I came across an incisive blog post by Mr. Matthew Morgan on his personal blog titled The Deception of ‘Buying’ Digital Movies (archived). The article is of particular interest to me because I have covered how digital media sales are effectively indefinite rentals, most directly in my July 2022 article, Digital Purchases as Indefinite Rentals. However, in that post and in other posts that touched on the issue, such as my article about DRM-free games on Steam and my piece on lessons from Google’s shutting down its Stadia service, I addressed the issues with reference to my concept piece on the digital home. Mr. Morgan attacked the issue from a different, perhaps more immediately practical angle: deceptive marketing.

Digital “Purchases” On Amazon

Mr. Morgan used as his example movie purchases on Amazon. His test case was a 2014 movie called Hercules (I assume this is about the Greek mythological hero, but my movie knowledge is somewhat lacking). According to Mr. Morgan (I will take his word for it since I have never streamed a movie on Amazon), there are three ways to stream Hercules. First, one could subscribe for a streaming service on top of his or her Amazon Prime subscription for 4.49 pounds per month. (Requiring a purchase on top of a subscription invokes the Stadia fiasco.) Secondly, the Amazon customer could rent the movie for a 48 hour period for 3.49 pounds, wherein the 48 hour period begins when the individual watches the movie for the first time, so long as it occurs within 30 days of the rental purchase. Finally, the individual could buy the movie for 9.99 pounds.

Mr. Morgan focused on the third option, the purchase option. Specifically, Mr. Morgan argued that the “‘Buy’ button is a scam.” He quoted from the Amazon Prime Video Terms of Use:

Purchased Digital Content will generally continue to be available to you for download or streaming from the Service, as applicable, but may become unavailable due to potential content provider licensing restrictions or for other reasons, and Amazon will not be liable to you if Purchased Digital Content becomes unavailable for further download or streaming.

In short, you will be able to watch the digital movie which you purchased on Amazon as long as Amazon decides to make the video available. Note that Amazon’s Terms provide that not only may a video be removed because the video license-holder decides to take it off Amazon, but also for other reasons, which suggests that Amazon may take a video down on its own initiative as well. Amazon is of course insulated from any disability from removing a purchased video from one of its customer’s libraries, per its terms of use. Were one to purchase a movie only to see it removed soon after purchasing, his or her only hope of redress would be to rely on the benevolence of Amazon’s customer service team.

Mr. Morgan focused primarily on the possibility that the video rights holder may remove the video in explaining that “Amazon is allowed to ‘sell’ you a movie where they don’t have a perpetual and irrevocable license to the movie they are selling.” This is quite true, well-placed quotation marks and all, and as I noted, it appears that Amazon may remove purchased movies even in cases where it is not demanded by the rights holder. We need not pick on Amazon exclusively, however. Mr. Morgan noted correctly that the same situation exists with other online storefronts, including iTunes. He noted a single good exception in the sea of digital “purchases“: GOG, which is primarily a DRM-free game retailer, apparently sells a small selection of DRM-free movies.

Digital “Purchases” Generally

Mr. Morgan contrasted the disposition of digital purchases with physical purchases, which I did similarly in an article praising Nintendo for continuing to prioritize physical game media. To be sure, there are restrictions on how one can use physical media (e.g., movies, games) – most readers should be familiar with the FBI notices on movies. But those restrictions come far short of resulting in the loss of those purchases all together:

If you buy a DVD or a Blue-Ray at a retail store, you are able to play that disk for as long as that disk physically works (often over 20 years). There are very few if any countries that would allow a shop to send around bailiffs to seize DVDs already bought years past, because the distributor no-longer has the rights to distribute the content.

This is true, and it cuts to the fundamental difference between modes of distributing physical media and the dominant (albeit not exclusive) mode of distributing digital media.

Solutions

Having highlighted problems with the current digital purchasing scheme, we ought to look for solutions or, if not solutions, the proper ways of understanding the current environment.

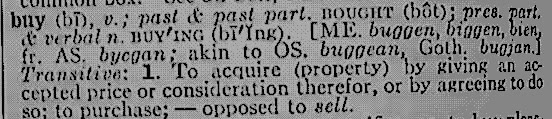

Firstly, I agree fully with Mr. Morgan that Amazon and many other retailers are engaging in deceptive marketing by using the term “buy” for what is plainly a rental for an undefined period – specifically with respect to the movie example which he provided. The term buy, in its ordinary meaning, entails ownership. See, for example, the definition from my 1952 edition of Webster’s Second:

To acquire (property) by giving an accepted price or consideration therefor, or by agreeing to do so; to purchase – opposed to sell.

Amazon expressly places the “buy” option as an alternative to “rent.” Renting, of course, entails paying for the enjoyment of something for a certain period, which may or may not be renewable depending on the terms of the rental agreement.

Amazon technically details the limitations on the “buy” option in its Terms of Service. However, one will find that the explanation is rather deep in a document that ordinary Amazon customers will not read. No matter how much hand waving one does, the effect of Amazon’s framing of the “rent” and “buy” options will have the effect of surprising unsuspecting customers when one of their purchases disappears from their library.

