more readily understood in Japan than Mr. Toru seems to believe. While I cannot resolve the disagreement, my overall impression leads me to guess that Mr. Toru may be closer to the mark on that point.

The post goes on to explain various ways that one can confess his or her love in Japanese, including a discussion of the most common confessions today. Because it is beyond the scope of the instant article, I will leave that for you to read – but it is interesting, especially for people who consume Japanese media.

Anton World: “Deto SP – Natsu Hito (2015) Aftertaste”

Anton World. Published on June 19, 2016.

To start, I must credit the author for choosing a pseudonym based on his adventures in the Tropico computer game series. For that reason, I shall refer to him as “El Presidente” in this article. A more in-depth explanation would be as far from this article as Mars, so let us not look beyond the Moon.

El Presidente describes a scene in “Deto – Koi to wa Donna Mono Kashira” – a live action Japanese drama. I do not watch live action Japanese dramas and had never heard of this series. So, I note from full disclosure from the outset that I am relying entirely on El Presidente for the description.

El Presidente describes in detail one character in the drama, Takumi, describing “Tsuki ga kirei desune” to the lady of his affections, Yoriko. I found this quite interesting in that it is an account of the phrase and the story behind it written for a contemporary Japanese audience.

El Presidente writes that Takumi relates to Yoriko that Sōseki was asked by a student how to translate “I love you” from English to Japanese. Sōseki, according to Takumi, explained to the student “that expressing [the] feeling of love directly to the object of affection is not compatible with Japanese culture…” For that reason, “it is better to express [love] indirectly by admiring the beauty of the moon…” After completing his explanation, Takumi repeatedly tells Yorko that “the moon is beautiful.”

This is a heavy-handed build-up to an ineffably subtle way of confessing love, but sweet, nonetheless.

Lingling Su on Medium: “Author Corner: Natsume Soseki”

By Lingling Su. September 17, 2019.

Su retells the story of the origin of “Tsuki ga kirei desune” in some detail – with Japanese included.

Mr. Su tells us that Sōseki was teaching English when a student asked him if his translation of “I love you” into Japanese was correct. The student translated “I love you” as ‘Ware Kimi wo Aisu,” close to a direct translation. In Mr. Su’s account, Sōseki replied that the translation was too direct for Japanese men, so no man in Japan would confess in that way. Sōseki suggested that a Japanese confession of love would be more elegant. As an example, he wrote the now-famous “Tsuki ga kirei desune.”

Interestingly, Mr. Su translates this differently than most other accounts I found. He states that “Tsuki ga kirei desune” should be translated as “the moon is beautiful having you beside [me] tonight.” According to Mr. Su, Sōseki opted for this indirect translation because as a man in the Meiji period, it was common to express a sentiment (Jou) rather than love directly (Ai) – an explanation that appeared in a 2013 article, discussed below.

Japan and the World: “Through Travelers’ Eyes: ‘Natsume Soseki’”

By Ayaka Ohara. August 2, 2013.

This website is edited by Caroline Hutchinson. Ms. Hutchinson describes it as showcasing the work of students taking a modern Japanese history course at the Kanda University of International Studies.

This specific post was authored by Ms. Ayaka Ohara.

Ms. Ohara writes of the origin of the phrase:

When [Natsume Sōseki] was a teacher, one day in class, he translated ‘I love you’ into “Tsuki ga Kirei desune’ which normally means ‘The moon is beautiful’ after he heard a student translate ‘I love you’ literally into ‘Ware Kimi wo Aisu’.

Why did Sōseki opt for such a lyrical and seemingly indirect translation? Ms. Ohara explained:

He said it was enough to communicate your feeling because he was a person in [the] Meiji period when feeling (Jou) was common [instead of] love (Ai).

It was for that reason, Ms. Ohara explains, that Sōseki found “the moon is beautiful” to be more in tune with Japanese sensibilities than a direct translation of “I love you.”

Ms. Ohara opines that it was natural for Sōseki to translate “I love you” in this way “because he was very smart, and he did not like unfashionable things.” She notes that his experiences as a man of the Meiji period in Japan were different than others, and this gave him unique ideas.