As an initial matter, we can resolve this issue by demanding more transparency and honest marketing. While I, like Mr. Morgan, prefer digital purchases that I actually own, such as all of the products sold by GOG or DRM-free games on Steam, a fair compromise is insisting that storefronts which adopt alternative ways of doing business should be forthright. “Buying” Hercules from the Amazon digital movie store is clearly not the same as “buying” a DVD or Blu-Ray of the same movie from Amazon.

Using the example articulated by Mr. Morgan, I have a few suggestions. Firstly, I would recommend not using the term “buy” in contrast to “rent” – because it is plain from Amazon’s terms of service that there are severe limitations on buying. Moreover, Amazon should, on the same page as the “buy” option (or whatever it would be called in the alternative), make the limitations on purchases readily accessible. I will go far as to suggest that in order to make it clear without harming Amazon’s own business interests, Amazon could also provide a link to the corresponding physical media for the movie, if such physical media exists and is available on Amazon, to provide prospective customers with an alternative means of giving Amazon money for the movie.

Mr. Morgan’s most incisive note in his article concerned Amazon’s presuming to sell digital media that it does not have a perpetual license to. This is a very interesting point. Were Amazon to want to be more ethical to its customers, it would make clear on the store page for a given movie the nature of its own rights to distribute and stream the movie . For example, in the case of Hercules, it appears that Amazon itself does not have a perpetual license to stream the movie. That is, Amazon’s own rights to the movie can be revoked by the license-holder. If this is the case, how can Amazon sell the movie? However, this is not the case with everything streamed on Amazon. As I understand it (correct me if I am wrong), Amazon itself is also a producer, meaning it likely does offer content that it does own perpetual rights to. It would make sense for Amazon to be transparent about its own rights to media it offers for streaming and to distinguish its terms of service based on those rights. This recommendation is similar to my request that Valve (the company behind Steam) clearly note the DRM-status and launcher requirements of digital games in its store.

Finally, Amazon absolutely must be more clear about the scenarios in which it can remove purchased digital content from its customers’ libraries. The case in which the license holder revokes Amazon’s rights to offer the content is clear. The “other reasons” provision in its Terms of Service is not at all clear. What are these other reasons? Can Amazon remove purchased media on a whim? Does it remove purchased media because its current executive leadership disagrees with it? Would Amazon remove purchased media if government officials lean on it to do so? Does Amazon consider its streaming of a new version of a movie or TV series to be a reason to remove the old version? Transparency for purchasers would be welcome.

(To be clear again, this point is not exclusively about Amazon, but Amazon, like Steam in the gaming area, serves as a good example because of its size and significance in the area of content streaming.)

Finally, the most important thing is for consumers to have a solid understanding of purchases in the current digital sphere. No matter how much we may want Amazon or any other major digital seller to change how it does business, business is unlikely to change in the immediate future. Intelligent and thoughtful consumers can consider how different sellers do business, their own interests in a particular product, and whether alternatives are available.

For example, in the case of Amazon, it is worth considering with respect to a movie what your purpose is in buying or renting it. If this is a movie that you want to keep in perpetuity, purchasing physical media is clearly preferable to purchasing or renting it in digital form. If the ability to view the movie long term is not as important to you, the question is whether to buy or rent the digital version. If it is likely the case that the movie will only be watched once, renting would seem to be the preferred option. Buying the movie in digital form only makes sense if (A) the movie is not important enough to own in a physical format , and (B) one is likely to watch the movie at least three times. With respect to a purchase, to the extent that a customer has a long-term interest in being able to watch the movie, he or she should examine, prior to making a digital purchase, whether the rights holder (if not Amazon) has previously removed its content from Amazon or other streaming services, or whether there is anything about the movie or TV show which may make it vulnerable to removal for other reasons. The same reasoning applies to other digital storefronts.

I conclude by noting that while I prefer a system which allows people to own their digital purchases, my position is not against all forms of streaming or rental. I have previously noted that I subscribe to two anime streaming services which I use to watch new officially licensed anime series as they come out. In the event I very much like a series, I can purchase it in physical form since it is not uncommon for the major anime streaming services to lose rights to series. However, in that case, it is clearly understood what one is paying for in the streaming service. I also own games on Steam, many of which fall into the indefinite rental category (Steam has a fairly good reputation in this area, however). Finally, I have books in my Kindle library that are, by definition, indefinite rentals.

Allowing people to own their digital purchases with, at a minimum, the same legal limitations that would apply to physical purchases of the same, empowers consumers relative to the current dominant digital media regime. However, short of that ideal, information also empowers consumers. When retailers are forthright and honest about what digital media purchases and rentals are in practice, consumers have the ability to make informed decisions about how they spend their money to engage with digital books, games, and movies, or in the alternative to purchase physical versions thereof. We should demand that transparency at a minimum while simultaneously promoting better, pro-consumer means of digital content distribution (and physical content distribution as an alternative) that also takes into account the equities of the rights holders.