Ms. Ohara states that the phrase remains “favored among fashionable and intelligent people” and is still used today in Japan by those who find it more “tasteful” than a direct confession of love.

As we have noted, however, Ms. Ohara’s views of the phrase’s use in contemporary Japan is open to debate.

Yabai: “The Story of Natsume Soseki and The Stories He Had Written”

YABAI Writers. October 20, 2017.

Yabai does not include the details of the story wherein Sōseki is supposed to have corrected a student’s translation of “I love you.” It does, however, directly attribute “Tsuki ga Kirei” to Sōseki.

Among the many quotes by Natsume Soseki, ‘Tsugi ga Kirei’ stands as the most popular. The whole phrase is actually ‘tsugi ga kirei desu ne’, which means ‘the moon is beautiful, is it not?’ in English.

Why did Sōseki come up with such a phrase?

This phrase was used by Natsume Soseki as a form of saying “I love you”. For the writer, two people with deep feelings for each other do not need to use those three words to effectively convey their feelings. Sometimes, even the simplest phrases contain more emotion than direct ones.

I am not sure why Yabai uses “Tsugi” instead of “Tsuki.” I have always seen “Moon” written as “Tsuki” in English. Of course, translating Japanese words into English letters is an inexact science, so perhaps it is a variation of which I was hitherto unaware.

Alternative Version of the Sōseki Anecdote: “Tsuki ga tottemo aoi naa” (“The Moon is so blue tonight”)

While researching Tsuki ga kirei desu ne, I came across an alternative version of the phrase that is also attributed to Sōseki. “The Moon is so blue tonight.” This version of the phrase clearly refers to the same anecdote.

Below, I will discuss two sources which use “the Moon is so blue tonight” version of the Sōseki anecdote. Later in the article, I will link to some research which provides a likely explanation for why there are two versions of Sōseki’s supposed translation of “I love you.”

Durf.org: “Untranslatability”

By Peter Durfee. July 26, 2004.

This article is no longer live, but thanks to the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine, we can enjoy this interesting content from 2004. Mr. Durfee describes himself as “a translator and editor … at the Nippon Communications Foundation.”

In his post titled “Untranslatability,” he deals with phrases and words that are nearly impossible to succinctly translate out of their native language. In his post, he includes a variation of the phrase that we are translating today, as it appeared in Sato Kenji’s “More Animated than Life: A Critical Overview of Japanese Animated Films.” Mr. Durfee notes that he worked on the following passage article as an editor. The passage, reprinted from Mr. Durfee’s website, reads as follows:

Natsume Soseki once taught his students that the correct Japanese translation for ‘I love you’ is “Tsuki ga tottemo aoi naa’ (The moon is so blue tonight); what he meant was that to express within the Japanese cultural framework the same emotion expressed in English by ‘I love you,’ one must choose words like ‘The moon is so blue tonight.

“The Moon is so blue tonight.” That one is interesting. It seems to be less common than “Tsuki ga kirei.” Most of the references I found to the phrase refer to the exact same article passage that Mr. Durfee cited to. For example, see these posts at Lingualift and Stack Exchange. There is however one more recent example that cited to “the Moon is so blue tonight” without reference to Mr. Durfee’s article.

Anime News Network: “Japanese Fans, Official Translator Weigh in on Netflix Evangelion English Subtitle Debate”

By Kim Morrissy. June 27, 2019.

This example is interesting in that it appeared on Anime News Network, perhaps the largest anime news site in English, well after Tsuki ga Kirei aired. That is not to say that Tsuki ga Kirei popularized the Sōseki story – but I will venture that it was many potential readers’ first exposure to it. The article itself is about a “controversy” in whether a phrase from the anime Evangelion should have been translated as “like” or “love.” I will bypass the main subject of the article, and cut to the one reference somewhere near the middle that concerns us:

[T]he famous Japanese novelist Natsume Soseki is said to have taught his students: the ideal Japanese translation for ‘I love you’ is ‘Tsuki ga tottemo aoi naa’ (The moon is so blue tonight). ‘I love you’ may be too direct for a Japanese person to say aloud, even if the intent is implicit…

Mr. Morissy, himself a translator, does not opine on whether the Sōseki story actually happened or whether the phrase is a good translation of “I love you”. Instead, he takes a certain moral from the account, suggesting that the Sōseki story combined with the Evangelion debate in the article “suggests that perhaps English translators of Japanese texts should be more explicit in statements of romantic affection, depending on context.”

While Mr. Morrissy may have been relying on the same account, this article does serve as extra corroborating evidence that “the Moon is so blue tonight” is another credible version of the Sōseki story.

I suppose it is interesting – in different series, I have seen statements of romantic affection translated as both “I love” and “I like.” The distinction is already sometimes nebulous in English without having to translate from a foreign language. I wish the translators luck.

Is “Tsuki ga Kirei” Commonly Understood in Japan as Meaning “I Love You?”

Below, I will discuss an additional view on whether your average person in Japan would agree that “Tsuki ga kirei desu ne” conveys what “I love you” conveys in English.

Rei Miyasaka on Quora: Re; “Do many native Japanese agree with Soseki Natsume’s translation of ‘I love you’…”

By Rei Miyasaka. 2018.

(February 16, 2023 update: This excerpt came from a Quora question and answer. Unfortunately, the Quora page is not online and to the best of my knowledge, there is no archived version of it. Thus, while you can read my description of the question and answer, the source is no longer available.)

Mr. Miyasaka describes himself as a translator and editor.

He writes that he did not think that many people in Japan would consider “Tsuki ga kirei desu ne” a translation per se. Instead, Mr. Miyasaka believes that Sōseki was making a “rhetorical point” about how Japanese people expressed emotions. Mr. Miyasaka states that, as a general matter, “Japanese people love to euphemize and beat around the bush.”

Interestingly, Mr. Miyasaka opines that Sōseki’s translation would not have been seen as a direct translation of “I love you” even when Sōseki was supposed to have formulated it. In fact, were it an actual translation of “I love you,” “it would lose its sanctity and hence its value.” This makes sense – if the whole point of the “translation” was to say that Japanese people express their feelings indirectly, it would hardly make sense for “Tsuki ga kirei desu ne” to be understood in the same way as “I love you.”

Mr. Miyasaka sheds light on how “Tsuki ga kirei desu ne” may be understood in contemporary Japan. He writes : “I disagree with the common assessment among Japanese natives that there’s a generational difference in how we understand it.” He suggests that, while contemporary Japanese people do not understand “Tsuki ga kirei desu ne” as “I love you,” some believe that people in Sōseki’s time would have understood it that way. For his part, Mr. Miyasaka says “not so.”

Did Nastume Sōseki Translate “I love you” as “Tsuki ga Kirei desu ne”?

Having studied many accounts of the Sōseki story, we finally reach an important question – did the anecdote actually happen? Before sitting down to research for this article, I was aware that Sōseki himself never wrote anything to the effect of this translation and that the story was entirely anecdotal. For that reason, I was inclined to believe that the story was a later invention, much like how Socrates articulated many of Plato’s theories well after his death.

Several of the foregoing accounts vaguely alluded to there being a dispute whether Sōseki actually provided an unusual translation of “I love you,” but none addressed it squarely. I did, however, find a couple of accounts that looked into the story itself, and they more or less increased my confidence in my belief going in that Sōseki never corrected a student’s translation of “I love you” with “The Moon is beautiful, isn’t it?”

The Mainichi: “Edging Toward Japan: Is this really how you say ‘I love you’ in Japanese?”

Damian Flanagan. June 11, 2020.

Buried among forum posts, language-learning sites, and abandoned blogs was this article in the English-language version of The Mainichi, one of Japan’s longest-running daily newspapers. This article was also published in Japanese, so it was not written exclusively for an English audience.

The author, Mr. Flanagan, splits his time between Japan and Britain, has a Ph.D. in Japanese Literature from Kobe University, and is the author of “Nastume Soseki: Superstar of World Literature.” All in all, I suppose that we can count him as a credible source.

Mr. Flanagan Learns About the Sōseki Anecdote

Mr. Flanagan explains that on one occasion in a bar in Kyoto, a stranger asked him if he knew that Sōseki was said to have translated “I love you” from English as “The Moon is beautiful, isn’t it”? Mr. Flanagan, a renowned Sōseki scholar, had never come across that account while working in Japan, so he decided to investigate.

Mr. Flanagan found that the Sōseki story “is in wide currency in Japan.” He notes, however, that it did not appear in Sōseki’s books. “Was this episode buried in his complete works somewhere without my noticing?”

The Sōseki Story First Appeared in Writing in the 1970s

Mr. Flanagan investigated and found that Sōseki himself made no reference to the anecdote or “Tsuki ga kirei” in his many writings. Furthermore, while Sōseki died in 1918, “there [is no] written record of this anecdote before the 1970s…” Interestingly, however, Mr. Flanagan found evidence that the Sōseki anecdote already had some currency in Japan prior to its first appearing in written form in the 1970s.

Reconciling “The Moon is Beautiful” and “The Moon is Blue”

Mr. Flanagan was curious whether the Sōseki anecdote recounted something that had actually happened or whether it was an invention from the post-War period. In examining the issue, he provided the likely answer to a peculiarity I found earlier – that there are two versions of how Sōseki is supposed to have translated “I love you.”

“[I]n the 1950s there was a massively best-selling song called ‘Because the Moon is Blue Tonight,’ with the moon standing as a symbol for love. Did this somehow fuse into a little story about Soseki, first rendered as ‘The moon is blue night’ and then finally ‘The moon is beautiful tonight,’ gaining a gravitas as it went?”

Damian Flanagan

The fact that there are no contemporary sources that report that Sōseki translated “I love you” as “The Moon is so blue tonight” lend strong credence to Mr. Flanagan’s suggestion that the 1950s song played a role in the origin of the Sōseki anecdote. Furthermore, the fact that the anecdote did not appear until after the song became famous further supports the theory.

At the very least, we appear to have explained the less common version of the Sōseki anecdote, absent there being any evidence of which we are aware that the song “Because the Moon is Blue Tonight” was inspired by some earlier version of the Sōseki anecdote, as opposed to the contrary.

True or Not, the Anecdote Rings True to Mr. Flanagan

Despite the evidence that Mr. Flannigan describes suggesting that the Sōseki anecdote is a later invention, Mr. Flanagan nevertheless opines that the story “does somehow ring true.”

Soseki had little interest in translating the works of others because he felt it was antithetic to his own quest for individual expression. Yet he was extremely opinionated and knowledgeable about the art of translation itself, once famously correcting an entry in the English dictionary when his students at Matsuyama Middle School tried to catch him over its meaning.

Damian Flanagan

Sōseki, Mr. Flanagan writes, disagreed with Japanese scholars in his days translating words and phrases from English to Japanese in a direct way. For example, Sōseki opined that many scholars and writers translate things without regard to the fact that the references had no meaning to most Japanese readers. Yet, Mr. Flanagan writes, on the occasions when Sōseki himself included translated phrases in his writings, he did so in very clever ways. Mr. Flanagan states that the best example of Sōseki using a translation in his work comes from his 1908 novel, “Sanshiro.” Therein, two characters discuss the meaning of the English phrase “Pity’s akin to love,” from Aphra Behn’s “Oroonoko.”

One of the characters Yojiro mischievously offers a ‘crude’ translation [of ‘Pity’s akin to love’] – ‘Kawaisodata horetatte kotoyo’ which is virtually untranslatable back into English – along the lines that pitying someone can be the beginnings of falling in love with them.

Damian Flanagan

My Thoughts on Mr. Flanagan’s Findings

On the whole, Mr. Flanagan’s findings lead me to believe that the famed Sōseki “I love you” translation anecdote never happened. Furthermore, it seems likely, if not probable, that the anecdote itself had its origins in a popular 1950s song. However, Mr. Flanagan’s point that the story sounds plausible given Sōseki’s own views on translations likely contributed to its being accepted as true or possibly true by many in Japan.

With all that being said, it is possible that some later scholarly inquiry could discover some link between the story that was first printed in the 1970s and something that Sōseki actually said, even if that may be unlikely given the fact that Sōseki has been the subject of an immense amount of scholarship.

Takashi’s Japanese Dictionary: “Why ‘The moon is beautiful, isn’t it?’ Could Mean ‘I love You’ in Japanese

Takashi. April 30, 2020.

Note: I added this section to the article on February 20, 2024.

Takashi of the “Takashionary” describes himself as a native Japanese speaker who “introduces intriguing, quirky, and userful Japanese expressions.” Although this article was apparently published before my tsuki ga kirei essay, I did not come across it while conducting my original research back in 2021. However, it is more than interesting enough to add as an addendum to my original post.

Takashi reached the same conclusion as I did based on my sources that there is no record of Sōseki ever having translated I love you as tsuki ga kirei desu ne. He linked to a Japanese source which he reports came up with similar information to what I found in English sources.

Takashionary includes two interesting notes beyond agreeing that the tsuki ga kirei story is likely a post-Sōseki invention.

Firstly, Takashionary makes clear that “the poetic meaning of [tsuki ga kirei desu ne] is recognized only among those who love Japanese slang or trivia. He opined that many Japanese people would thus not recognize tsuki ga kirei desu ne as a love confession. My original sources were somewhat mixed on how well-known the story is in Japan, but this take was in line with the overall tenor of my findings (I wonder if the Tsuki ga Kirei anime was popular enough to shift the balance at all).

Secondly, Takashionary takes the position that there is no proper response to tsuki ga kirei desu ne and that reports that the proper response is shindmo il wa are false. He reasoned that shindmo li wa, which translates to I can die happy, was a phrase created by Shimei Futabei and had nothing to do with Sōseki. Only one of my original sources (a Japanese woman writing on a translation forum) connected shindmo li wa to tsuki ga kirei, but to be fair, she did note that the source of the quote was Futabei . Takashionary went a step further and explained that Futabei’s shindmo li wa was actually a translation of a Russian word, bama. In an additional note, he states that there is disagreement over whether shndmo li wa is a good translation of bama.

While Takashionary rejects the idea that there is a proper response to tsuki ga kirei, Takashi suggests three possible responses (note that “it” is the Moon in all of the suggestions). First, we have a “witty and unrealsitic” positive response to the confession: “Yes, I wish I could watch it with you for good.” Second, we have a witty and unrealistic negative response: “(You) may think so because (you) can’t touch it.” Finally, Takashi offers a “realistic” response wherein the recipient of the indirect love confession takes the statement about the Moon’s beauty literally: “Yep. By the way, you said you had something important to tell me, right? What is it?” Without spoiling where, I will note that I have seen a version of response three in media.

Eiji Takano on Quora: Re; “Why does “The Moon is beautiful” (Tsuki ga kirei desu ne) mean “I love you” in Japanese?”

By Eiji Takano. 2018.

According to his biography, Mr. Takano was born in Japan in 1942 and worked for many years as a camera man for NHK-TV, public television in Japan. In 1995, he moved to Mississippi after marrying an American.

Mr. Takano takes the most decisive view of all of our sources that the Sōseki anecdote wherein he translated “I love you” as “Tsuki ga kirei desu ne” never occurred. He notes that there is no original source for the story, “so this is an anecdote someone made up.”

Why do many people believe the anecdote? Mr. Takano thinks that this is because of what people understand about Japanese society in the time of Sōseki: “Soseki Natsume was born in the last year of the Edo era (Samurai era). So, the society was still stoic and even lovers couldn’t walk hand in hand in public. This historical context makes this anecdote believable.”

But despite its being “believable,” Mr. Takano does not believe it. In his view, a younger generation of writers were responsible for spreading the story. He offered a humorous take on it:

At first it was half jokey. Then it became a code: ‘I love you.’ To decipher the code, you have to know [Sōseki] Natsume’s story. If you don’t, the message goes to the sea like a North Korea[n] missile and sink[s] in vain.

Eiji Takano on Quora

My Thoughts (Humor)

Once upon a time, a student asked Natsume Sōseki how to translate “this person is too dense to understand my confession of love” from English to Japanese. She tried to translate it directly, but Sōseki was unimpressed.

“The Japanese are a subtle people,” he explained. “We would not say in such a direct way that someone was too dense to understand a lyrical confession of love.” Sōseki offered a more poetic translation.

Dear leader launched a missile that fell haplessly into the Sea of Japan, sinking in vain.

(I could not find the original Japanese, so you will have to bear with my attempt to convey this beautiful anecdote in English.)

The young lady had but two questions. “North Korea?” “Dear leader?”

Later, she went on to write a lite novel series titled “I Cannot Believe That This Boy Is So Dense and Cannot Understand Any of My Point-Blank Confessions.” She had to add a few words for it to be long enough to be a proper lite novel title.

“Tsuki ga Kirei” Appears as a Love Confession in Other Media

Now that we have examined the various Tsuki ga kirei anecdotes and considered whether the underlying story ever happened at all, let us look at a few additional examples wherein the phrase appeared in media.

January 7, 2025 Update: I published an article about the appearance of the phrase in a 2024 episode of the Shangri-la Frontier anime.

IT’S BECCA: “The Moon is Beautiful”

By Becca. May 17, 2019.

Ms. Becca’s article as about a Korean drama called “Romance is a Bonus Book.” I know even less about Korean dramas than I do about Japanese live action dramas, and I have thus unsurprisingly not heard of “Romance is a Bonus Book.” Ms. Becca provides plenty of information about it for those who are interested.

In her blog post, Ms. Becca includes the following quote from a character – Eun-ho – in an episode of “Romance is a Bonus Book”:

Instead of ‘I love you,’ Soseki Natsume said, ‘The moon is beautiful.’ It was a night that made me think of him.

Eun-ho from “Romance is a Bonus Book,” quoted by Becca of “IT’S BECCA”

Ms. Becca, like me, did some research into the phrase and found conflicting accounts on whether Sōseki ever said it. Her account is interesting in that it is an example of the phrase appearing in South Korean media. I do not know, however, whether the Sōseki story has any currency in South Korea generally.

Polygon: “Persona 4 Golden guide: All classroom answers”

By Jeff Ramos. June 13, 2020.

I have covered Persona 4 Golden in several articles on site. For example, I discussed a heartwarming family scene from the game last June and have thus far reviewed two Persona 4 artbooks. In the first post, I noted that Persona 4 combines traditional dungeon-crawling and turn-based combat with living the daily life of a high school student. Life as a student would not be complete without having to answer questions in class. Persona 4 contains numerous in-class questions, and if the player answers correctly, he or she receives a stat bonus that helps him or her make friends.

That is right, being smart has rewards.

For those who cannot be bothered to pay attention to brief video game lectures or who do not know the answers from their real-life experience, there are many guides offering all the answers to Persona 4 questions.

The May 7 in-game question asks the player: “Do you know how Soseki Natsume translated the English phrase ‘I love you’ into Japanese?”

Those of you who read this article should be able to answer that without relying on online guides.

The question reappears in an in-game midterm, so you will do well in Persona 4 to remember it.

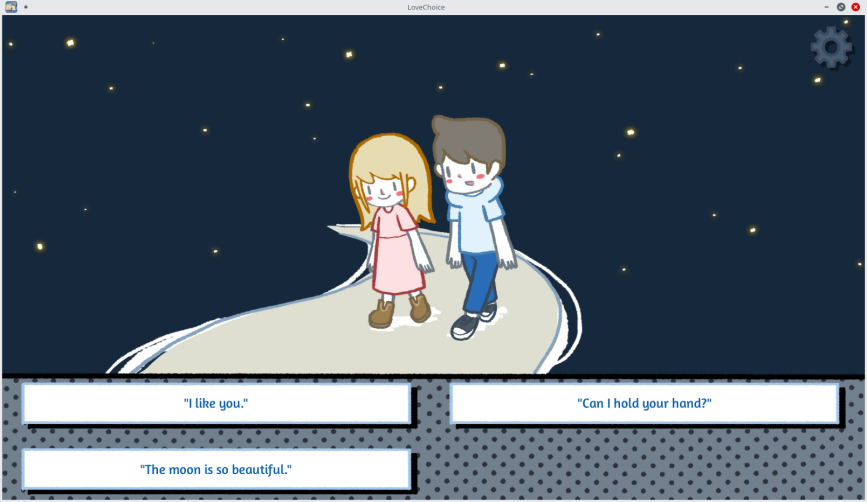

Video Game on Steam: LoveChoice

I reviewed LoveChoice, a visual novel available for Steam, here on site. LoveChoice is a Chinese visual novel, so I suppose a reference to the moon in the context of a confession of love counts as an international example.

To be clear, I am not sure if the phrase here is analogous to Tsuki ga kirei in the original, untranslated version of the game. But the dialogue choice, pictured above, in conjunction with the context of the scene, made it worth including.To be clear, I am not sure if the phrase here is analogous to Tsuki ga kirei in the original, untranslated version of the game. But the dialogue choice, pictured above, in conjunction with the context of the scene, made it worth including.

I respectfully decline to spoil the best way to handle the scene in the game.

The New Leaf Journal: “Welcome to The Emu Café“

By Nicholas A. Ferrell. May 16, 2020.

Well before I got around to writing an article on “tsuki ga kirei,” I snuck a modified version of the English translation of the phrase into my introduction to our Emu Café section.

Lovers of elegance and wisdom are all in accord that the Moon, embroidered in the starlight curtains, as seen through The Emu Café’s window, is indeed beautiful.

Nicholas A. Ferrell

My colleague, Victor V. Gurbo, wrote in his terrific article about his original song, Mondrian: “As a general rule, I disfavor musicians explaining their own work.” I do not share his well-reasoned reservations, at least with regard to my writing, so I will offer the definitive interpretation of my sentence.

The foregoing passage relies on the interpretation of “Tsuki ga kirei” as expressing one’s feelings by sharing an object of affection. Two hearts united in admiring something beautiful can be two hearts united. “Lovers of beauty and wisdom” who discourse about “aesthetics and the life lived well” in The Emu Café agree that the Moon is beautiful precisely because they love beauty and wisdom. If two people can agree that the Moon is beautiful, they can have a pleasant and meaningful conversation in The Emu Café.

The American Origin of “The Moon is Beautiful” as a Confession (Humor)

Let us conclude with a bit of history. In the midst of my research – I made a shocking discovery. Not only was Sōseki not responsible for “the Moon is beautiful” love confession, but its origin is English. Do I have proof? See below.

Crawfordsville Weekly Journal

By (and probably paid for by) P.R. Simpson’s. Published on July 24, 1873.

On second thought, perhaps that is just an advertisement for P.R. Simpson’s. There is a good moral here, however. Kids should not be out too late. School and all.

The Moon is Beautiful, Isn’t It?

I hope you enjoyed my somewhat comprehensive look at the English-language sources on the phrase “Tsuki ga kirei desu ne?” and the anecdote behind it. Regardless of whether Sōseki himself ever translated “I love you” with an appeal to the beauty of the Moon, it is a beautiful phrase and sentiment – and one can see why it gained currency despite its uncertain origins. There is merit to lyrical subtlety, in expressing things in an aesthetic, indirect way. However, I would caution those who prioritize clearly conveying their feelings to be careful about using “Tsuki ga kirei,” lest their confession fall into the sea like a missile launched from a North Korean testing site.

If we have any readers who speak Japanese or have some additional insights into the Sōseki anecdote, I welcome your feedback (see contact page). This article need not put all the questions to rest.

Here’s our first post to kick off the theme week Expressions of Love in Different Cultures!

There’s a story, which probably many of you have heard before, about Japanese author Natsume Sōseki and his…

Can anyone be more dutiful;

If I were to say,

‘The moon is beautiful’

You’d agree without a seconds delay,

For yours is a pure soul

And…